Simple Life

My November Song

A prayer of gratitude for the lives that touch us and those that await beyond

By Jim Dodson

On one of the last warm mornings of summer, I was watering shrubs when I heard a heavy thump behind me in the garden. Turning around, I saw only half a dozen birds feeding at the three feeders that hang from our aged maple’s outstretched limbs. I walked over to investigate.

I found a large squirrel crawling desperately on the ground toward one of the young azaleas planted back in the spring. The critter had evidently fallen from one of the high branches and was either dazed or severely injured. As I approached, the big squirrel curled up at the base of the plant and burrowed its nose under the shrub’s branches.

My first impulse was to fetch a garden tool and end the poor animal’s suffering. But long ago I made a pact with the universe to cause as little harm as possible to creatures large and small, probably the result of reading too many transcendental poets and Eastern sages early in life, and covering a great deal of murder and social mayhem during the first decade of my journalism career.

To my wife’s amusement (and sometimes horror), I’ve been known to gently escort spiders and captured houseflies to the door, return snakes to the wild and even grant the odd mosquito a reprieve to live and bother someone else another day.

Not counting the untold number of innocent garden plants I’ve inadvertently offed due to general ignorance or untimely negligence, I’ve generally abided by the naturalist maxim that it’s best to let nature take care of her own. So for this reason I went back to watering the shrubs for a spell, hoping the big fallen fellow was merely stunned.

Our little patch of paradise is a remarkably peaceful kingdom. Dozens of birds feed daily from three large feeders that hang from the old maple’s mighty limbs — a perpetual challenge to the squirrels that inhabit the forest of trees around us.

Over the years, they’ve displayed impressive acrobatic skills and inventive ways to get at those feeders, prompting me to constantly come up with strategies to thwart their efforts. It’s kind of a fun game we play. Fortunately for them, the birds are absurdly sloppy eaters, accounting for considerable spillage on the ground that keeps both squirrels and young rabbits rather well fed. That’s the silent bargain we make to keep our little kingdom in natural balance.

When I walked back to check on the fallen squirrel, however, he was lying right where I left him, perfectly still. He was dead.

I picked him up to look him over. He was an older fella bearing scars, nicked-up by life. Perhaps he’d simply lost his grip or just let go. It was impossible to know. In any case, it seemed only fitting to bury him on the spot where he lived out his final moments on this Earth — underneath the young azalea.

It was my second death of the week.

Two days before, on a beautiful morning when the rains I’d been waiting and praying for all summer finally arrived, we decided to put my beloved dog, Mulligan, to sleep.

Mully, as I call her, found me 17 years ago, a wild black pup running free just above the South Carolina state line, literally jumping into my arms as if she’d been waiting for me to come along. She was my faithful traveling companion for almost two decades, even journeying along most of the Great Wagon Road for my latest book project.

Three days before we lost her, Mully made the daily mile-long early morning walk we’ve strolled together for over a decade. Never sick a day in her life, it was the rear legs of this gentle, soulful, brown-eyed border collie I called my “God Dog” that finally gave out. She hobbled painfully on three legs around the Asian garden she watched me complete this summer, and settled at my feet where we sat together on a bench most evenings just watching the world. Her upward gaze told me it was time for her to go.

It was the hardest — but right — thing to do.

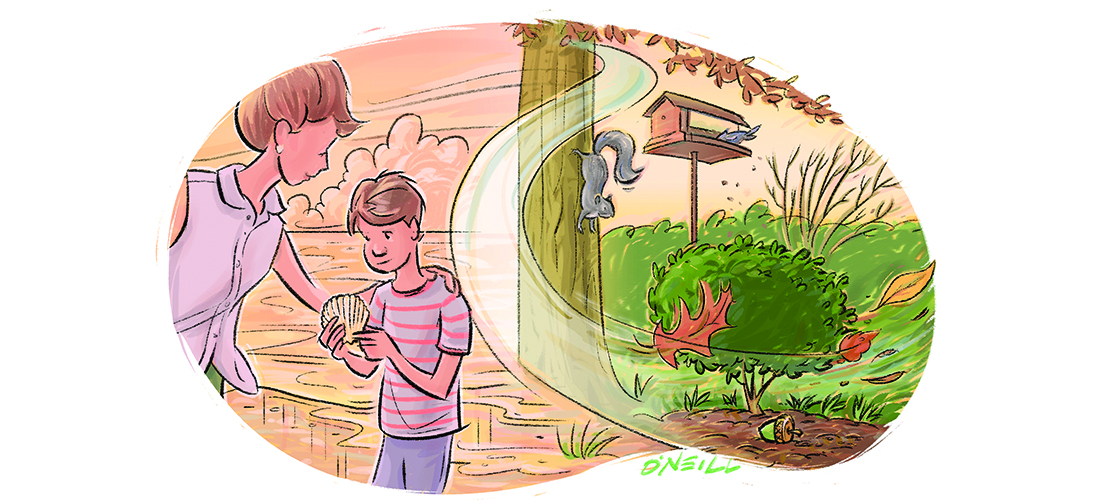

The idea of the afterlife for all God’s creatures — especially dogs — has fascinated me since I was a little kid. One of my first memories of life comes from a late autumn evening in 1958 when my mother and I were walking the empty beach at low tide near our cottage in Gulfport, Mississippi, looking for interesting seashells washed up from the Gulf of Mexico. November storms famously coughed up a bounty of unusual shells along the shore. It was my first lesson in immortality.

Our dog, Amber, had just died of old age. I was sad to think I would never see her again, and wondered what happens when dogs and people died.

My mom picked up a perfect scalloped shell, pure alabaster white, and handed it to me.

“Tell me what you see in that shell,” she said.

“Nothing. It’s empty.”

She explained it had once been the beautiful home of a living creature that no longer needed it, leaving its protective shell behind for us to find.

“Where did it go?” I demanded.

“Wherever sea creatures go after this life.”

“Do you mean heaven?”

She nodded and smiled. I’ve never forgotten her words.

“That’s where your dreams come true, buddy.”

“Same with Amber?”

“Same with Amber.”

A few years later, a marvelous Black woman named Miss Jesse came to help heal my mom after a terrible late-term miscarriage that nearly killed her. I often pestered Miss Jesse in the kitchen or when she took me along to the Piggly Wiggly. One evening I asked her why all living things had to die. She was rolling out dough and making biscuits at the time.

Her rolling pin kept working. “Let me ask you something, child,” she said matter-of-factly. “Do you remember a time when you weren’t alive?”

I could not.

“That’s because you ain’t never not been alive, baby. Nothin’ you love dies. It just passes on to a new life — just like the trees in spring.”

Half a century later, I heard the voices of both my mother and Miss Jesse in a powerful song called “Take it With Me” by Bluesman extraordinaire Tom Waits.

I played it the day Mully left me. I’ll play it again when I spread her ashes in the garden she helped me create.

I play it, in fact, every year when the leaves begin to fall. It’s my November song.

The children are playing at the end of the day

Strangers are singing on our lawn

There’s got to be more than flesh and bone

All that you’ve loved is all you own…

Ain’t no good thing ever dies

I’m gonna take it with me when I go

Due to summer’s extremely dry conditions in our small corner of paradise, the leaves fell early this year.

By the time we give thanks for this year’s tender mercies, missing friends, beloved traveling companions and even fallen squirrels that have graced our lives with their presence, they may all be safely gathered up to wait for us. OH

Somewhere where dreams come true.

Jim Dodson is the founding editor of O.Henry.

Alamanc

November is a great sweeping wind, a clearing of what must go, a dance with a howling reaper.

