Murals, Music, Museums

MURALS, MUSIC, MUSEUMS

Murals, Music, Museums

Exploring Elkin,one of North Carolina’s underrated destinations

By Danielle Rotella Adams

Winding down the sloped, two-lane road into downtown Elkin, the Blue Ridge Mountain majesty emerges as an unexpected backdrop. On a clear, sunny Friday, my husband, Tom, and I travel past grand, centuries-old Victorian homes that line the streets. Sprinkled among them are charming, 100-year-old Craftsman-style bungalows with intricate stained-glass doors and wide, red brick columns. It’s easy to imagine neighbors visiting each other’s porches, drinking fresh-brewed sweet tea on blistering summer days.

Just 65 miles from Greensboro, Elkin offers a slower pace where history and creativity are a way of life.

As we slow down to park, an enormous mural serves as a sort of welcome sign. Chapel Hill artist Michael Brown, whose work can be found locally at the Greensboro Public Library’s rotunda, has painted a landscape of perfectly lined grape vines set against Stone Mountain and a cloudy, Carolina-blue sky in the background. Business owners in Elkin have been adding their own murals to the blank sides of their buildings since 2012 as part of the Mural Grant Program, bringing a bit of whimsy to the “Best Little Town in North Carolina,” a slogan dating back at least 100 years.

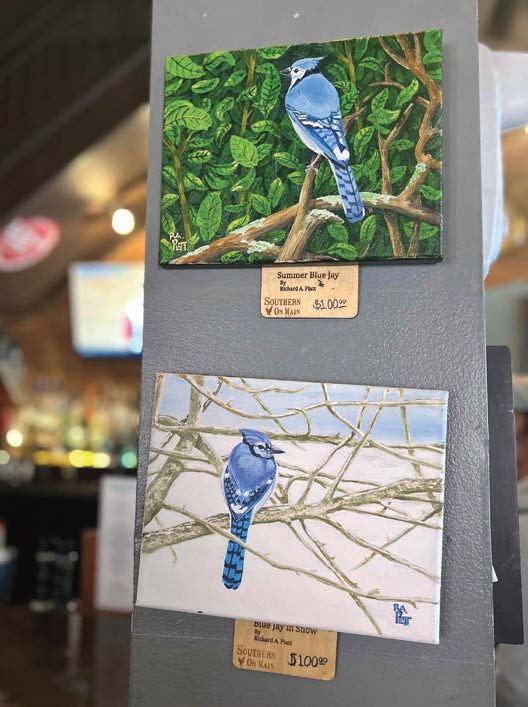

Arriving at lunchtime finds us ducking into a scrumptious farm-to-table feast at Southern on Main, a hometown favorite that proudly displays art for sale. Vibrant bluejay canvases pop against the wood-beamed walls.

Marvin Gaye’s “Take This Heart of Mine” plays faintly in the background as our cheery waiter, Dennis, reaches our corner patio table, holding a tray of starters — hot bubbling Gouda mac-and-cheese, tangy, crisped-to-perfection Brussels sprouts, and creamy deviled eggs. His eyebrows inch up when we decide to pile on the enticing blackened catfish and chicken pot pie. Our bellies filled with Chef Marla Egger’s seasonal, Southern fare, we set off to see what else Elkin offers.

Walking past an old train car, we soon arrive at the Yadkin Valley Heritage & Trails Visitor Center at 257 Standard St. Another massive Michael Brown work highlights the story of the Revolutionary War’s Overmountain Men, who crossed the Yadkin River on their way to King’s Mountain, S.C. Inside, we learn how far back Elkin’s history goes, back to when Sioux Indians settled along the Yadkin River as early as 500 B.C.

Next, we trudge up steep Church Street to admire the quaint Richard Gwyn Museum at 139 Church St., built in 1850 by Gwyn himself, Elkin’s founder. Although closed, we peek inside the tiny, wooden one-room schoolhouse, where a single teacher educated children of all ages and grades together.

