Fashion-ating Rhythm

When it comes to Greensboro’s sense of style, past is prologue

By Billy Ingram

Photograph © Carol W. Martin/Greensboro History Museum Collection

In 2009, I opened the newspaper to see an enormous color photo taken on State Street of my mother, Frances Ingram, doing what she loved most: shopping. How apropos, I thought. Mom made the rounds to her favorite shops, an ever dwindling number as she grew older, every single day.

As a youngster in the early-1960s, one of my earliest memories was Mother getting all dolled up to cruise the downtown department stores for clothes to wear the next time she went out shopping. A holiday highlight was a trip to Ellis Stone to meet Santa, who handed out wrapped gifts from under a fireplace made from shoeboxes and wrapping paper. Department store windows at Belk, Meyer’s, Montaldo’s and Ellis Stone were glittering, snowy greeting cards come to life.

Julian Wright, one of the brave souls who stormed the beaches of Normandy, found his post-war calling staging those lavish, dioramic window displays for Ellis Stone in the 1950s throughout the ’60s and, then, after the store was rebranded as Thalhimers. Wright’s idealized snapshots of American life, defined and enhanced by the products being peddled, became genuine tourist attractions with adults and children alike nose-to-glass, eyes awash in every vivid detail.

Little did little-me know I was witnessing the beginning of the end of shopping as a spectator sport.

By the early 1900s, men could buy off the rack, but there was no such thing as ready-to-wear women’s clothing when Vanstory and Belk opened their small, downtown Greensboro dry goods stores alongside a newly brick-and-block paved street called Elm. Both carried everything a woman required — silk, cotton, wool, buttons, laces and lacings — to construct her own frocks and even undergarments.

For society doyennes, the fashion of the day was pleated, flared skirts down to the floor with tight-waisted bodices and Leg o’mutton sleeves. That level of intricacy required the services of Mrs. T. W. Hancock, a renowned dressmaker on West Fourth Street in Winston-Salem. “Miss Molly” purchased fabrics and finery on her frequent forays into New York City, paying a handsome price for the latest Parisian haute couture patterns. She employed a retinue of seamstresses and cutters to fabricate exquisite wardrobe pieces for everyone who was anyone in the region.

Ellis Stone was well-established in Durham before launching a Greensboro location in 1902. Today the name is enshrined above the entrance at 226 South Elm. Foreshadowing the dawn of the full-service department store, Ellis Stone began taking ladies’ measurements, then dispatching them to New York for tailor-made suits and dresses. As it gained a reputation for being the epitome of taste and style, Ellis Stone made its home across the street (most recently Elm Street Center) in a $1.5 million, starkly modern 78,000-square-foot shopping mecca with a spectacular winding marble staircase, 20-foot tall mirrors and richly appointed sales floors.

Just down the street, in 1924, the city’s first enclosed shopping mall opened on the ground floor of the Jefferson Standard Building in 1924 with a barber, dentist and clothiers including Vanstory Clothing Co., founded across the street around the turn of the century. Vanstory catered to the city’s elite, offering Botany 500 suits and Don Roper ties. Flanking Vanstory’s entrance were some positively surrealist window displays, overly-starched shirt sleeves folded meticulously into tightly wrapped geometric puzzles, everything in frame cocooned in a warmly lit, thickly lacquered wooden cavern. Very European.