The crickets have disappeared. Their nightly serenades, which crackled like warm vinyl from spring through harvest season, faded with the first hard frost. In their wake, the wind shrieks through naked trees. A great horned owl bellows from his perch.

The garden folds into itself. The porch toads that lurked by the watering can on warm autumn evenings now burrow beneath the frost line. Field mice shimmy down chimneys, squeeze through eaves, craft their nests inside cozy walls.

Songbirds come and go. Hermit thrushes strip the hollies of their crimson fruit. White-throated sparrows shuffle through crumpled leaves, scratching up what’s buried underneath.

The wind sings of a quickening darkness. The squirrels, scrambling to cache pecans as they fall, retort with squawks and chatter. A skein of geese sails across a golden sunset.

At dusk, when the wind nips at the heels of those still roaming, a pair of coyotes yips and howls beyond the fringe. Back and forth they shriek, wailing like banshees, piercing the air with their shrill and haunting staccato.

“I’m here,” cries one to the other.

A single voice sounds like dozens.

A biting wind howls back.

When Pies Fly

For our neighbors in Albany, Georgia (pecan capital of the world), it’s raining you-know-what right now. But we have our share of toothsome treasures plummeting upon our leaf-littered neck of the woods, too. Especially in the southeastern part of the state. Whatever you call them — PEE-cans or pee-KAHNS — ’tis harvest season. Pick them as they drop or else the crows and squirrels will beat you to it. You’ll want to let them cure (essential if they’re not yet ripe) before shelling and freezing them. Store them in a mesh bag — and in a cool, dry place — for about two weeks. While you’re waiting? Dream of pie.

On that nut-studded note, have you ever cracked pecans? If so, then you can more deeply appreciate that the average pecan pie packs between 70 and 80 of those sweet and buttery little candies. No need to mention the calories.

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being.

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing

— Percy Bysshe Shelley

Prepare to be Dazzled

On Tuesday, Nov. 8, a total lunar eclipse begins around 3 a.m. According to Smithsonian magazine, which named this celestial event one of 10 “dazzling” must-sees of 2022, the moon will appear reddish, as if “all the world’s sunrises and sunsets” are being cast upon it.

Speaking of dazzling events, here’s to hoping your Thanksgiving will be described as such. At the very least, don’t let the parsnips eclipse that homemade pie. OH

Remembering Frank Jr.