Gwyn established the town’s first and most influential industries — a gristmill and a cotton mill, later sold to the Chatham family. The Chatham Manufacturing Company started producing wool Civil War uniforms, blankets for soldiers in World Wars I and II, and, later, car upholstery.

History, check. Next up? Shopping! We head back to Main Street, where flowering perennials and annuals spill out of the tops of oak barrels carefully placed on street corners, featuring handwritten directional signposts to help visitors find local spots. Suddenly, we realize that we’re trekking down the Mountains-to-Sea Trail (MST), a small segment of the footpath that stretches almost 1,200 miles across North Carolina.

Walking into Wildflower DIY Bar makes me smile. Owner Laura Wood sits at a large table surrounded by assorted paints, probably studying her next project. She opened Wildflower more than 10 years ago and migrated to different locations before landing at her 111 W. Main St. spot, where she teaches classes, hosts parties and sells local paintings, beading, and handmade whimsical creations. A self-taught artist, Wood grew up in Elkin and worked in mental health, where she found that her students with disabilities discovered their inner beauty through art. She now helps others find their creativity in a myriad of ways.

“There’s a lot of art, culture and history in Elkin,” Wood shares. “Everyone knows everyone, too, and if you need something, someone will help you out.”

Continuing down the main drag, we pass Michelle’s Consignments and Yadkin Valley Fiber Center, before stepping into Candles Etc. As indulgent, floral fragrances fill my nostrils, owner Kerri Ramsey greets us near the door, sharing how her Earth-friendly, soy candles are all hand-poured on site. She opened her shop in 2024, but sold candles before then at nearby wineries, where she also offers onsite candle-making classes. No way I’m leaving empty-handed. I load up with an Elkin Rainstorm candle, glass matchstick holder, and “Take a Hike!”-etched candles. Ramsey then shows me her favorite seasonal selection, so I pile on Holly Jolly Gingerbread and Cranberry Spice candles. Fall is just around the corner, after all.

On the other side of Main Street, we tour Demo’s Art Loft, located inside Kennedy Auto Antique Shop. Walking into the antique shop feels like stepping back in time, merchandise stretching as far as the eye can see, possibly from all the decades the shop has existed — seven, to be exact. After meeting Maggie May, the owner’s long-haired dachshund and obviously the store’s security detail, I walk upstairs to meet artist Geoffrey Walker and leave Tom downstairs to see if there are any nostalgic relics he can’t live without.

Walker, who opened his store in 2017, uses different mixed media, from graphite, ink and watercolor to 2D and 3D printing and woodworking. He has a knack for landscapes, portraits and unique anime creations. After I buy three of his framed prints, he asks, “Do you want to see the phonographs downstairs?” Meeting Tom back at the main level, the three of us venture to the basement, where a treasure trove of beautiful, ornate, hand-cranked phonographs from the early 1900s awaits. Their intricate oak and mahogany cabinets are etched, some with decorative red roses and green vines.

“I learned by seeing what they do, trial and error, and talking with other people,” Walker happily remarks. “The spring,” he notes, “is the main thing that needs repair — it has fatigue over the years. Sometimes it’s a simple fix.”

Speaking of “fix,” the smell of freshly roasted coffee beans lures us into Milk & Honey Coffee Company on West Main Street for a subtle jolt of post-shopping caffeine. Opened in 2025 by baker Faith Stone and her coffee aficionado husband, Sam Stone, the shop’s ornate chalkboard menu offerings scratch our itch. More caffeinated specialties can be found at Garden Route Coffee, owned by Tina and Rod Poplin, former missionaries in South Africa who fell in love with local, high-quality coffee. After sipping on a delightfully creamy Honeybee Latte and noshing on a buttery, homemade Berry Pop Tart, we follow our ears to the downtown music scene.

We just so happen to stumble upon Friday Night Live at Reeves Theater, which brings live music to different spots downtown, April through October. Tonight, Couldn’t Be Happiers and Catastrophe Journal, both from Winston-Salem, fill the Art-Deco style movie house with indie-folk and indie-pop sounds. We order glasses of Shelton Vineyards Bin 17 Chardonnay from the theater bar and tap our feet to high-energy originals.