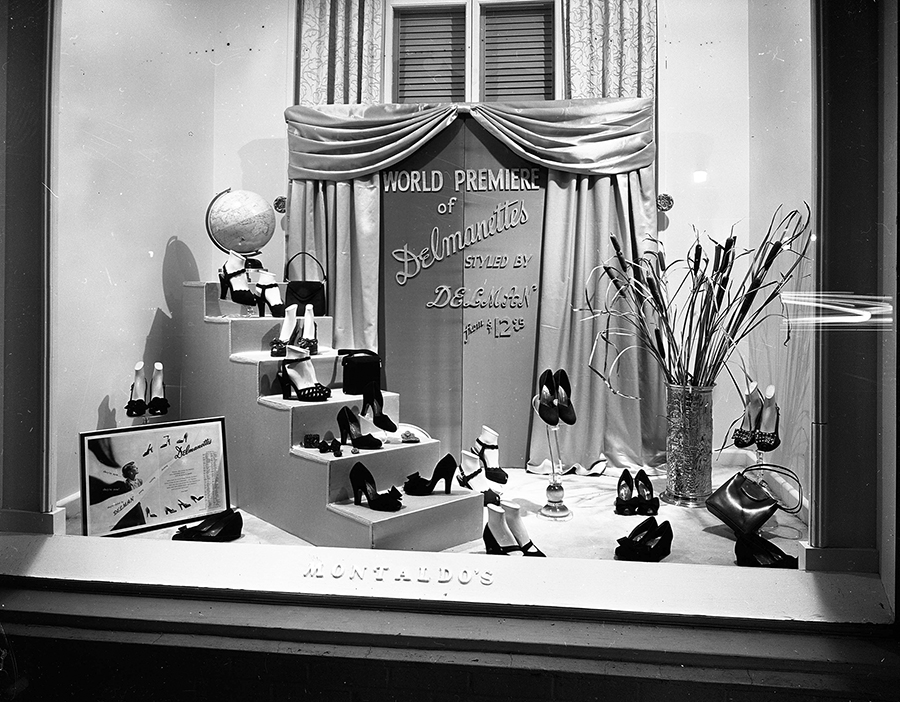

Vanstory rented out a portion of its storefront in 1933 to Montaldo’s, a small chain specializing in high end, ready-to-wear dresses run by two sisters out of Kansas. “When Montaldo’s came to Greensboro, that kind of upped the game,” fashion maven and owner of Design Archives Kit Rodenbough says. “Before that everybody had custom dress makers. Montaldo’s would have an outfit from a designer modeled in the store and women would order it in a custom fit.” Montaldo’s became a beacon of elegance on the corner of Elm and Friendly in 1942 when it moved into its curvaceous, two-story white-brick building. The front door looked more like a modern home than a commercial enterprise. And its wide windows displayed a dazzling array of wedding gowns, lingerie, millinery and cosmetics.