A tribute to a leader

By Jim Jenkins

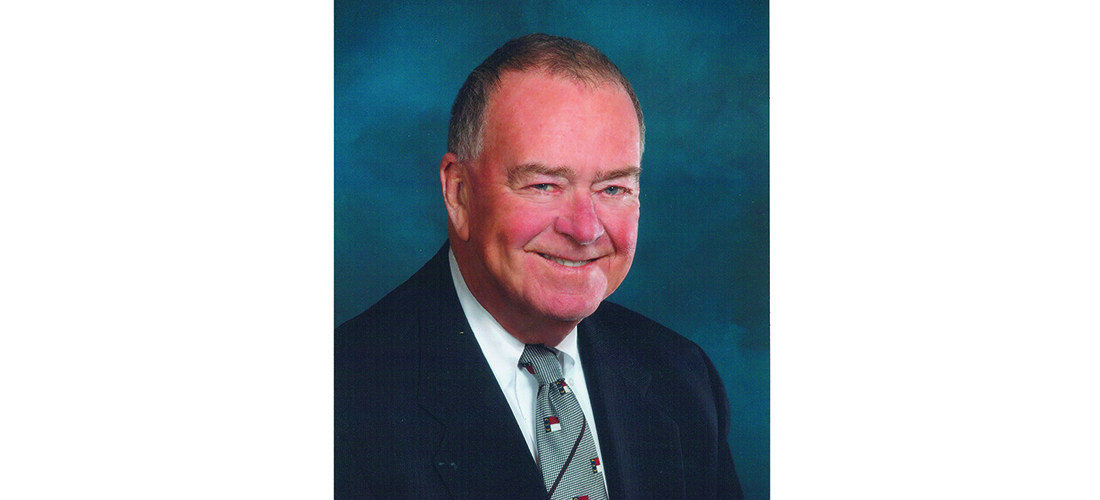

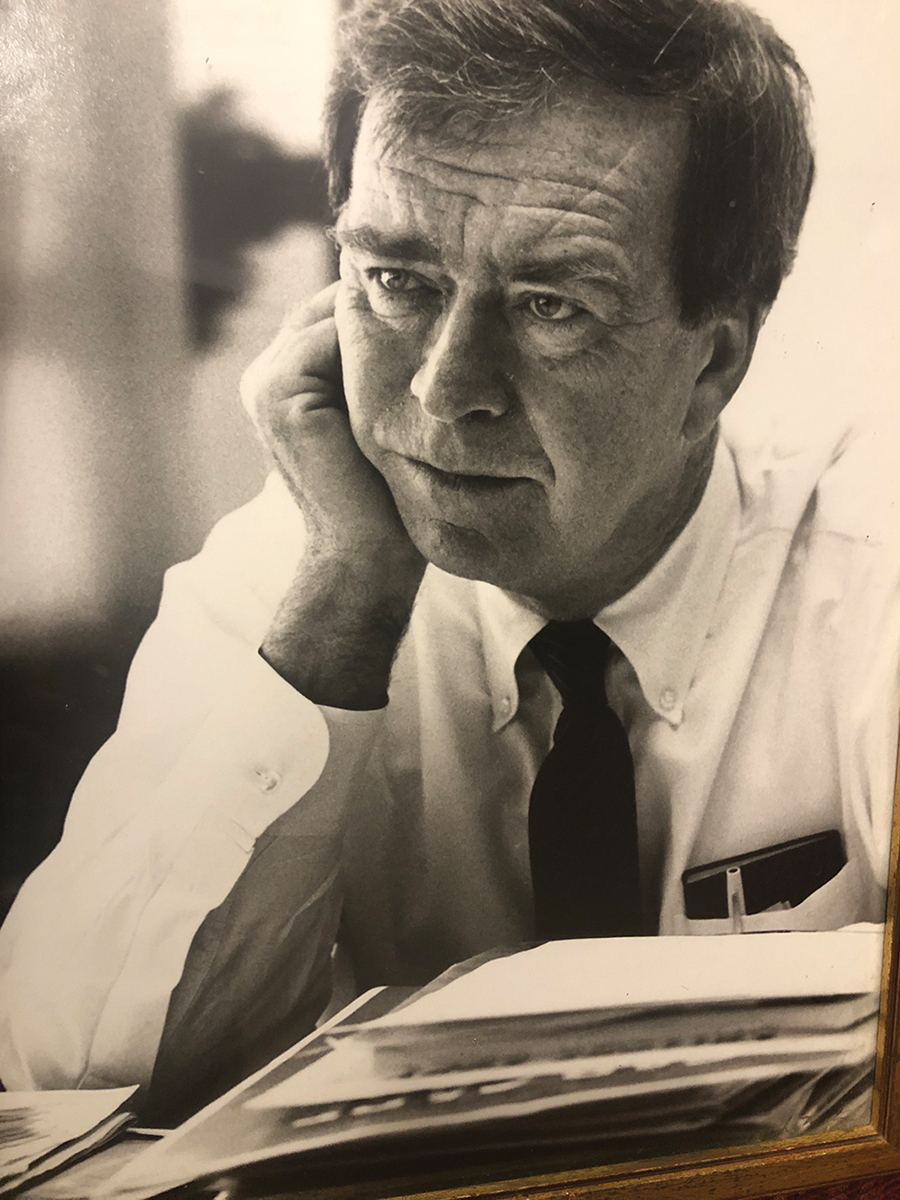

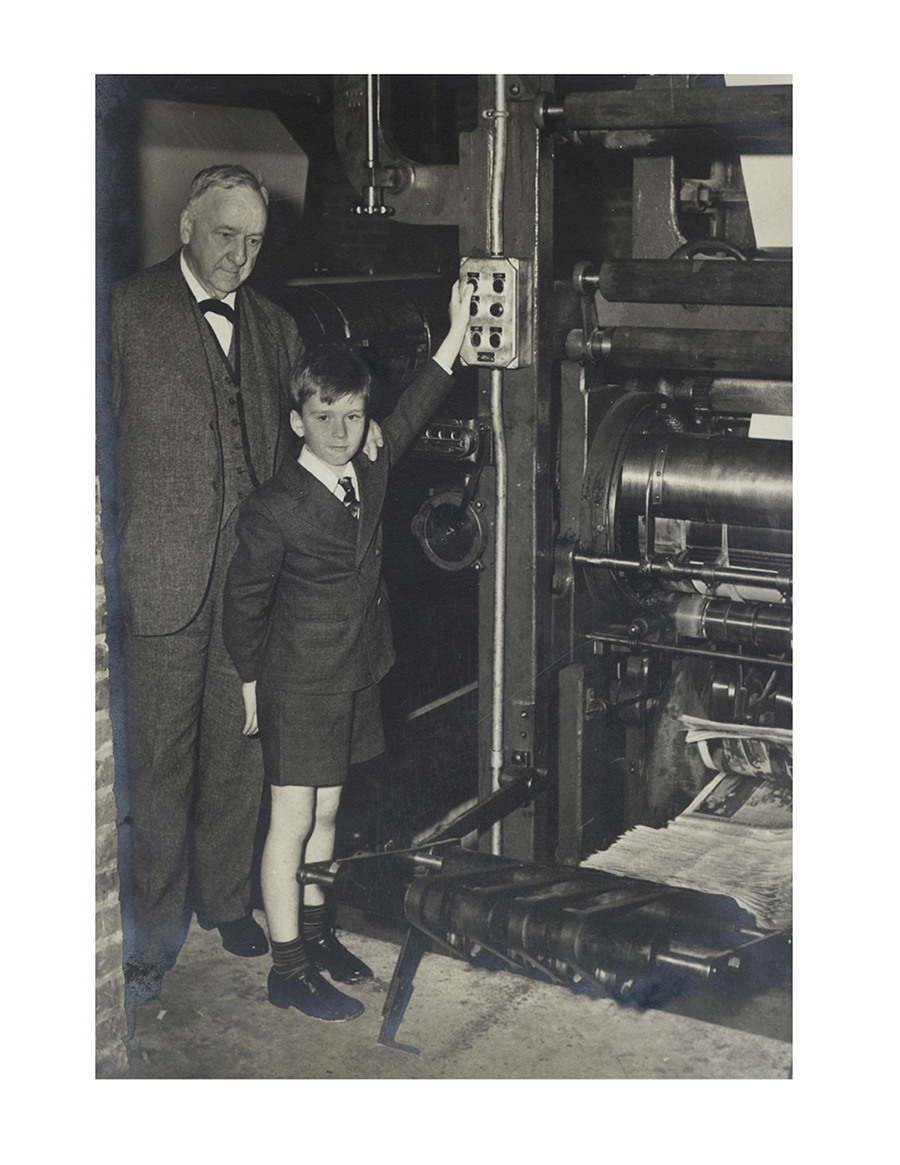

Left: Frank Daniels Jr.

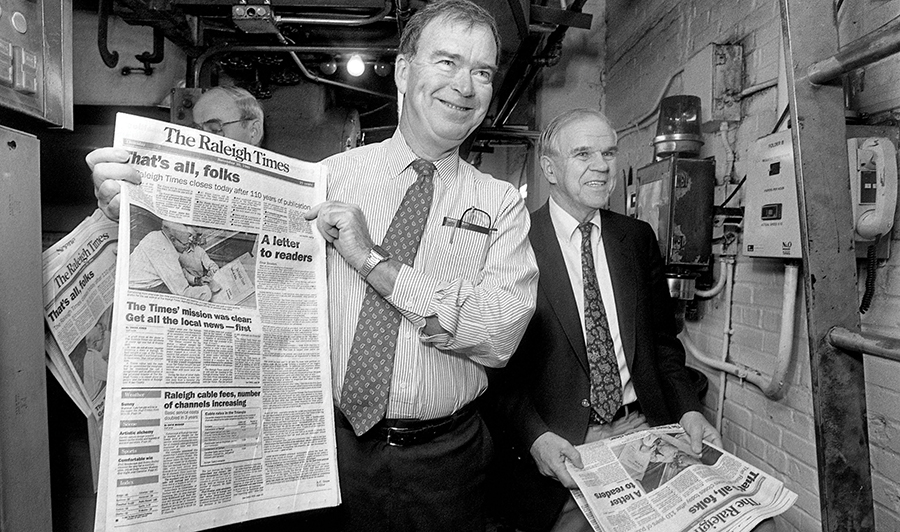

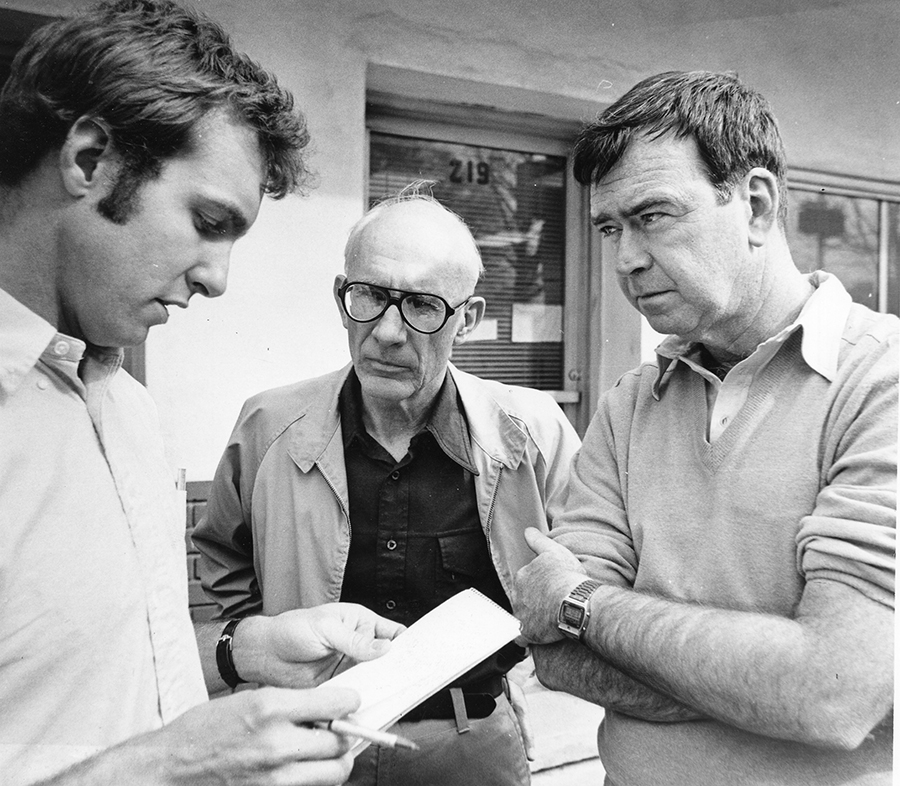

Right: Publisher Frank Daniels Jr. and Raleigh Times Editor A.C. Snow look over the final edition of the Raleigh Times.