Opened in 1941, the 250-seat theater underwent several iterations before three devoted Elkin residents, Chris Groner, Debbie Carson and Erik Dahlager, turned it into a live music venue in 2013. Free Music Wednesday is offered year-round. The Martha Bassett Show records live every other Thursday, and ongoing jams can be enjoyed by The Reeves House Band.

Finally, our tummies are rumbling again, and we venture to Angry Troll Brewing, the town’s homegrown local microbrewery and restaurant. A renovated textile warehouse with tall, wood-beamed ceilings, exposed brick, and numerous TVs, we opt for a steaming-hot sausage pizza and garlic buffalo wings, washed down with Orange Goblin Ales. Despite its name, which is derived from the storybook troll whose bridge was demolished, Angry Troll has a warm, welcoming vibe. We can’t help but sing along with the ’90s tunes.

Not ready to tap out quite yet, we visit Embers Eclectic Pub, another popular watering hole on West Main Street. The pub name is inspired by an Irish proverb about finding lasting love, which seems to have been attained by owners and marriage partners Dylan Hayward and Alexis Usko, who moved to Elkin in 2016 and opened their locally adored spot six years later.

After a full day, we’re asleep as soon as our heads hit the pillow at Three Trails Boutique Hotel, a renovated historic building with studios, one-, two-, and three-bedroom units, several accessible options, and a stunning rooftop patio overlooking downtown.

After grabbing a quick breakfast the next morning at the Elkin Farmers Market, we buckle up and begin our short drive back home, the grape tree mural fading in our rearview mirror. But it’s not goodbye for long — I’ve already marked my calendar for next month’s Yadkin Valley Pumpkin Festival.

Simple Life

SIMPLE LIFE

The Light in August

Catch it before it fades

By Jim Dodson

Most mornings before I begin writing (often in the dark before sunrise), I light a candle that sits on my desk.

Somehow, this small daily act of creating a wee flame gives me a sense of setting the day in motion and being “away” from the madding world before it wakes. I sometimes feel like a monk scribbling in a cave.

It could also be a divine hangover from early years spent serving as an acolyte at church, where I relished lighting the tapers amid the mingling scents of candle wax, furniture polish and old hymnals, a smell that I associated with people of faith in a world that forever hovered above the abyss.

According to one credible source, the word “light” is used more than 500 times in the Bible, throughout both Old and New Testaments. On day one of creation, according to Genesis, God “let there be light” and followed up His artistry on day four by introducing darkness, giving light even greater meaning. The Book of Isaiah talks about a savior being a “light unto the gentiles to bring salvation to the ends of the world.” Throughout the New Testament, Jesus is called the “Light of the world.”

But spiritual light is not exclusive to Christianity. In the Torah, light is the first thing God creates, meant to symbolize knowledge, enlightenment and God’s presence in the world. Surah 24 of the Quran, meanwhile, a lyrical stanza known as the “Verse of Light,” declares that God is the light of the heavens and the Earth, revealed like a glass lamp shining in the darkness, “illuminating the moon and stars.”

Religious symbolism aside, light is something most of us probably take for granted until we are stopped in our tracks, captivated by the stunning light show of a magnificent sunrise or sunset, a brief and ephemeral painting that vanishes before our eyes.

Sunlight makes sight possible, produces an endless supply of solar energy and can even kill a range of bacteria, including those that cause tetanus, anthrax and tuberculosis. A study from 2018 indicated rooms where sunlight enters throughout the day are significantly freer of germs than rooms kept in darkness.

The intense midday light of summer, on the other hand, is something I’ve never quite come to terms with. Many decades ago, during my first trip to Europe, I was fascinated (and quite pleased, to be honest) to discover that, in most Mediterranean countries, the blazing noonday sun brings life to a near standstill. Shops close and folks retreat to cooler quarters in order to rest, nap or pause for a midday meal of cheese and chilled fruit. I remember stepping into a zinc bar in Seville around noon and finding half the city’s cab drivers hunkered along the bar. The other half, I was informed, were catching z’s in their cabs in shaded alleyways. The city was at a complete, sun-mused halt.

