Animal Tales

ANIMAL TALES

I Know Not Where I Go

Lessons from the lodge

By Eric Schaefer

An oriole sings to me from the top of a hickory, and I rush to put out orange slices and pots of grape jelly. But he won’t stay. Every spring, he flies off as if he has some important place to go. “Stay a while,” I say. “There is no hurry.” But he’s off to an unknown destination. I can’t stay much longer either.

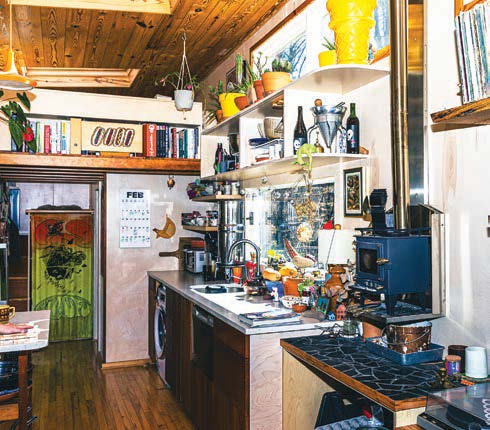

We bought the place because of the lake. The house was a wreck. We hauled out a dozen soiled mattresses, a pickup load of beer cans and various detritus. The work was hard, but there was always the lake. We took lots of breaks to lounge and try to find the cool places where the springs came up from the bottom. One day, an engineer from the state came around and inspected the dam. He said the trees on the back side of the dam should not have been allowed to grow up. Their roots would undermine the dam’s integrity, but cutting them down now might be worse because rotting roots were more dangerous. Telling us what should have happened before we arrived was not helpful, but he was right. The dam grew weaker and more vulnerable each year but held on until the remnants of a hurricane backed up water, and it gave up in a sudden, catastrophic collapse. Three acres of water, fish, turtles and flotsam went downstream overnight. In the morning, there was nothing but mud.

Since fixing the dam was prohibitively expensive, we were forced to watch nature reclaim the land. Initially, it was depressing, but nature didn’t waste time providing us with a show. Grasses and shrubs were quick to sprout, and it wasn’t long before willows, sycamores and sweet gums covered the old lake bed. We traded kingfishers and hooded mergansers for common yellow throats and a chat or two who liked the new growth. Then, one morning, walking the stream that runs down the middle of the old lake bed, I came across a stick that had been stripped of its bark.

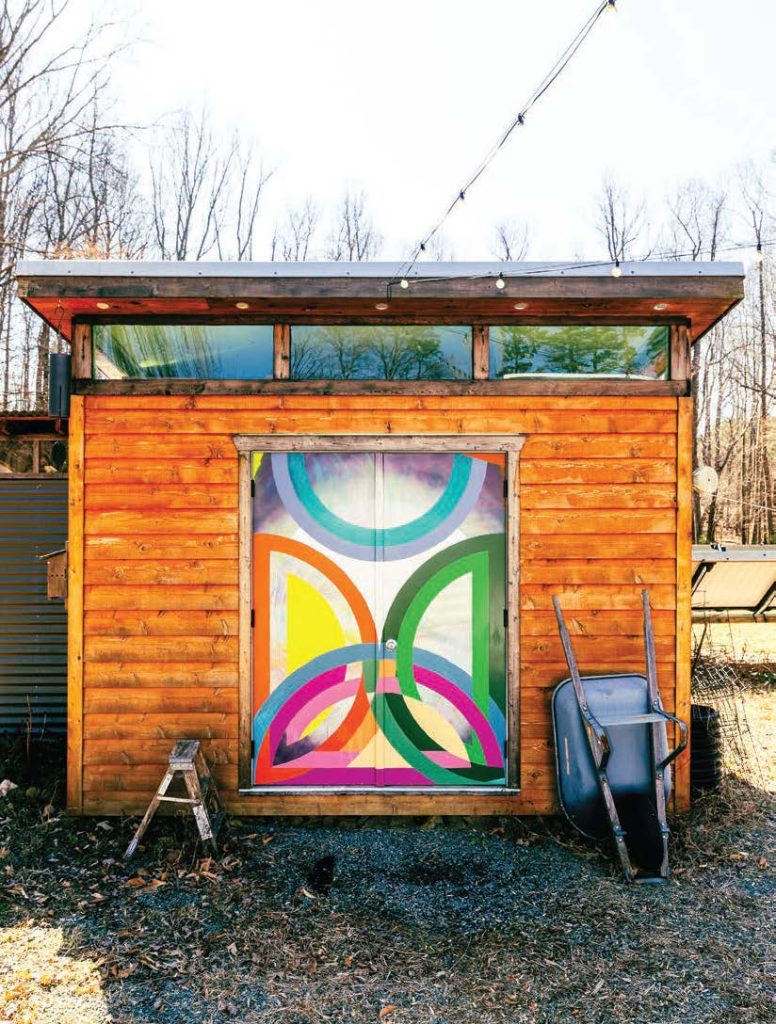

Beavers are often considered a nuisance, but, in my old lake bed, they were welcome. It took them just a few days to construct their first dam. While working, they lived in a burrow in the stream bank and came out to work crepuscularly. I thought their first dam should have been located further downstream, but my wife said, “Don’t argue with the engineers. They’ve been doing this for a long time.”

She’s right. Castor canadensis has been shaping the landscape for 7 million years or so. They not only build dams and lodges, but, once water backs up enough, they dredge channels in their new pond so they can swim deep enough to keep out of reach of predators. When they cut down a tree that is too big to drag, they either cut it up or make a canal to float the wood to where they want it.

I wanted to watch the endeavor, so I started going down to the stream early in the morning and evening. The first animal I encountered slapped his tail on the water hard enough to sound like a gunshot, making me nearly jump out of my boots. But I knew the pond wasn’t big enough for him to hide for long, so I sat down to wait. Sure enough, he stuck his nose out of the water in a minute or two. He lay motionless with just his nose above water, looking me over until he decided I wasn’t a threat, and then he glided across his pond to where there was a freshly cut willow branch. He sat on his haunches in the shallow water, held the stick in his front paws and started eating the bark off the stick like you would eat corn on the cob.

I began to visit him regularly in the evening. Sometimes, I’d bring a snack and eat with him. He never gave that warning tail slap again. He’d pause when I’d arrive — I fancy he was making sure it was only me — then he’d go about his business, unperturbed. Sometimes, a more petite beaver, perhaps his girlfriend, would show up. They built an impressive mound of sticks on the pond’s bank, and I could imagine its cozy interior, where I hoped they would be raising kits in the winter. Beavers are laid back about their accommodations. They have been known to share their lodge with otters, muskrats and other wetland neighbors. If I had been smaller and a little younger, I might have tried to visit them in their home.

Tragedy struck one day in the form of another storm that raised the water enough to wash away the beaver lodge and completely destroy their dam. I don’t know where they ended up; I haven’t seen them again. The lake bed is now filled with willow stabs and brambles. They didn’t like the sycamores much and left them pretty much alone, so the area has taken a new turn. I’d like to watch and see what develops, but my wife and I can’t take care of the place anymore. Can’t keep the house from falling down or the yard from turning into a jungle. We can’t keep enough wood to keep the fire going. We’ll be moving on soon. I know not where, but there will be a different assortment of birds, perhaps an unfamiliar flowering shrub might catch my eye, or a butterfly new to me will land on the bench where I’ve come to sit and watch. I might even land where the oriole makes his home.