Frank Arthur Daniels Jr. died at the age of 90 on June 30, 2022, in his hometown of Raleigh. It was the peaceful conclusion of a life full of professional accomplishment, financial success, and contributions to his community and his state. But for his multitudes of friends and family, Frank Jr. — as just about everybody called him — is remembered for his capacity to give and receive love.

Sitting in the cavernous dining area of her parents’ home on White Oak Road, Julie Daniels, Frank Jr.’s daughter, and her husband, Tom West, scan the many family portraits and mementos. There is one of her father, then 65, in front of a printing press.

“Look!” she says. “He’s got the little red book in his pocket. He always had that.”

Yes, Frank Jr. always carried a book with the names of his best friends, their phone numbers and their birthdays. When he was younger, he’d send cards; as he got older, he found it easier to call them and sing to them (and anyone who was with him would be expected to sing along).

Julie is one of two children of Frank Jr. and his wife, Julia, and her memories are exactly what her father would want them to be. “Oh, they had fun — parties all the time, events at the paper, things like that,” she says. “But they always put me and my brother first. I don’t remember that they had all kinds of money — and they didn’t think of themselves that way. But when you ask me, what was his happiest day, I’d say just about every day was his happiest.”

Frank Daniels Jr. was born at the “Old Rex Hospital,” on Sept. 7, 1931. His father, Frank Daniels Sr., was one of four brothers, three of whom were active in running The News & Observer, which was owned by Frank Jr.’s grandfather, Josephus Daniels. He attended Woodberry Forest School near Orange, Virginia, and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1953. He did two years in the U.S. Air Force in Japan and tried a year of law school but was inevitably drawn back to The N&O, which turned out to be more than his birthright — it was his destiny.

Left: Frank Jr. at press with grandfather Josephus Daniels in 1939.

Right: Publisher Frank Daniels Jr. and Raleigh Times Editor A.C. Snow look over the final edition of the Raleigh Times.

Though he and his sister, Patsy, were raised in comfort and power, Frank Jr. was a righteous man. He had a sense of right and wrong that transcended the views of the generation from which he came, and of the family from which he descended. His son Frank Daniels III recalls going to the ACC basketball tournament with his father in 1968, when he was 12. It was the first varsity year for Charles Scott, a UNC sophomore who was the first Black basketball player for the Tar Heels.

A man behind them began taunting Scott. It was something Frank’s dad tolerated until he heard the n-word. “He turned around and told the guy to shut the hell up and then said, ‘We don’t need you here.’ The guy left,” says Frank III. “That really took something.”

Frank Jr. worked various jobs in all departments at The N&O and was popular with the other workers at the paper. Sometimes he chafed a bit working for his father (who, as the publisher, ran the business operations) and his uncle Jonathan, the editor, but he stayed the course and, after working his way up, became publisher in 1971.

A big man for his time, Frank Jr. was 6 feet, 3 inches tall and burly. He had huge hands and a booming bass voice that carried through a room, though his eyes possessed a mischievous twinkle and he loved a good joke.

Gary Pearce, a longtime political strategist, remembers his boss from his own early days as an assistant city editor at The N&O in the mid-1970s. “He’d walk through the newsroom every day about 5 o’clock to go talk to Claude Sitton,” says Pearce, referring to the editor of the paper at the time. “One day, Frank’s walking through and there’s a phone ringing at an empty desk. No one’s there, so Frank — the publisher, now — puts down his briefcase, answers the phone, puts a piece of paper in the typewriter and takes down the item, a minor news brief. Then he sticks it in the basket, gathers his stuff and walks on down the hall, not saying a word to anybody. Most publishers wouldn’t have done it. That told me a lot.”

While at The N&O, Frank Jr. took some courageous stands as a fellow who owned a newspaper too liberal for many local business and community swells. He pushed for a merger of the Wake County and Raleigh schools, supporting a controversial change that led to vastly improved, integrated schools. He supported civil rights and women’s rights and didn’t balk when the newspaper started asking troubling questions about the war in Vietnam.

In addition to leading the paper, Frank Jr. rose to the top of dozens of professional associations. He was chairman of The Associated Press, and part of the leadership of nearly every civic organization in Raleigh — from United Way to school support groups to the YMCA board to chairing the boards of the North Carolina Museums of History and Natural Sciences. His board memberships and chairmanships over nine decades were too numerous to name, but his son says that his favorite post was chairman of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Board. He arranged partnerships between the Smithsonian and North Carolina’s history and science museums. They reflected his lifelong belief that everyone, at every station in life, deserved to know about art, history and science, and that the knowledge should be free.

Frank III says that his father’s seemingly natural capacity for leadership always put him in charge of whatever organization he had been asked to join. “Every group he was in, he rose to the top,” Frank III says. “I think it was his capacity for empathy. He could see what people needed, and it was important for him to help them.”

The Daniels family sold The News & Observer to the McClatchy newspaper company in California in 1995, and Frank Jr. remained as publisher until he retired in 1996.

In retirement, he became busier than ever, continuing his board memberships, staying active particularly in Democratic Party politics. Virtually every governor paid him a call. No one is sure if he ever gave a campaign contribution to a Republican. During his tenure, as with his grandfather and father, The N&O never endorsed a Republican candidate for office.

Frank Jr. bought a building on Fayetteville Street in downtown Raleigh and established an office on the sixth floor, where he entertained movers and shakers and fellow board members and politicians. Through his membership in social and golf clubs he influenced another two generations of businesspeople, candidates and entrepreneurs. Until the very last month of life, he rarely had an empty lunch date or an evening without some kind of activity.