The Spanish ritual of afternoon siesta seems entirely sensible to me (a confirmed post-lunch nap-taker) and is proof of Noel Coward’s timely admonition that “only mad dogs and Englishmen go out in the midday sun.” Spend a late summer week along the Costa del Sol and you can’t avoid running into partying Brits on holiday, most as red as boiled lobsters from too much sun.

In his raw and gothic 1932 novel, Light in August, a study of lost souls and violent individuals in a Depression-era Southern town, William Faulkner employs the imagery of light to illuminate marginalized people struggling to find both meaning and acceptance in the rigid fundamentalism of the Jim Crow South.

For years, critics have debated the title of the book, with most assuming it is a direct reference to a house fire at the story’s center.

The author begged to differ, however, finally clearing up the mystery: “In August in Mississippi,” he wrote, “there’s a few days somewhere about the middle of the month when suddenly there’s a foretaste of fall, it’s cool, there’s a lambence, a soft, a luminous quality to the light, as though it came not from just today but from back in the old classic times. It might have fauns and satyrs and the gods and — from Greece, from Olympus in it somewhere. It lasts just for a day or two, then it’s gone . . . the title reminded me of that time, of a luminosity older than our Christian civilization.”

I read Light in August in college and, frankly, didn’t much care for it, probably because, when it comes to Southern “lit” (a word that means illumination of a different sort), I’m far more attuned to the works of Reynolds Price and Walker Percy than those of the Sage of Yoknapatawpha County. By contrast, a wonderful book of recent vintage, Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, tells the moving story of a blind, French girl and young, German soldier whose starstruck paths cross in the brutality of World War II’s final days, a poignant tale shot through with images of metaphorical light in a world consumed by darkness.

But I think I understand what Faulkner was getting at. Somewhere about middle-way through August, as the long, hot hours of summer begin to slowly wane, sunlight takes a gentler slant on the landscape and thins out a bit, presaging summer’s end.

I witnessed this phenomenon powerfully during the two decades we lived on a forested coastal hill in Maine, where summers are generally brief and cool affairs, but also prone to punishing mid-season droughts. Many was the July day that I stood watering my parched garden, shaking my cosmic gardener’s fist at the stingy gods of the heavens, having given up simple prayers for rain.

On the plus side, almost overnight come mid-August, the temperatures turned noticeably cooler, often preceding a rainstorm that broke the drought.

When summer invariably turns off the spigot here in our neck of the Carolina woods, sometime around late June or early July, I still perform a mental tribal rain dance, hoping to conjure afternoon thunderstorms that boil up out of nowhere and dump enough rain to leave the ground briefly refreshed.

I’ve been fascinated by summer thunderstorms since I was a kid living in several small towns during my dad’s newspaper odyssey through the deep South. Under a dome of intense summer heat and sunlight, where “men’s collars wilted before nine in the morning” and “ladies bathed before noon,” to borrow Harper Lee’s famous description of mythical Maycomb, I learned to keep a sharp eye and ear out for darkening skies and the rumble of distant thunder.

I still gravitate to the porch whenever a thunderstorm looms, marveling at the power of nature to remind us of man’s puny place on this great, big, blue planet.

Such storms often leave glorious rainbows in their wake, supposedly a sign (as I long-ago learned in summer Bible School) of God’s promise to never again destroy the world with floods.

Science, meanwhile, explains that rainbows are produced when sunlight strikes raindrops at a precise angle, refracting a spectrum of primary colors.

Whichever reasoning you prefer, rainbows are pretty darn magical.

As the thinning light of August and the candle flame on my desk serve to remind me, the passing days of summer and its rainbows are ephemeral gifts that should awaken us to beauty and gratitude before they disappear.

Home Grown

HOME GROWN

The Long Game

Sticking our necks out to see African wildlife

By Cynthia Adams

My first trip to meet my new husband’s South African friends and family included days spent in Kruger National Park. “Park” sounds inadequate. It’s the size of Israel.

