Out of the Woods

Out of the Woods

Three Team U.S.A. Olympians redefine themselves in the Gate City

By Cassie Bustamante

Photographs by Mark Wagoner

“Woods are not like other spaces . . . They make you feel small and confused and vulnerable, like a small child

lost in a crowd of strange legs . . . They are a vast, featureless nowhere. And they are alive.”

— Bill Bryson, from A Walk in the Woods

This month, the City of Light will be aglow with 10,500 athletes from all over the world competing in the 2024 Summer Olympics, plus an estimated 15 million visitors.

To say the world will be watching is an understatement. But who are these athletes — heroes for a glorified moment in time — after the paddles have been stowed, the Nikes unlaced and the skates hung up for the last time? We caught up with three local Team U.S.A. Olympians, including two gold medalists, to answer that question.

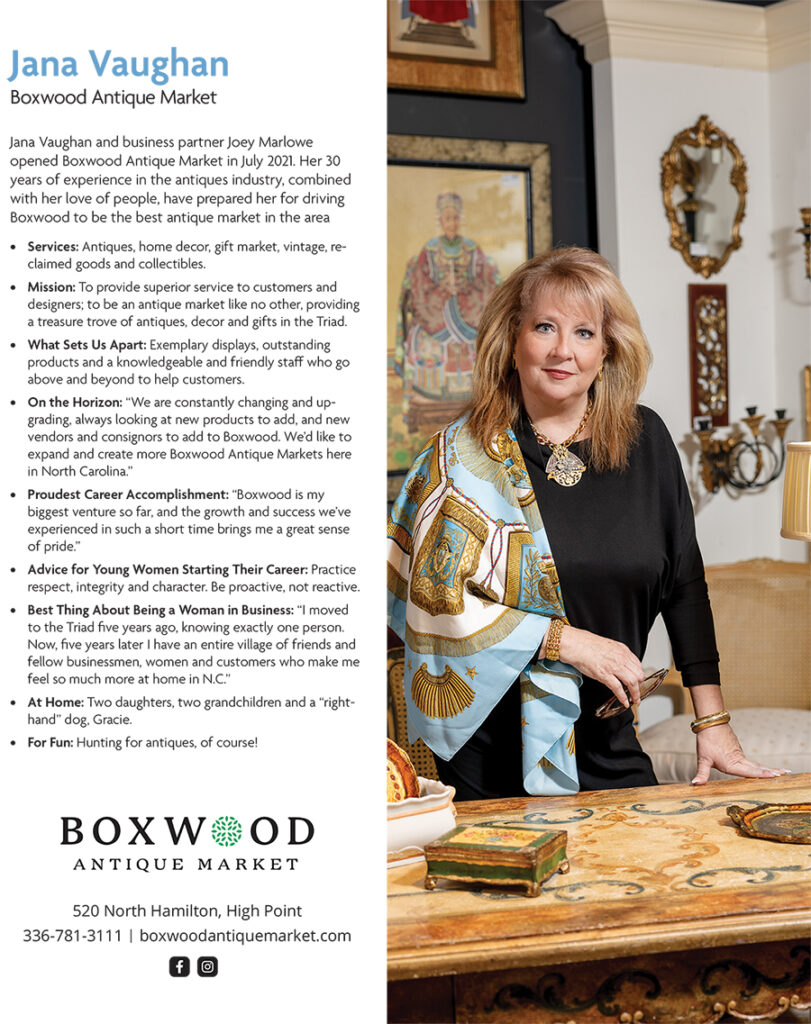

Joey Cheek, Gold Medal Olympic Speed Skater

Tamara Cheek, Olympic Canoeist

Sprawled out on his charcoal gray sofa, 2006 gold-medal Olympic speed skater Joey Cheek rests one hand on his chestnut-brown boxer, Cashew, who lets out a contented sigh. Both man and dog are totally at ease in this snapshot of daily life. But, Joey, now 45, admits that was not always the case for him.

“The years after the Olympics are — ,” he begins and then pauses. Tamara Cheek, also 45 and an Olympian herself, jumps in.

“Oh, are we at the walk in the woods?” After checking on Jack, the couple’s 4-year-old son, who’s happily scooting his Paw Patrol vehicles across the floor of the nearby playroom, she explains.

A Walk in the Woods, Bill Bryson’s New York Times-bestselling book about his ups and downs — both literately and figuratively — along the Appalachian trail, is a metaphor for how the Cheeks and some of their fellow Olympians describe life after the games. One reviewer called Bryson’s trek “A journey of discovery and renewal.” And that’s certainly been true for both Tamara and Joey.