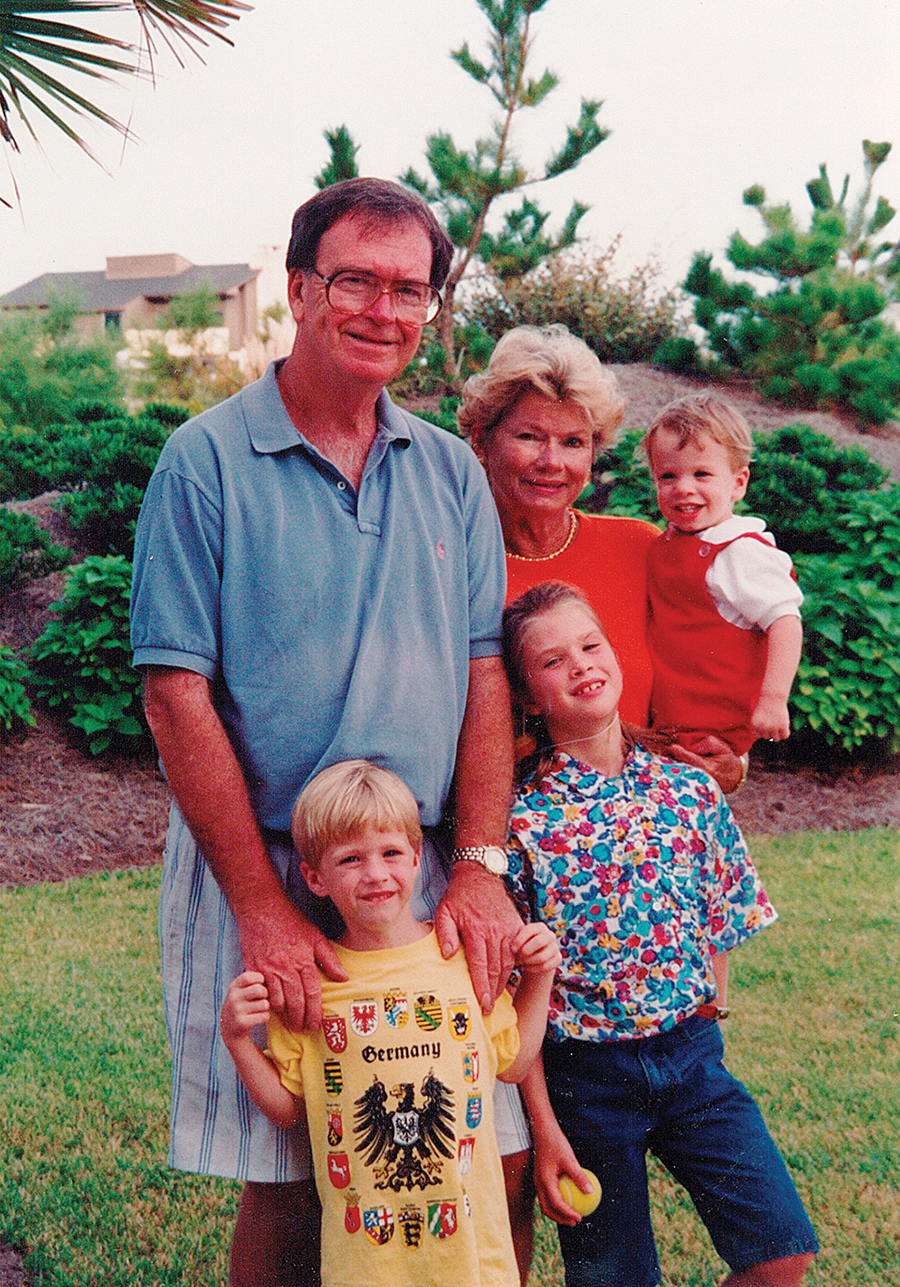

Left: Frank Jr. and David Woronoff.

Middle: Frank Jr. and Julia with Patsy Daniels-Lindley and Lucy Daniels.

Right: Frank IV, Frank Jr., Frank III.

Even after his departure from The N&O, Frank Jr. supported new ventures and publications. Shortly after his retirement, he and four others bought The Pilot in Southern Pines, then owned by Sam Ragan. Why did he do it? “It just gets in your blood,” was all he ever said.

One of the other owners is David Woronoff, Frank Jr.’s nephew. Woronoff, who runs the business for the partnership, was young at the beginning, confident but willing to ask his uncle’s advice. “He’d never let me call up and say, ‘This happened, what should I do?’” Woronoff laughs. “But he’d give advice — not that he expected you to take it.”

In one case, a prominent Pinehurst businessman called Woronoff, the publisher of The Pilot, after the newspaper was critical of a venture in which the businessman was involved. “He was screaming at me,” says Woronoff, “really rough stuff.” Woronoff called his uncle and the advice Frank Jr. gave him was unequivocal. “He said, ‘David, you never go wrong punching the biggest bully in town in the nose. What would be wrong would be if you didn’t give the person in need a hand up.’”

Frank Jr. stayed involved in the publishing group until his death, as it added The Country Bookshop, another community paper and five magazines — Business North Carolina, PineStraw, WALTER, O.Henry and SouthPark — to its stable.

Frank Jr. built friendships from childhood that lasted him a lifetime, but what he enjoyed most about all his associations was just learning. His granddaughter, Kimberly Daniels Taws, who runs The Country Bookshop, remembers visiting the beach with her grandfather when she was young. She joined him on the deck, where he was sitting next to a foot-tall stack of unusual reading material: clippings, folders, magazines, books. “I said, ‘What are you doing?’” she says. “And he said, ‘Well, I’m trying to figure out how I feel about nuclear power.’”

Many years ago, Frank Jr. hired attorney Wade Smith to help with some legal issues involving the newspaper. That led to a deep, lifelong friendship. “To me, Frank was larger than life, but Frank was real,” Smith says. “There was no putting on airs about him. He would be straight with you in all ways, and I liked that about him.”

Communications consultant Joyce Fitzpatrick met Frank Jr. when she rented space in a downtown building he owned some 20 years ago. She began regular lunches with him and Smith once or twice a month. “He was a hyper-social person,” she says. “He loved to have his lunches planned. We always typed out an agenda. It covered everything — politics, world events. People would come over to sit with us, wanting to know the latest.”

One thing he didn’t seem to have was inhibition. “Oh,” Fitzpatrick says, “we’d switch from politics to golf to what happens when we die. In the last few lunches, Wade would give comfort: We’ll see each other again.”

Perhaps, in the end, Frank Arthur Daniels Jr. is proof that a man can be great without being perfect. Frank Jr. was the first to laugh at his own flaws; he enjoyed off-color humor, indulged in profanity and played practical jokes. But if he felt he’d been too rough on someone, he’d apologize.

“From him I learned the beauty of friendship and being with other people. The importance of generosity. And that sense of humor!” says his daughter Julie. “Sometimes you don’t realize the great gifts.”

In a eulogy at his father’s funeral at White Memorial Presbyterian Church, his son, Frank III, shared a note that Frank Jr.’s longtime personal assistant, Julie Wood, found on his desk after he passed: Feed the hungry. Clothe the naked. Forgive the guilty. Welcome the stranger and the unwanted child. Care for the ill. Love your enemies.

“It’s a list of what he thought religion — and we — should teach,” says Frank III, who closed the eulogy with: “We’ll do our best.” OH

Jim Jenkins is an award-winning writer who has received North Carolina’s highest honor, the Order of the Long Leaf Pine. He retired from The News & Observer in 2018 after 31 years as an editor, columnist and chief editorial writer.

Renovation Transformation

A historic Dunleath house and the artist renovating it are forever changed

By Cynthia Adams

Photographs by Amy Freeman

When artist Susan Harrell first toured the languishing Victorian in Greensboro’s historic Dunleath, she beheld a towering, purple two-story trimmed out in cream. And that purple? “The paint was coming off in ribbons,” she says ruefully. The house soon became the artist’s agony and ecstasy.

A partial renovation had been halted before completion and it sat empty, she explains with a frown conveying the unsaid. Then in foreclosure, it was on the edge of becoming derelict. “There were squatters in the house.”

Undaunted, she jokingly dubbed it “The Purple Palace,” and made an offer.

And so began a true May/December relationship, given Harrell was only 34 at the time. The house was almost a century older than its new owner. Yet she unreservedly loved her Purple Palace.

The interior, too, was a confusion of ambitious ideas left unfinished.

By best estimates, the house is easily 122 years old, but darned if it doesn’t look great for its age today, thanks to an artist’s touch, and no small amount of dedicated labor, creative decisions and persistence.

(Pinpointing the exact age is tricky. According to the National Register nomination, the house dates to 1905. Greensboro city planner and historian Mike Cowhig, who works with the Greensboro Historical Commission, believes the property is at least five years older.)

As a full-time artist and avid DIYer who never met a power tool she didn’t like, Harrell immediately recognized the problem causing the peeling paint and knew how to solve it. The exterior had been sprayed, she says, twisting her mouth.

Bad idea.

“The siding is cedar, and you really need to brush it on.”

She painstakingly scraped the purple off, doing much of the work herself, renting a scissor lift, given the vertiginous height of the house.

“I had experience with lifts because I have done murals.” (Three of Harrell’s original murals, including a restoration, are in her hometown of Asheboro.)

And The Purple Palace would require all her gifts — both her artistic and construction abilities. And it would change her life.

Although the prior owners had made some big-ticket improvements, wiring and reworking plaster walls with sheetrock, they miscalculated costly things like a posh kitchen. Hence the foreclosure.