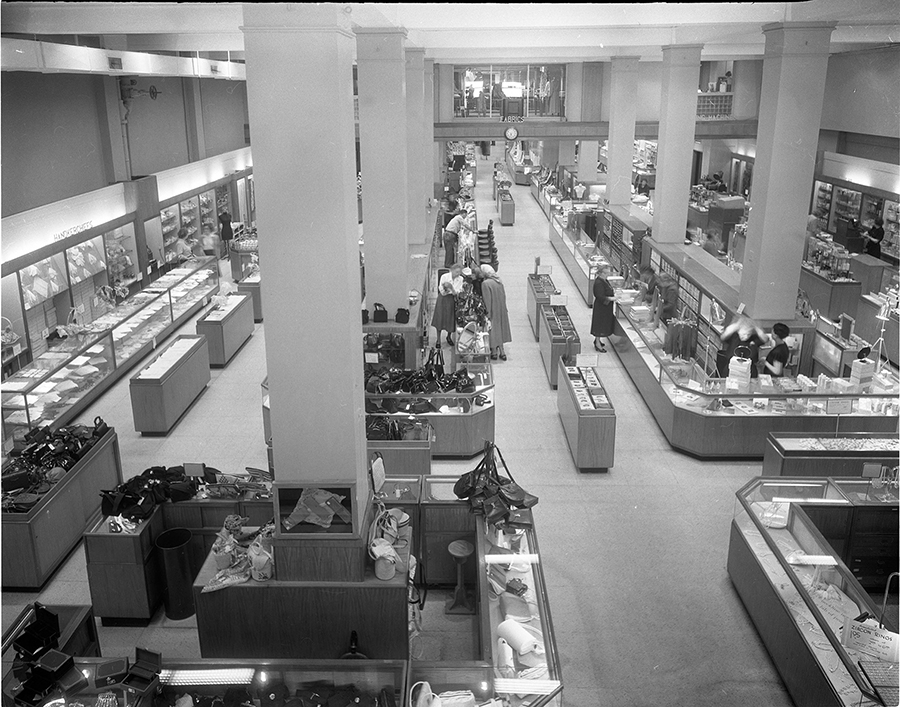

Meyer’s Department Store got underway around 1910, but it wasn’t until 1924 that it welcomed customers for the first time into a magnificent five-story showplace on the corner of Elm and Sycamore (now February One Place). Most striking to modern eyes would be the spacious aisles, neat glass and wooden cases, and finely dressed men and women standing at the ready to offer assistance. Sweaters and slacks in various colors and sizes lay neatly on tabletops with wardrobe essentials like dress shirts, gloves and undergarments displayed inside transparent enclosures. There was very little you couldn’t find at Meyer’s with its story after story sales floors staffed by over 500 employees. The operation eventually took up an entire city block, comprising a veritable shopping mall before such a thing existed, with 700 brand names under one roof, everything from “bobby pins to refrigerators.”

Left & Middle: Meyer’s

Right: Brownhill

Best of all, department stores had their own credit system. Customers need only scribble their names on the bill of sale and be on their way, merchandise in hand. Itemized bills arrived in the mail at the end of each month and were generally paid by mail.

In 1925, decorated in canary-colored walls and upholstery, primary-colored plaid curtains adorning floor-to-ceiling windows lining the Sycamore Street side, Meyer’s Tea Room opened on the second floor for afternoon light lunch. For the 53 years of its existence, the decor changed, but the menu not so much — everything prepared fresh, never canned. “My mother was a hairdresser so she always had Mondays off,” Charlie Hensley recalls of his childhood, circa 1960. “Often we would have lunch with my grandmother at Meyer’s Tea Room. The shopping experience was a lot more civilized back then, especially with the Tea Room, like an immersive experience. My mother was still wearing hat and gloves to go shopping then.”

The Belk brothers of Charlotte christened their first store in Monroe in 1888. A decade later, they opened a Greensboro branch. In 1939, they cut the ribbon on a Charles C. Hartmann-designed palace at Elm and Market. An exterior of glass and stone on the street level, glass brick detailing on the second and third floors, it took three boxcars worth of walnut to construct the hundreds of display cases, accented with birds-eye maple and primavera. Besides clothing, Belk offered a full-service beauty salon, candy counter, and cosmetics department.

Hensley’s first job as a teenager was as a sales associate at Belk downtown in the late-1960s. “It was the first time that I realized if you worked retail that you got a discount,” he told me. “The guy who ran the store was Mr. D.O. Tice, who looked a little like J. Edgar Hoover. I always thought he was a bit of a bulldog. When he would come through, the crowd would part. I don’t remember him being unpleasant ever, just formidable.” Hensley’s clients were very well-dressed matrons. “Part of what they expected from me as a 14- or 15-year-old was to be the expert advising them about what their husbands would like or what their sons might want.”

Two clothiers, Sam Prago and Adolph Guyes, joined forces in 1940 to create what would become an empire with four Greensboro locations and multiple stores scattered across the state by the 1970s. Down the block from Belk at the Dixie Building, across from Woolworth’s, Prago-Guyes’ lit-from-behind, emblematic logo glowed atop an entranceway bathed in color and light. Surrounding customers as they arrived were wraparound windows adorned with the latest ensembles. Another glass casement stood in the center of this impressive frontage. Their vast shoe department tickled the air with the scent of leather and vinyl. If you wanted to be hip to the latest gear, Prago-Guyes bragged, “We’re In Touch.”

Laurie’s Sportswear, popular with the Jet Set since opening on Elm in 1951, became the first major downtown retailer to close up shop and head for the suburbs when Laurie Queen and her three brothers signed on as an original tenant of Friendly Shopping Center in 1957. “I just thought it was beautiful,” Carolyn Andrews-Allred says of the spacious showroom, since repurposed for Harper’s restaurant. “I started working for Laurie’s my last year at Grimsley in the spring of 1972. It was the only place I wanted to work.” Harland Pell was its window designer, “I learned how to ‘fly the merchandise.’ That’s what they call it, to make garments hang in the air kind of magically with fishing wire.” Managers and brothers Edward and Marshall Simon had taken over operations by then. “Very strict business people,” Andrews-Allred says. “If somebody came in two minutes late, they were fired immediately.”