For Joey, the path to the Olympics began when he was a roller-blading middle-schooler in Greensboro. His parents made sacrifices to support his fledgling athletic career. He recalls a home with sparse furniture and beat-up cars. “I had everything I needed, which was also all I ever wanted.” At 16, he left home to train in Calgary and made the leap from wheels to blades.

In 2002, 22-year-old Joey made it to the Salt Lake City Olympic Games, where he won the bronze medal in the 1,000-meter speed-skating event. Four years later he returned to the Olympic rink, this time in Turin, Italy.

As he headed back, he had an inkling that this would be his last time skating on Olympic ice. Plus, he wondered, “What am I going to get from four more years of this that I haven’t already gotten?” Turns out, that thing was a gold medal — as well as a silver.

Without taking a pause, he hung the skates and hit the ground running, enrolling in Princeton and cofounding Team Darfur to raise awareness about the ethnic cleansing and genocide in Sudan. His humanitarian activism caught the eye of Hollywood star George Clooney, who invited Joey to accompany him to China via private jet to lobby the government there. In 2007, Clooney reached back out to invite him to be in a film he was shooting in South Carolina. “And to give you an idea of the hubris I was feeling at the time,” says Joey, shaking his head, “I said, ‘I’ve got a bunch of big parties I am going to. I can’t make it.’”

He was seemingly skating through life. “Nothing is indicating that this system isn’t flawless,” says Joey, “that you have not cracked it.”

The path was clear: “gold medal, ivy league, billionaire.” Upon graduation, he was off to New York City to launch a sports-streaming start-up.

But, for the first time in his life, “some of the wheels had started falling off,” he says. “And that was crippling for me. Crippling.”

So how did he get out of the woods? “A huge part of it is her,” he says, looking at his wife.

“She had me do this exercise,” he says. Tamara helped him analyze his life up to that point so that he could see the arc of his career — which, he notes, was worse than ever at that moment.

But, soon after, “the arc turned.” He adds, “And it’s only gotten better.”

Did Tamara know from her own experience? Did she have a moment of “who I am without this?” she asks, then answers. “Yeah.”

But, Tamara admits, her moment of truth was not nearly as challenging as Joey’s. Hers came when a a friend who was a philosophy major at the University of California in San Diego (where she enrolled after the Olympics) pointed out to her that when you are young, you look to institutions to assign meaning to yourself. But once you leave academia — or the Olympics — and enter the real world, you’re on your own, and meaning and purpose must be generated internally.

“You might feel a little bit lost,” she admits and, as a mom of a superhero-loving preschooler, likens it to being Bruce Wayne instead of Batman. But, in the end, what was crippling for Joey was liberating for her.

Tamara is a dark-haired beauty who bears resemblance to — and has been mistaken for — supermodel Linda Evangelista. In fact, she opens to a page in her scrapbook, a gift a best friend created for a birthday, to a torn-out page from a 2000 Esquire magazine story, titled “The Girls of Summer.” Among 10 female Summer Olympians headed to Sydney, Australia, there’s an image of then 21-year-old Tamara, strong and tanned, and wearing a white tankini as she stands in a kayak and holds a paddle in her right hand. “I definitely shunned any further movement in that direction,” she says of her short-lived modeling gig.

Where Joey says that part of the reason you strive for the Olympics is to “chisel your name on a tablet somewhere,” Tamara’s approach as a flat-water canoeist was quite different. “I didn’t really have a gold medal as a goal ever.” She adds, “I just wanted to win races.”

Until she picked up paddles, competition was a foreign concept to Tamara. She describes the progressive Waldorf school she attended as the kind of place where “no blade of grass should be taller than the next.” But, at the age of 16, Tamara recalls seeing kayakers on a lake in Seattle, where she grew up. Instantly drawn to the beauty of the sport, she quickly discovered she took to it like a fish to water.

In another photo album, she opens to an old black-and-white photo of an athletic young woman, her grandmother, who died at the age of 36. She wonders aloud if that’s where her own inherent talent comes from. “I like to think that in some way I was carrying on her spirit when I was in Sydney.”

But, according to Joey, Tamara’s superpower is her ability to pick up anything she sets her mind to and excel. He laughs and adds how it sometimes drives him nuts “because there seems to be no method and all I am is process.”

While Tamara won the U.S. Olympic trials in the K-2 500-meter sprint as well as the 1999 World Cup silver medal in the K-2 1,000-meter kayak sprint, she did not land on the podium in Sydney and decided to leave her career as a canoeist after just six years. She admits that she was likely only halfway up the arc, but she was ready to move on. “I wanted to go to school and have a life after the Olympics.”