Upon arrival, park rangers handled admissions. Today, the 7,576-square-mile park’s entry fees translate to about $28. I can’t recall costs at the time, but it was easily half of that price. Tours are self- or ranger-guided, but we opted for self-guided, which fit our paltry budget.

The map, along with the ranger’s terse warnings, was free:

Enter at your own peril.

Stay in your car with the windows up.

If you ignore that advice, beware: There are a number of wild, hungry creatures roaming freely within the park that would enjoy dining on you.

Be assured, you are on your own.

With that, we drove right in. On our own. Car windows, barely cracked open, turned us into a pre-warmed hors d’oeuvre for the ravenous beasties lurking about.

Unlike most public attractions in the U.S. with a slew of warning signs and legal disclaimers, South Africans treated park-goers like adults, assuring you that you alone bear the consequences of your choices.

True fact: More than 12,000 warning and safety signs are posted at attraction entrances in Disney parks and resorts. Litigious Americans apparently require them.

We were to remain on our own until reaching one of the park’s intermittent compounds, where we could either camp in a tent or, with a reservation, stay in a small, thatched-roof bungalow (called a rondavel) available for reasonable cost.

The famous game park was home to all “big five” — lion, elephant, buffalo, rhino and leopard. And, of course, giraffes. We proceeded to find a watering hole where we hoped to spot a big beastie.

Speaking of water: Yes, you are warned at entry not to leave your car, but a day in a car without a potty break is impossible. And, at the time we visited, there were NO easily available restrooms. Just miles and miles of dirt roads. You seldom encountered humans along the way. But you just might find the road blocked by an elephant.

Possessing the bladder of a small child, eventually, I had to stop. Urgently, I summoned my husband to stand guard as I scanned the landscape, vitally aware that the greater number of the wild animals calling Kruger home were not altogether friendly.

Just after I dropped my shorts, he began waving wildly. Meanwhile, I heard nothing — no snapping of a twig, nor the padding of a paw. Thankfully, no snarling.

NOTHING but my own noisy flow.

My husband waved more frantically.

My heart stopped. But I was helpless in that moment.

He pointed madly behind me, mouthing something, and I was sure the lions we had been hoping to see since morning had instead found my white, shiny backside and were about to pounce on the snack I had witlessly offered up.

What an end, I thought, heart thundering. I’ll never live this down, which, actually, would have been true had I been eaten while relieving myself in a public game park.

Imagine the TV reports. Imagine the stern faces of the park rangers, wagging a finger.

Shakily turning, still crouching, I observed that there was no big cat behind me — but two giraffes. Their impossibly slender necks were turned, their lash-rimmed eyes fixated. On me.

Know this: These are enormous animals. It was hard to breathe, given two competing thoughts: relief, given they were not aggressive beasties, and fear they would bolt. But the giraffes stood noiselessly, observing me as if amused, before they pivoted, moving away. Let me re-emphasize this: soundlessly.

In a later trip to another South African public game park, we were again on the lookout for big cats when a group of giraffes came into view.

We stopped the car, admiring their balletic movements.

Then, without any ado, a female dropped her baby, giving birth where she stood, the calf dangling by the umbilical cord.

I imagine it is rare to witness the birth of a giraffe, but the mother seemed nonplussed. Within minutes, the calf seemed to find its wobbly footing and walked.

Inspired by this, we staked out another watering hole for hours, determined this was a harbinger; this time we might glimpse a big cat. Instead, what we encountered was a roving pack of peculiar wild canines also known as painted dogs.

The mangy-looking, elusive mongrels turned out to be an endangered species and highly protected for their rarity.

And rarely seen.

So help me.

“Tell us about the big game!” friends invariably asked when we returned. We raved about watching rhino. Elephants. Wildebeests. Impala. Springbok. Giraffe. And even unnerving encounters with green-and-black mambas. OK. So what if we didn’t see any lions? (Not then, nor on subsequent game park visits, FYI.)

And as their eyes widened, we dropped our biggest brag: wild dogs.

Like my trousers on that fateful day, their faces promptly fell.