Salespersons were instructed in an almost mathematical method for moving merchandise. “We used it to sell not just one item, not just a dress or a blouse,” Andrews-Allred notes, “but you could figure out how to sell an entire set of clothing.” Very effective, at least in one sense. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, these people are buying so much — this is great,’” only to discover customers returning a large percentage of their purchases. “That’s just the way the fashion business was. You bought a lot and returned a lot.”

Left & Right: Montaldo’s

After leaving Laurie’s, Andrews-Allred took a sales position at Brownhill’s downtown in the mid-1970s. “It was much tinier, very much upscale,” she recalls. “Much more formal, like Montaldo’s.” Brownhill’s was established in 1927 when Elmer Brownhill arrived from England to open “a shop for stylish gentlewomen.” Before long the image of the “Brownhill’s lady” became iconic. Lewis and Adele Rosenberg bought the store in 1945, instituting Breakfast at Brownhill’s, a catered Saturday affair with models in the latest outfits strolling the aisles. Longtime employee Jack McGinn took ownership in 1963, his refined taste further cementing Brownhill’s impeccable reputation. Plushly carpeted throughout, there was a posh mezzanine level shoe emporium that the well-heeled accessed via a curved stairway.

While Brownhill’s added a charming storefront at Friendly, they remained downtown until 1987, long after every other upper-cruster had fled the scene. Over the years it gained the reputation as the primary go-to spots for prom dresses and debutante gowns. “They made sure if they did sell a gown to somebody that they weren’t attending the same gala as someone else who bought the same dress,” Andrews-Allred says.

For decades, consistency and uncompromising quality were the hallmarks of Younts-DeBoe located across from the Jefferson building since 1929. As a pre-teen, I can recall tagging along with dear old Dad once a year to be fitted for a new spring sport coat. With ladies’ tailored clothing at ground level and men’s and boys’ on the second floor, what is most memorable to me was the elevator operated by a gentleman who greeted us with a wide grin, “Good morning Mr. Ingram, watch your step.” An anachronism by 1970, long after others automated their lifts, Younts-DeBoe steadfastly refused to break with tradition.

Left & Right: Meyer’s

Younts-DeBoe was home of the Greensboro Nettleton, a prestigious soft leather loafer that will set you back about $600 today. “The shoe originated out of New York,” says long-time fashion consultant Dan Dellinger, who bought his first pair as an eighth grader at Kiser Junior High in the ’60s. “At that time they were $27.95. It’s not the same shoe. Today it’s fully leather-lined and has a thicker sole than the original, which had a canvas lining with partial leather, a much lighter weight.” Still, adjusted for inflation, a pair of Nettleton loafter purchased in 1965 for $27.95 would cost the equivalent of $258 today.

Younts-DeBoe was acquired by Henderson Belk in 1980 with the stated intention of leaving this downtown mainstay open. Regardless, just a year later, it fell upon previous owner Hank Millican, who had been with the store from the very beginning, to oversee the dismantling of the solid oak showcases built in 1929 for a short-lived relocation to Four Seasons Mall, about which the less said the better. You can still see Younts-DeBoe’s logo inlaid in the marble flooring in the lobby and embossed into the sandstone exterior at 106 North Elm.

In-store fashion shows were heavily attended events in the 1940s and ’50s. By the late-1960s, Greensboro’s Fashion Week came in October with a runway show held in the main room of the Coliseum. “It was a huge thing for a few years,” Charlie Hensley told me about his brief fling as a model. “Sandy Forman used to direct this thing and it was very posh, high production values, very well mapped out.” Staging was constructed for the event and a live band accompanied the show. “Backstage they gave you boxes of clothes. Everything was racked according to the model.” A representative from every store was standing in the wings to review everyone’s look before they strutted forward. “I modeled for Joel Fleishman who had a store at Friendly. My God,” Hensley gasps, “those were beautiful clothes.”

Right: Belk’s Department Store, 1951

Left: Montaldo’s, 1953

In the ’70s, the program migrated over to the Carolina Theatre where 15-year-old John Shepherd walked the runway wearing clothing from his parents’ store, Bernard Shepherd, “which I hated but I got roped into it.” Shepherd says, “Mom would come up to all the male models and slap a Kotex mini pad under our armpits so we wouldn’t perspire on the shirts because they were going back into stock.”