During college, Tamara continued to work closely with Team U.S.A. Canoe/Kayak, which was temporarily without a coach. Testing the waters of her own coaching skills, she filled in, discovering it was not the job for her.

Upon graduation, she was offered a role as a marketing director in Charlotte, working for the National Governing Body for Olympic Canoe/Kayak. While in that position, she also founded her own company — a platform-that connects creative service providers with real estate professionals — directed an award winning documentary and continued to serve the Olympic movement in professional and volunteer capacities. But her favorite career moment? Being on the team that won the rights to bring the 2028 Summer Games back to the states.

It was in Charlotte, says Tamara, “where our story begins.”

Her boss, late businessman David Yarborough, who became a mentor to her, asked her to attend a speech that Joey was giving. “For some reason, I didn’t go,” she adds.

But the “subconscious seed,” as Joey calls it, was planted.

Their stars were in orbit, says Tamara.

“Circling and never knowing each other,” adds Joey.

“You can’t fight fate,” he says.

Their stars would finally collide when both were in their upper 30s and involved with the Olympic Alumni Association, now the U.S. Olympians and Paralympians Association.

On January 1, 2019, Tamara, dressed in a white puffy jacket, and Joey, in the matching black, said “I do” atop snowy Lookout Mountain in Colorado, where they lived at the time. A year-and-a-half later, Jack was born amidst a global pandemic. Eventually, in 2021, with Joey working remotely for a venture firm he’d cofounded, the family piled into their Jeep with their dog and most of their belongings and headed for Greensboro, Joey’s hometown. The plan was to stay until they figured out their next move.

But, as he looked around a room full of family, Cashew happily playing with his brother’s dog, he says it dawned on him: “We are not leaving!”

The couple settled into a home where Joey kept an office, but his work was making him miserable and costing precious time with family. “I left with no plan. And I do not do that,” says Joey.

Encouraged by Tamara, Joey headed to a Downtown Greensboro event to learn about upcoming projects.

“You hadn’t been out of your office for three years,” she says to Joey.

While at the event, Joey met Thompson co-founder and president Clifford Thompson, who, Joey says, “is very active in wanting to see a startup community here.” Things began to click into place. In October 2023, he became the Greensboro Chamber of Commerce’s executive vice president for entrepreneurship.

And while the role is still quite fresh, Joey has big dreams for his hometown. “I want to be able to take Jackie downtown and say, ‘Look what we did in this town.’”

As for Tamara, she’s currently doing consulting work with the N.C. Folk Fest and serving on the Miriam Brenner Children’s Museum gala committee. And her community here? “Maybe I like it so much because it feels a little bit like it was training for the Olympics, like everyone is on the same page, “ she says, “that we believe in this place and we mostly want the same things for it.”

Now that these two Olympic speedsters are no longer racing to win, they have time for family, friends, community involvement. A walk in the woods these days? It’s a Sunday family hike along one of Greensboro’s many trails. And while life with a preschooler offers its own set of challenges, Joey says, “I would trade the worst day hanging out with Jack over winning medals.” He pauses and takes it a step further. “I will trade one back if it would give me one more day with him.”

Middle: Johnson works with N.C. A&T student Shadajah Ballard

Right: Johnson chats with Olympic hopeful Daniel Roberts

Allen Johnson, Gold Medal Olympic Hurdler

At 53, Allen Johnson doesn’t look much different than he did when he crossed the 100-meter hurdle finish line at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, taking home gold for the United States. His head is clean shaven these days, but his 5’10” frame remains slender and athletic. Sitting behind his desk at N.C. A&T State University’s Truist Stadium, where he has worked as director of the track and field programs since June 2022, Johnson is at ease, comfortable in his navy-blue Nike A&T-branded polo shirt and proverbial coach’s hat.

Is this where he imagined he’d be? No way. As an Olympic athlete training with coaching legend Curtis Frye, Johnson says that was not the life he envisioned for himself. “Being a college coach in track and field was the absolute last thing on Earth I wanted to do. I mean last thing.” Driving it home, he adds, “Last, last, last!”

But when his body could no longer achieve previous heights, Johnson had to take his own walk in the woods. “A part of you dies and you have to mourn it.”

As a young man entering UNC-Chapel Hill in 1989, Johnson, a D.C. native, assumed he’d major in business. “It was the ’80s,” he says with a laugh. “I wanted to get a BMW, big house, have money, live life.” His dream? His own car dealership. “I was always into cars,” says Johnson, who now drives a Tesla.