“They spent $900 on cabinet pulls,” Harrell explains, shaking her head. Yet there was no backsplash in the mostly-completed kitchen.

And considerable cash had been outlaid on maple flooring in the entry and main area, juxtaposed against rooms with original red oak. She throws up her hands. She stored and saved boards of the original oak for reuse or resale. After all, the upstairs renovation still awaits.

Harrell, who loves millwork and carpentry, replaced a lot of wood, including a rotting rear porch. Inside, she removed new columns that cut up the main rooms.

She changed the interior crazy quilt color scheme, calming and unifying spaces with quieter tones. After Harrell’s cosmetic touches, including a calmer color palate inside and out, the onetime home to squatters was no longer a laughing matter.

Goodbye, Purple Palace. Or “Frankenhouse,” as she started calling it.

Over the span of a century, the sizable house has led many lives, including one as a child care facility. “Maybe once a duplex, too,” Harrell guesses. “It had a parking lot in the rear.” The original staircase and entrance hall had been moved, creating an open floor plan. But an artist requires wall space for artwork.

Harrell’s plan is to eventually restore many of the original walls, truer to the house’s vintage. “There was no definition for the living room,” she laments.

Her next project? Designing a period appropriate fireplace in what is now a dining area, installing gas logs. Designed for coal, she points out, the house’s many period fireplaces were “unusually small.” On a practical level, gas logs will help with heating the 3,200 square feet of space.

Her contractor brother, “who could do things out of my realm,” is now based in Blowing Rock, managing the building of high-end homes. Having helped him on projects, she had a vision for what the restoration needed.

She has been replicating the original historic door trim, milling it herself. (It’s often impossible to find, she points out.) Harrell owns three table saws, two drill presses, planers and jigsaws, which she regularly uses.

At last, Harrell grins, she has a shop for her many tools. “I’ve done a lot of reno work. I built a loft in Asheboro.”

Is there anything she doesn’t do?

She laughs. Harrell admits she cannot make more time in a day, in order to both create artwork and do restoration work. Meantime, Harrell’s taking a break from renovation for her art’s sake.

Her greatest passion — art — is something she discovered a bit late, while in her early 20s. On her way to becoming an interior designer at Rockingham Community College, she uncovered an affinity for drawing and painting.

“I would go to a local public library and look at the art section,” Harrell explains. “I ended up in the Old Masters and decided to replicate them.” Her first effort was duplicating the legendary Mona Lisa. She discovered she had a good eye for color, and kept going.

“A hare-brained idea,” she admits modestly.

“After a few (replications), my family started noticing what I was doing. My mom has always been my biggest fan and kept encouraging me.”

All five Harrell siblings are creative. Most of them are musical.

“They all have their own weird little super power,” she says with open admiration. One brother builds high performance race car engines, netting him “multiple world records.”

Is this why she, too, is fearlessly creative? “Maybe so,” Harrell answers.

Art resonated with her more than interior design. “In the process of getting exposed to more of the arts, that’s when I started getting more interested in it,” she explains. However, she has no art school background. “I’m 100 percent self-taught.”

Harrell shows her “Musing” series, featuring miniature reflections of Old Masters within the compositions. These were key to her being discovered and admitted to art shows. “That was pretty popular. That’s how I learned how to paint.” According to one collector, she has perfected her own technique of oil painting on an aluminum panel. (Aluminum was practical — cheaper, she explains.)

She experimented with extremes in scale, from painstakingly reproducing famous paintings in miniature, paintings within paintings, to outdoor murals. Harrell was eventually commissioned to paint a mural for an Asheboro hospice, as well as aforementioned murals downtown.

While enrolled in community college, she met art teacher Melissa Walker, who introduced her to Ed Walker, her husband and the owner of Carolina Bronze Sculpture in Asheboro. For several years, Harrell fabricated bronze sculptures there, working with fiberglass, glass and clay. She even learned to weld. Fabrication was “extremely hot and heavy” — and dangerous, she concedes.

“I worked on the bronze and casing that surround the Declaration of Independence,” Harrell says proudly.

In 2001 when she was still a teenager, Harrell recalls Greensboro’s News and Record featuring her working on “February One,” James Barnhill’s iconic work, completed during 2001-2002. “I was welding together the bronze statue of the four students at A&T.”

The Greensboro Four sculpture resides on the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University campus.

By 2009, Harrell moved beyond replication of Renaissance works to her first original oils. She imparted the gripping power of the very photographs she often worked from.

Harrell explains, “I was interested in the process . . . and near photo-realism. The challenge: what it takes to make something look real. But when I got interested in art, realism wasn’t cool.”

Nonetheless, she soon found opportunity.

“When I first got into art, I got what I thought was lucky, having been invited into a group show at one of the top galleries in the country in Charleston, S.C.” She sold works as quickly as the paint dried.

For a decade, Harrell painted furiously. She looked successful.

“Everybody thought I was doing it all, right away. I was selling right away. But (some) galleries take 50 percent commissions . . . I wasn’t able to make a living.”

Harrell burned out. Flamed out, actually, and stopped exhibiting. When her contractor brother had an accident, she worked alongside him for a couple of years, learning the finer points of renovation. The physical work was satisfying.

“I need to sweat. We’re supposed to sweat.”

Harrell found renovation rewarding. And yet . . .

“I thought I’d given up on art. If you don’t have a gallery, what do you do? And most of my work was selling out of state. So, nobody in Greensboro knew I was here, and I hadn’t made those connections.”

In a strange way, the house she was busy saving saved her.

Harrell “decided to come back to art in a different way. This house was pivotal.”

She uses the word “transformation.” The transformation of the property feels like kismet, Harrell explains, walking through the gardens, a pleasing blend of stone and brickwork. Brick walkways define pathways and a sunken area features benches created from enormous river stones.

The house flows to the outside with both open and screened porches. The hardscaping was there when she acquired the property, as well as a rustic studio and abundant plantings.

There are 18 gardenias on the property. When they bloom in synchronicity with the garden’s heirloom roses, she finds bliss.

“I’ve never been into flowers . . . I’d never smelled good flowers until I moved here. And now I get it,” Harrell says. “And when they bloom, it’s like a fairy tale.”

Outdoor space, Harrell says, made the early months of COVID bearable — even enjoyable.

The former Purple Palace is quietly soothing.

Harrell’s work today includes seascapes, landscapes, still lifes and figurative paintings. She is starting a new series titled “Group Think II.”

Harrell credits recent shifts, her renewed future hopes, in part “to Nathan Wainscott.”

“She’s without question the most talented artist in the state, perhaps beyond,” opines Wainscott, a commercial artist and the owner of Inspire by Color.

He commissioned Harrell to create a painting of the Biltmore as an anniversary gift to his wife. He treasures a picture of Harrell at her easel working on the commission, saying he marvels at her work.

Wainscott calls her paintings, “stories within stories.” As a fellow artist, he finds her gifts exceptional.

Plus, he also works with both new and restoration projects, so he knows whereof he speaks. Harrell’s historic home has its own stories to tell, but he feels that she has added “the matchless talent of her artistry.”

Harrell has battled against crazy odds during the restoration, suffering brown recluse spider bites to her ankle. Given her considerable height (she is 6 feet tall) the necrotic venom “was slowed in reaching my heart and circulation.” She later fended off Lyme disease from a tick bite — all within the past six years.

Finally, it is the resurgence of her creative powers and her art that has given her a second wind.

“Something in me never wants to give up. I felt like this about the house, too.” OH

Cynthia Adams is a contributing editor of O.Henry magazine.

Life’s Funny

Stranger Things

Samaritans on the way to Summerfield

By Maria Johnson

It sounds weird to say, but I honestly don’t know how the accident happened.