Omnivorous Reader

OMNIVOROUS READER

The Untethering of Time

Finding the truths in historical fiction

By Anne Blythe

These days, as social media platforms and conflicting political rhetoric abound, it can be difficult to discern fact from fiction. It’s tempting to reflect on the past to try to understand what might be prologue.

Sometimes, though, the history that has been fed to us over time turns out to be pure fiction — or at least some version of it. Other times fiction is better able to get to the nitty-gritty truth. Historical fiction with its modern lens on days gone by can release the anchors of time and enhance a reader’s experience and understanding of the past in ways that non-fiction does not always accomplish.

Three North Carolina writers from this genre, to name a few, have taken a stab at blurring the lines between the invented and the real with new historical fiction that spans many decades, and in one case centuries.

Charlotte-based author Joy Callaway transports readers of her seventh book, The Star of Camp Greene: A Novel of WWI, far beyond the Queen City’s modern financial district and tree-lined neighborhoods back to 1918, when the U.S. Army had a training facility about a mile west of what is now Uptown.

Nell Joslin, a Raleigh lawyer turned writer, takes readers of her debut novel, Measure of Devotion, back to the Civil War era as she chronicles a mother’s harrowing journey from South Carolina, where she was a Union supporter, to the battleground regions of southeastern Tennessee to tend to her critically wounded son, who enlisted with Confederate troops in defiance of his parents’ wishes.

And Reidsville-based Valerie Nieman, a former newspaper reporter and editor turned prolific author, takes readers on a journey to ancient Scotland in Upon the Corner of the Moon in her imagined version of Macbeth’s childhood before he became King of Alba in 1040.

Though the books are very different, each was born from digging through historical documents, archives and histories of the time, as well as a bit of on-the-ground research.

Callaway’s main character, Calla Connelly, is based on the real-life vaudeville star Elsie Janis, a so-called “doughgirl” who sang, spun stories and cartwheeled across the stage for American troops on the Western Front. The Star of Camp Greene opens with Calla toughing her way through a performance in the makeshift Liberty Theatre tent at the North Carolina training camp. The soldiers gathered were all smiles until a pall was cast over her act by the news of deaths in the Flanders battlefields near Brussels.

Despite the push of men moving to the back of the tent to absorb the unwelcome announcement, Calla thought it was important to continue the entertainment, providing a crucial diversion during somber times. But her head hurt. Sweat soaked through her costume as heat flushed through her body before an icy cold set in. The Spanish flu was circulating around the world, claiming more lives than the overseas conflict for which Camp Greene was training soldiers.

Calla was bent on impressing the men enough that word would spread to Gen. John J. Pershing. In her mind, he would make the final decision whether or not she could join the team of performers who traveled overseas to entertain the troops — and thus honor the memory of the fiancé she had lost to the war there. But she couldn’t stop the spinning as she tried desperately to belt out lines from George M. Cohan’s “Over There.”

Stricken with the deadly influenza, Calla ends up in the hospital. While recuperating, she overhears a piece of classified military intelligence resulting in her confinement at the Charlotte camp, where she’s assigned a chaperone until further notice. While prevented from traveling to the front, it opens her to the possibility of new love and gives Callaway an opportunity to explore themes of patriotism and injustice.

Measure of Devotion also tells the story of a war era through a strong, compelling female character. Through vivid and immersive writing, Joslin uses the 36-year-old Susannah Shelburne to bring life to the story of mothers nursing wounded sons near Civil War battlefields.

Susannah, who grew up in Madison County, North Carolina, and her husband, Jacob, live in South Carolina, where they are opposed to slavery in the very land that is fighting to preserve it. Jacob’s family had owned slaves, but the thought of another person being nothing more than property appalled him. After inheriting Hawk, Jacob granted him his freedom and paid him to work for him. They also employed Letty, a character whose homespun wisdom, optimism and love adds a welcome layer to a tender and complicated story.