But his athleticism opened doors for him and he left Chapel Hill during his senior year, not before setting several school records that still stand as well as winning four ACC titles. (He went back to finish his degree, which he earned in sociology, in 2012, when daughter Tristine was an undergrad. He even had a class with her.) Johnson’s pursuit paid off with a full-time track and field career that spanned 17 years, from 1993 until 2010.

During that time, Johnson, participated in three Olympics: 1996 in Atlanta, where he won the gold; 2000 in Sydney, Australia, where he fought a hamstring injury and just missed the podium, placing fourth; and 2004 in Athens, Greece, where he was captain of the U.S.A. Track and Field Team but did not place. For most of that time, he had endorsements from Nike (1994, 1996–2008) and Oakley (1995–2004) to support him. But, he says, “The last two years I was kind of on my own.”

“I was going to run until the wheels fell off, which meant I was going to stay too long,” he says, confessing he ran two years too long. “In a perfect world, I would just love to get up in the morning every day and go race.” But, he admits, his body could no longer physically handle the work.

In 2008, just two years before his running career crossed its finish line, Johnson recalls seeing Marion Jones on Oprah, discussing her use of illegal performance-enhancing drugs. Jones likened being an elite athlete to wearing a mask, playing a part. And when those running days are over? “The mask has to come off,” says Johnson.

“You don’t feel invincible, emotionally — or anything — because you become a regular person again.”

But, he adds, “you’re reborn.”

For Johnson, an opportunity to become something new was found in the last, last, last place he ever expected.

It began organically. People came to him, seeking his expertise and offering to pay. He volunteered as assistant under Coach Frye at the University of South Carolina. “I never got paid, but I looked forward to getting up and going out there the next day to work with the people I was working with.”

In the fall of 2011, he was offered a paid position as assistant coach at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. He was nervous. Not only was it something he hadn’t done professionally, but it was far from the Mid-Atlantic states he’d called home for most of his life.

“That was a leap,” he says. But without risk there’s no reward. During his first year there, he led the 4×400-meter relay team to the Mountain West titles. He stayed there for five years before returning to the East Coast as assistant coach for the N.C. State Wolfpack, where he worked for six years.

While not every athlete makes a great coach, Johnson seems to have cracked the code. “You know the whole cliché, meet them where they are,” he says.

That doesn’t mean just physically. Johnson connects with his athletes on an emotional level, too. He looks for triggers, good and bad, creating strategies to handle those that arise. He helps them stay away from the negative while embracing the positive. Plus, he makes himself available. “I have a policy: If you need to talk to me, call me any time.” With a coy smile, he adds, “But try to keep it between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m.”

Now, in his first head coaching position at N.C. A&T, that policy’s expanded to include staff as well. “Be ready for anything” is his daily mantra. Emails and calls come from every which way, sun up to sun down and beyond. “One thing I tell people about being a college track and field coach is the job is never done. You just pick a stopping point each day.” And when he finally makes it home, he spends time with his wife, Olympic bronze-medal-winning track sprinter Torri Edwards-Johnson, and plays with their 2-and-a-half year old daughter.

While his days can be filled with chaos, he’s got a small network of friends who are also first-time head coaches, similar to having Olympic teammates. “We all have had aspirations of being a head coach and what we thought it was going to be like,” says Johnson. And is this it? No, he says, “You don’t know what it is until you actually do it.”

It’s challenging him in a new way. But he’s got sound advice when it comes to tough times: “It’s what you do on the bad days that is going to define your success.” He adds, “It’s not really that hard on a good day. It’s hard on the bad day when you don’t feel like doing it, but you dig down deep, mentally, physically, and you get it done.”

Are there moments he wishes he could be 25 again and line up with the athletes? Of course. “But I can’t do it anymore.”

Instead, he’s found joy in helping others. As for his student athletes, he wants to make sure their college experience is happy and meaningful, and that he pushes them to move the stopwatch needle.

Plus, Johnson has been working with Olympic hopeful Daniel Roberts, who, like Johnson, is a 110-meter hurdler. Roberts won the bronze medal in the 2023 World Championships and Johnson’s goal this year is to get him the gold at the Paris Olympics later this month. “I wish I could still run — can’t — but getting to coach him, coach Trayvon [Bromell] and the other athletes, I guess for me it’s kind of a natural progression to the next phase.”

Is it the same as competing? No, Johnson admits. “But I have no regrets. I love track and field.” And while it’s the last thing he thought he’d be doing, turns out the next best thing is helping someone else reach their highest potential. OH

*At the time this story was written, Roberts was training with Johnson for the Olympic Trials, which were held June 21–June 30. We will update you on his progress in our biweekly newsletter, found at oheygreensboro.com.