I remember rolling down the Atlantic & Yadkin Greenway on my mountain bike that Friday afternoon a few months ago.

I remember coming up on the tunnel under U.S. 220, near Summerfield, and noticing that the inside walls had been painted with a bright mural. It looked like something kids had done. Was it flowers in a field?

I remember thinking it was going to be cool to pedal through the artwork and get a closer look.

But I didn’t get that far.

The next thing I knew, I was losing control of the bike and veering off the path.

Had I hit a patch of gravel where the surface changed?

Had my chain slipped?

I have no idea.

I can still feel the sickening realization that I was going down; then the shock of impact followed by a burst of pain in my shoulder; and the instant knowledge that something was broken — but not my head, thanks to my helmet.

My next memory is of three people moving toward me: a young man and woman, and, behind them, an older man with a big black-and-white dog.

The young man helped me up and allowed me to lean on him, which was a good thing because my legs were shaking. I could not have stood on my own.

He walked me over to the tunnel and suggested that I sit with my back against the wall. He asked several questions, which, even through my daze, I could tell were designed to assess my mental and physical state.

“Are you a medical person?” I asked. “Because you talk like it.”

He smiled and said no. But he’d been a lifeguard at YMCA camps and knew a lot about first aid.

The young woman pointed out the bloody scrapes on my right leg and arm.

“It’s her shoulder that I’m worried about,” he said, staring at my right collarbone.

I tried to glance down. I couldn’t see much. I didn’t really want to.

He asked if there was someone he could call.

“My husband, Jeff.”

“Do you know his number?”

“Yeah, I know his number.”

Looking back, I think it’s a small miracle that the young man — whose name I later learned was Jacob — did not call my husband and say, “Your banged-up, coherent, smart-ass wife just wrecked her bike on the greenway. Please come get her.”

Instead, Jacob told Jeff where to park and went off to meet him.

Meanwhile the young woman, Joan, and the older man, Robert — along with his dog, Pepper — stayed with me and chatted. It was amazingly amiable, considering the circumstances.

I turned to Joan: “Are you connected to the Y, too?”

No, she said. She had finished her master’s degree in counseling at UNCG and was getting ready to start a new job with a family-focused practice inside a couple of old homes on Spring Street in Greensboro.

“That’s funny,” I said, explaining that this magazine’s first office was in one of those homes.

In that moment, I could see the front room where our young editor hung her dream catcher, the wonky, windowless room that connected the front room to the kitchen. I could see the staircase, the landing, the upstairs room where our crew draped ourselves over armchairs and a futon to laugh and curse and argue and conjure a never-ending stream of story ideas.

Soon, Joan would come to know the same spaces through her work with young children.

A feeling hit me. It was more woo-woo than woozy.

I turned to Robert.

“What about you? Are you retired — to be walking your dog in the middle of the day?” I asked him.

Yes, he said, from the old post office on Banking Street.

Again, the small-world feeling washed over me.

I told him that O.Henry’s second office was in the Dutch-barn-shaped building next door. I used to mention the old post office as a landmark when giving people directions because everyone seemed to know where it was.

“That was a great post office,” I said sincerely.

Robert nodded.

It occurred to me that there must have been times when we were working within Bluetooth range of each other.

So far, only a few yards and years had separated me, Robert and Joan. And now, here we were, the three of us, hanging out under a highway on a Friday afternoon.

It was as if time and space had folded so that we finally met face-to-face just when I needed them most.

“Well,” I said to my tunnel peeps, “I hope no one else shows up because I’m running out of former workplaces to have in common.”

They stayed with me until Jacob returned with Jeff, who whisked me to an emergency room.

Joan and Jacob took my bike — they had a rack on their car — and dropped it off at our house.

Five hours later, an emergency room doctor confirmed that my collarbone was broken in a couple of places

A few days after that, an orthopedist assured me the bones would knit without surgery if I kept my right side quiet for eight weeks.

That was 12 weeks ago.

The road rash scabs have been replaced by shiny, pink skin.

My sling is folded up in a closet.

I’m doing physical therapy to regain strength.

The bone-deep ache is fading.

What persists, though, is the memory of three strangers who ran to my aid. They knew nothing about me — where I lived, how I voted, what I believed, whom I loved.

None of that mattered. They saw I was hurting and — maybe because my need was so obvious — they responded with care.

Once they came closer, we found we had things in common.

It sounds weird to say, but that gave me hope — in the midst of pain.

And for that, I am thankful. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. Contact her at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

The Creators of N.C.

Renaissance Bartender

Joel Finsel mixes books and bourbon

By Wiley Cash

Photographs By Mallory Cash

When you sidle up to the bar before ordering a beer or cocktail, you probably don’t expect your bartender to have authored two books and numerous articles, have a graduate degree in liberal studies, or to be a leading advocate in the movement for historical justice. But if you know Joel Finsel and he is the one behind the bar, then that’s exactly what you would expect. You would also expect a very, very good drink.

One crisp day in early fall I spent an hour or so with Joel in downtown Wilmington at the Brooklyn Arts Center, a gorgeous, deconsecrated church that was built in 1888 and passed through the hands of numerous congregations before falling into disrepair and being saved by a public and private partnership in the late 1990s. Over the past decade, the Brooklyn Arts Center has hosted countless weddings, community events and concerts by musicians like Art Garfunkel, Brandi Carlile and Old Crow Medicine Show. The sprawling complex, which features the event space, a bridal suite, an annex that once served as an old schoolhouse, a courtyard and the Bell Tower Tasting Room, is now a busy hub of art, culture and celebration. It was in the Bell Tower Tasting Room where I found Joel, ready and waiting to mix up a few cocktails that are perfect for the upcoming holiday season.

As Joel mixes our first cocktail — a mulled apple cider — I ask him how he’s been able to build a career as a bartender with one foot in the literary world, another in modern art and another (apparently Joel has three feet) in bartending. He smiles. “I think I’ve always been attracted to chaos,” he says, which surprises me. Joel is one of the most measured people I’ve ever met, and to watch him work behind the bar is to witness a seemingly effortless precision.

The steaming hot apple cider is poured with bourbon and garnished with star anise, lemon and a cinnamon stick stirrer. It tastes like a winter evening, presents wrapped under the tree and the kids blessedly asleep before the chaos of Christmas morning.

I ask Joel about his childhood growing up in Lehighton, Pennsylvania, a small blue collar town on the banks of the Lehigh River about an hour and a half northwest of Philadelphia.

“Until I was 5, my family lived in a trailer on a dirt road, 2 miles up along the side of a mountain. It was awesome because there were bears and deer, and you could just pick up rocks and there were orange salamanders everywhere,” he says. “And then my great-grandmother passed away and we moved into her house in town, which changed everything for me. I was suddenly in the middle of a small town and I could walk to high school and there were girls there. And there was a basketball court nearby, which I pretty much lived at.”

The abstract expressionist painter Franz Kline also moved to Lehighton in his youth in the second decade of the 20th century. Joel’s mother had grown up in the area hearing stories about Kline and his work, and her interest led her to become one of the country’s pre-eminent specialists on everything from Kline’s paintings to his career and biography. When Joel was young, his mother began working on a biography of Kline, but it wasn’t until Joel graduated from college and was teaching school in Philadelphia that he asked for a look at the manuscript.

“I was home for Christmas, and I said, ‘Mom, what’s up with that book?’ I asked her if I could take a look at it. And then I realized what she had was a huge document of notes, but no structure.” Mother and son began working on the project together, and they would do so for over 20 years before Franz Kline in Coal Country was published in 2019, the first biography to examine this major American artist’s formative years in Pennsylvania, Boston and London before he became one of the founding members of the New York School.