The Shelburnes’ son, Francis, joined the 6th South Carolina Volunteers in the early years of the war, and on Oct. 29, 1863, his parents receive a telegram letting them know that their son had been severely wounded by shrapnel near his hip joint. Susannah leaves her ailing husband and travels by rail to Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, with hopes of sparing Francis’ leg from amputation while nursing the 21-year-old back to health. He’s in a fevered state when she arrives.

Joslin adroitly and compassionately explores heady themes that divided the country more than 150 years ago, and the hardships and ravages of a nation at war with itself.

Nieman’s Upon the Corner of the Moon is book one of two that explores some of those same issues in 11th-century medieval Scotland. Rather than relying on William Shakespeare’s depiction of Macbeth, Nieman alternates her deeply researched tale of the budding powers of the Macbethian royal court through three voices — Macbeth, Gruach, who becomes his queen, and Lapwing, a fictional poet.

Separately, Macbeth and Gruach are spirited away from their parents to be fostered into adulthood during an era of constant warfare and the unending struggle for power. Nieman ladles up a dense, deeply reported version of these two well-known characters before they meet. We see Macbeth as an adolescent warrior in the making, and Gruach being groomed in Christian and pagan ways to be given away in marriage. Ultimately, what unfolds is a tale of legacy, power and fate.

These three books of historical fiction bring factual bits of the past to the present, leaving much to ponder about their truth.