My family frequented Bernard Shepherd at Friendly ever since the grand opening in 1967. It’s where the menfolk bought all of our suits while my mother was often outfitted from the ladies’ section up front. John Shepherd began working for his parents, Bernard and Eleanor, in 1987 at 19 years old. Primarily a men’s outfitter, Bernard Shepherd carried high-end traditional menswear lines with the option of being measured for a custom fitted suit. “We had a box full of swatches you could go through to pick your fabric, lining, your buttons, everything,” Shepherd says. Clothing manufacturing reps with their goods hanging on racks rolled into the office at the rear of the store, “Or they showed up in big motor homes parked behind the store. They had all of their latest styles displayed inside.”

The malling of America had a chilling effect on traditional mom-and-pop retailers. To combat this phenomenon in 1976, Starmount, Friendly Center’s owner, introduced Forum VI nearby with a promise of being Greensboro’s climate controlled, bougie apparel and dining destination. Anchored by Montaldo’s after they finally closed what had become their downtown tomb on Elm and Friendly, the city’s fashion shows were now held at the Forum.

Shopping malls were fully open on the sabbath, which is why, beginning in 1990, Starmount required all tenants at Friendly Center to conduct business seven days a week. The Shepherds were against doing so on religious grounds. They sued and won what was a pyrrhic victory. “Starmount threatened to padlock the store,” John Shepherd tells me, which they apparently had a right to do. An agreement was forged in 1990. The store could stay closed on Sundays, Shepherd recalls, “but Starmount would pay to outfit a new store and build it out at Forum VI.”

Right: Belk’s Department Store, 1951

Left: Meyer’s Department Store

That same year and for the same reason, Brownhill’s was redirected into Forum VI. Both stores experienced a steep decline in sales. For a multitude of reasons, Forum VI never really caught on. Montaldo’s liquidated all of its stores in 1995, and Bernard Shepherd was shuttered a few months later. After almost 70 years in Greensboro, Brownhill’s sold everything, down to the fixtures, in 1996.

In terms of fashion locally, it became a race to the bottom when Cone Mills instituted dress down Fridays in the 1990s. Around that same period, VF downtown went every-day-casual, with others quickly following. “As it progressed,” Dan Dellinger points out, “some people looked like they were mowing yards when they came in to buy clothes.” Employee standards dropped so low at VF, it had to initiate a dress code. “Casual Fridays at the office, that was the beginning of the end,” Kit Rodenbough says with a sigh. “Once the men didn’t have to wear neckties and suits every day, the women were like, you know, [forget] this!”

Downtown, Meyer’s intricately detailed, monolithic 1924 castle is intact, serving a useful purpose as headquarters for the Chamber of Commerce and others, but Belk and Montaldo’s former residences long ago succumbed to the wrecking ball. Ellis Stone/Elm Street Center has a date with one, having already been stripped clean of every sumptuous design element.

Laurie’s at Friendly Shopping Center, 1970s-1980s

Seeking continuity? At 530 South Elm, Laurie’s original 1951 location, you can pursue your passion for fashion at Vintage to Vogue. Plaza Shopping Center and the cluster of 1950s era bungalows behind it on Pembroke remains a fashion-forward location for women and children just as it was in the 1960s and ’70s when Prago-Guyes had a storefront there and Lollipop Shop was a long-time tenant. On Pembroke behind Plaza in the ’50s, my grandmother enjoyed the ambiance at Helen Mulvey’s Handicraft House, which sold Yankee Peddler cotton dresses and country shirts.

Locally sourced panache still bubbles over in boutiques at Plaza Shopping Center: The Feathered Nest for ladies and Polliwogs for the kiddos. Steps away, next door to the former Handicraft House, is my late mother’s favorite place in town, Carolyn Todd’s. “They have the correct cheese straws,” she would remind us every holiday season. Her last Christmas, I accompanied Mother to Carolyn Todd’s, where she procured a major portion of her presents that morning. As we were checking out I watched bemused as — this was just a few years ago — she signed for her purchases and we were on our way. OH

Billy Ingram’s fave article of clothing is a 1960s Sy Devore short-sleeved, striped knit shirt once worn by Frank Sinatra.