The next cocktail Joel prepares is called the Cat’s Whiskers, a tipple of rye whiskey, honey syrup, fresh lemon juice and Angostura bitters that tastes like a party thrown by Jay Gatsby. If I were to turn and look over the balcony here at the Brooklyn Arts Center, I would almost expect to see a jazz band taking the stage, the audience filled with men in smart suits and women in flapper dresses, snow pounding against the stained glass windows as the hour tips past midnight.

The book on Kline was not the first Joel had published. During a long career as a bartender — one that began in college and would lead to reviews and spots in publications like Bartender Magazine, Cosmopolitan and a profile in Playboy as one of the country’s Top 10 Mixologists — Joel had accumulated countless stories from co-workers and patrons, many of which he recounted in his 2009 book Cocktails & Conversations, which expertly mixes barroom lore with the histories of mixology and cocktail recipes.

One bar customer who had an enormous influence on Joel’s life was the abstract expressionist Edward Meneeley, a contemporary and friend of artists like Willem de Kooning and Andy Warhol. Joel and Meneeley met while Joel was in college at Kutztown University and working at a bar across the street from Meneeley’s art studio.

“Ed introduced me to mixing things like Campari and soda back in the day when everyone drank Captain and Coke, circa 1998,” Joel says. “Ed would come into the bar and throw his old copies of The New Yorker at me and tell me I needed to educate myself out of this town, so I got to know the work of the magazine’s art critic Peter Schjeldahl pretty well. I wasn’t even 21 yet. I started tending bar at 18, which was legal.”

The next cocktail Joel makes is called Lavender 75, and while it doesn’t include Campari, the West Indian orange bitters combine with gin, fresh lemon, lavender syrup and a splash of dry Champagne to give the drink an incredibly complex and layered taste, both dry and deeply flavorful.

When Joel and his wife, Jess James (who owns a vintage clothing boutique in Wilmington that is a habitual stop for Hollywood actors when they’re in town filming movies), moved to town in 2005, Joel brought his two main interests south with him: mixology and contemporary art. He took a job as the bartender of Café Phoenix in downtown Wilmington and designed one of the first craft cocktail menus in the city. He also curated the art on the restaurant’s walls, hosting artists like his friend Meneeley and Leon Schenker. Suddenly work by internationally known artists valued at tens of thousands of dollars was hanging where local art had once dominated the walls.

It was after a few years in Wilmington, where he eventually earned an MA in liberal studies from UNC Wilmington, that Joel first learned about the 1898 race massacre, the only successful coup in American history that saw white supremacists murder untold numbers of Black citizens while overthrowing the duly elected local government. He was shocked to learn that something so horrible had happened in a city he had quickly grown to love.

After researching the events surrounding 1898, Joel co-founded the nonprofit Third Person Project, which is dedicated to uncovering and preserving history. One of the group’s first projects was gathering and digitizing copies of The Daily Record, which was the only daily Black newspaper in North Carolina before it was destroyed by a mob during the events of 1898. Since then, the organization has gone on to host musicians like Rhiannon Giddens, who came to Wilmington to perform the “Songs of 1898” at a 2018 event with Joel’s Third Person co-founder, writer John Jeremiah Sullivan. Third Person has gone on to lead Wilmington in efforts to save historic buildings, mark burial places, and uncover lost histories, often by partnering with local institutions like UNC Wilmington’s Equity Institute.

On a smaller scale, Joel is also contributing to local history with the impact he’s had on its cocktail scene. The final drink he mixes — the True Blue — is a good example. He created it years ago when he designed the cocktail menu for the Wilmington restaurant True Blue Butcher and Table. The cocktail remains a fixture and, with its mix of pear-infused vodka, elderflower liqueur, lemon and a splash of dry Champagne, I understand why.

Our interview is over and, as Joel cleans up behind the bar, he tells me he plans to spend the rest of the afternoon working on an essay about 1898. Cocktails, conversation, curating art, correcting history. It’s all in a day’s work.

True Blue

Fresh, clean, bright. Designed after research into ancient Greek formulas for the “nectar of the gods.”

1 ounce Grey Goose La Poire vodka

1 ounce St. Elder elderflower liqueur

1/2 ounce fresh lemon (or about half

a lemon)

Splash dry Champagne

Splash sparkling mineral water

Pre-chill cocktail coupe and set aside. Mix vodka, elderflower liqueur and fresh lemon over ice in a mixing glass. Shake hard for at least 12 seconds. Discard ice from pre-chilled coupe back into ice bin. Strain mixture into coupe. Float Champagne and soda. Garnish by dropping in 3 blueberries or thin slice of pear.

The Cat’s Whiskers

Substitute gin and it becomes The Bees Knees. Both are Roaring ’20s slang for the height of excellence.

1 3/4 ounces favorite bourbon or rye whisky

1 ounce honey syrup (1:1 ratio of hot water to honey)

3-4 fresh mint leaves

1/2 ounce fresh lemon

2 dashes Angostura bitters (optional)

Splash sparkling water

Pre-chill cocktail coupe and set aside. Combine all of the ingredients over ice and shake for 12 seconds. Discard ice from pre-chilled coupe back into ice bin. Double strain into coupe (make sure no green flecks of mint end up in anyone’s teeth). Garnish with fresh mint top.

Lavender 75

The classic French 75 cocktail was named after a cannon. This places a flower in the barrel.

1 1/2 ounces Botany Gin

1/2 ounce fresh lemon

1 ounce lavender syrup (steep dried lavender flowers like a tea in hot water, then add sugar, 1:1 ratio)

3 dashes West Indies Orange Bitters

Splash dry Champagne

Splash sparkling mineral water

Pre-chill a cocktail coupe and set aside. Combine all of the ingredients over ice and shake for at least 12 seconds. Discard ice from pre-chilled coupe back into ice bin. Strain the chilled mixture into the coupe. Garnish with 3-4 dried lavender buds. OH

Wiley Cash is the Alumni Author-in-Residence at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. His new novel, When Ghosts Come Home, is available wherever books are sold.

Tea Leaf Astrologer

Scorpio

(October 23 – November 21)

They say one rotten apple spoils the barrel. Let’s put it this way: Your thoughts are the apples. While you aren’t prone to having more wormy ones, per se, you’re certainly more inclined to hold onto them. Grudges, in particular. Those closest to you can sense when you’re stewing, but no one knows how dismal it can feel to be dancing to the same noxious tune ad nauseum. Remember that you’re the DJ. Forgiveness is a gift to yourself.

Tea leaf “fortunes” for the rest of you:

Sagittarius (November 22 – December 21)

Best not to think twice.

Capricorn (December 22 – January 19)

Let them talk. You know the truth.

Aquarius (January 20 – February 18)

Set an extra plate at the table.

Pisces (February 19 – March 20)

Chew before you swallow.

Aries (March 21 – April 19)

Bring a poncho.

Taurus (April 20 – May 20)

This might sting: There’s nothing between the lines.

Gemini (May 21 – June 20)

Try rotating your mattress.

Cancer (June 21 – July 22)

Wear the dang sweater.

Leo (July 23 – August 22)

You’re asking the wrong question.

Virgo (August 23 – September 22)

Go for the store-bought.

Libra (September 23 – October 22)

Something’s overheating. (Hint: It’s not dinner.) OH

Zora Stellanova has been divining with tea leaves since Game of Thrones’ Starbucks cup mishap of 2019. While she’s not exactly a medium, she’s far from average. She lives in the N.C. foothills with her Sphynx cat, Lyla.