World War II brought shortages of everything from denim to nylon, essential goods diverted to shore up our troops. At war’s end, when word got around that the first shipment of nylon stockings in four years would be available at Meyer’s on a morning in 1946, a line of nattily attired ladies began forming as the sun rose. It would, over the next few hours, stretch around the corner and down the block.

Cigarette Pants

Scraps of History

One clothing retailer stubbornly remained downtown until the ground underneath became far more valuable than the business on it.

In 1926, Blumenthal’s got underway in a cubby hole at 358 South Elm. “The store with a heart” expanded into a new building built on that spot and adjoining properties in 1945 to create an 8,140 square-foot footprint specializing in denim jeans, work boots and hunting knives. Big and tall with extra, extra large sizes — a huge pair of bib overalls often on display to everyone’s amazement — could be found inside. Plus, they peddled cigarettes at prices so low, they were practically being given away just to get customers in the door. It worked. With 60 brands on hand, Blumenthal’s sold more smokes than any 10 stores combined.

Stacks upon stacks of Wrangler and Levi’s jeans, and the easy availability of Converse sneakers made Blumenthal’s back-to-school central for generation after generation. Suspended from the ceiling were three gigantic neon accented metal signs promising a free dollar bill if your receipt was incorrect or a complimentary pack of smokes if any of the numbers on your receipt matched numbers inscribed on the sign.

I won’t say this place was déclassé, but, for a time, there was a loudspeaker that allowed Abe Blumenthal to admonish people who parked too long out in front of his store. Blumenthal’s relocated to West Market in 2005 and closed its doors for good seven years later. The original location was supplanted in 2012 by an apartment complex named after the store.

Fashion Flare

Scraps of History

Proprietor John Mitchell began folding shirts and assisting his father and his uncle at Mitchell’s Clothing across the street from the Cadillac dealership when he was 12-years old. He’s a spry 95 today. In business since 1939, John Mitchell bought the place in 1962. “I changed things,” he tells me. “We were selling work clothes, work shoes, but I went into high fashion and men’s dress clothes.” Mitchell’s clientele has traditionally been and remains about 80 percent African-American.

Sales went through the roof when Mitchell picked up on an emerging unisex fashion trend out of Europe via New York City: bell bottom pants. “Belk and Meyer’s had ‘em first,” Mitchell admits. “But they couldn’t sell ’em so they quit. A year or two later, I got big into bell bottoms.” That was around 1970, when flared legs suddenly became the hot, hip-hugging style for both men and women. “For a while I was the only store in Greensboro selling bell bottoms and the Tom Jones[-style] rayon shirts with big, wide collars and stack shoes with the high heel.”

Besides Stacy Adams’ Madison shoes and crisp dress shirts, Mitchell’s is known as the place in town to find funky chapeaus from Stetson, Kangol, and more obscure designers. “People come from all around the country to buy my hats,” he says. Does he have any polyester era bell bottoms or platform shoes still hanging around? “A guy came in from California looking for those things and he bought all those old fashioned shoes and men’s clothes.”

’Tis the season to be thankful. And everyone knows how much pressure there is to say just the right thing sitting with the fam ’round a turkey you’re praying you didn’t overcook. (On the plus side, the wishbone will be dry and ready to snap, just like you.) We’ve got ya covered with some suggestions to show off your attitude of

’Tis the season to be thankful. And everyone knows how much pressure there is to say just the right thing sitting with the fam ’round a turkey you’re praying you didn’t overcook. (On the plus side, the wishbone will be dry and ready to snap, just like you.) We’ve got ya covered with some suggestions to show off your attitude of  In 2018, I paid my respects to the former Miss Anne’s Tic Toc Lounge in Macon, Georgia. It was here, in his birthplace, where Richard Wayne Penniman, singular sensation and “Architect of Rock,” won the talent contest that rocketed him to fame.

In 2018, I paid my respects to the former Miss Anne’s Tic Toc Lounge in Macon, Georgia. It was here, in his birthplace, where Richard Wayne Penniman, singular sensation and “Architect of Rock,” won the talent contest that rocketed him to fame.  “Right now, we especially need winter coats,” says Ashley West,

“Right now, we especially need winter coats,” says Ashley West,