Drawing Room

DRAWING ROOM

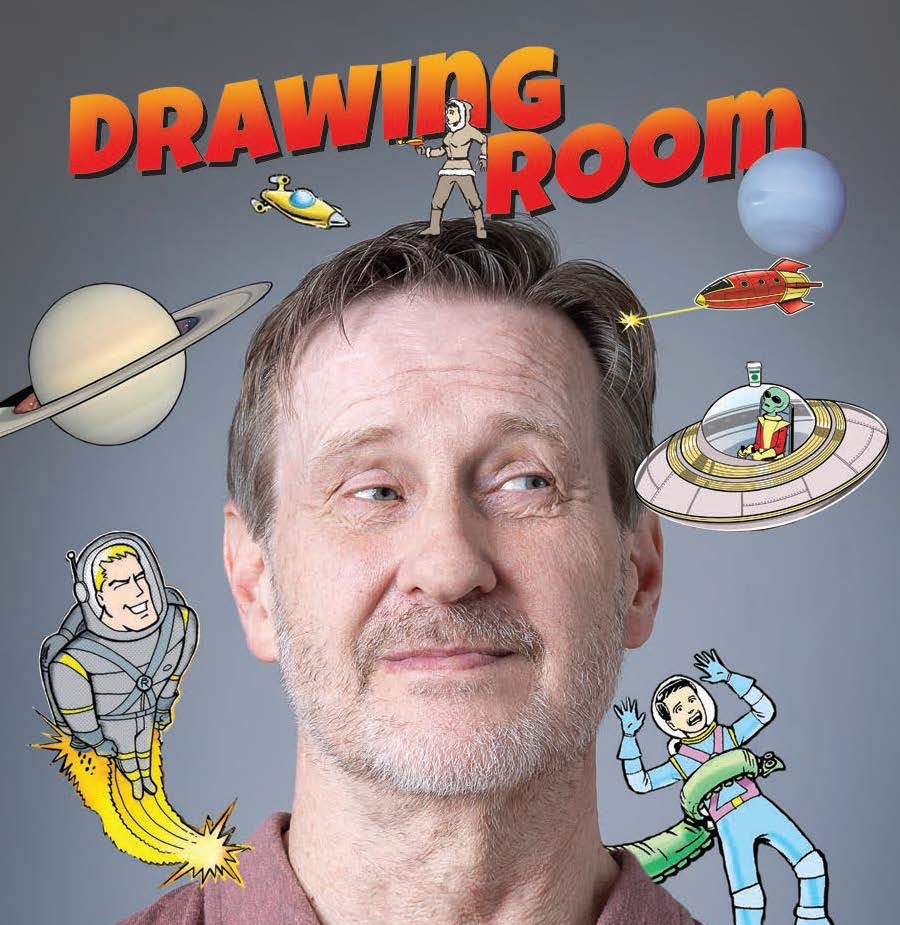

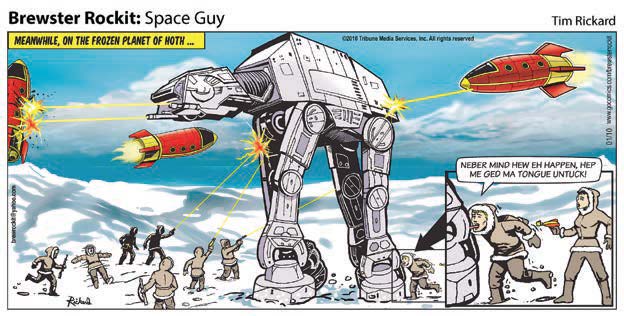

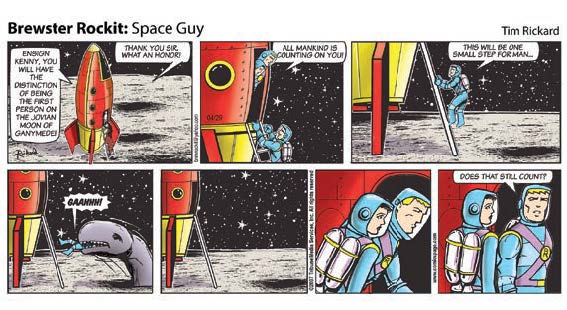

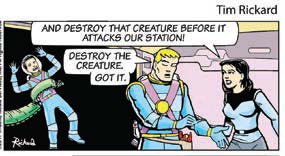

Greensboro cartoonist Tim Rickard reflects on two decades of Brewster Rockit

By Maria Johnson

Photograph by Bert VanderVeen

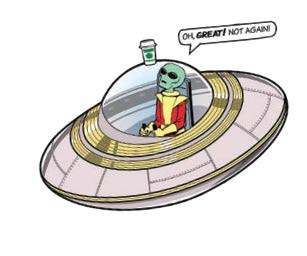

Someone sets a cup of coffee on the roof of their car.

They get distracted.

They drive off, cup still on top of the car.

This all-too-human scenario tickles cartoonist Tim Rickard as he picks up his stylus and starts doodling.

What tickles him more is the possibility of this uh-oh moment happening in outer space, specifically in the world he has created for his syndicated comic strip, Brewster Rockit: Space Guy!, which is named for its protagonist, the strikingly handsome and equally clueless commander of the space station R.U. Sirius.

In the 21 years since Brewster and his crew of cosmo-nuts first appeared in publications around the country, Rickard has blasted them into deep-space silliness thousands of times. He draws six strips a week: one for every weekday, plus a standalone for Sunday.

The strip appears in the funny pages of major publications, including The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune and the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

While Brewster is a tyke compared to some longstanding cartoons — Rickard’s broker, Tribune Content Agency, also represents stalwarts Dick Tracy, Broom-Hilda, Gasoline Alley and Annie — the commander’s longevity is a stellar achievement in the universe of syndicated strips, where the average feature lasts 10 to 15 years.

One key to Brewster’s endurance: a fan base that includes the professionally spaced-out.

“I love the way he manages to be informative and funny,” says Marc Rayman, the chief engineer for mission operations and science at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, CA.

He’s talking about Rickard, whom he credits with otherworldly talent.

Brewster is another story.

“Brewster never intends to be funny,” adds Rayman. “He’s not smart enough to be funny. But I admire his biceps and his jaw.”

Where would the ill-fated coffee cup be? Rickard wonders how to transport the commuter gag into Brewster’s world.

He sits at a desk in his home office, where he has worked since 2020, when he was laid off by Greensboro’s News & Record newspaper after 27 years as a staff artist.

He slides a stylus across a graphics tablet.

Lines appear on the 24-inch screen in front of him.

He roughs out the R.U. Sirius and places a coffee cup on top of the space station.

Nah, he decides. The cup is too small relative to the station.

Rickard, who resembles a salt-and-pepper version of the boyish Brewster, deletes the scene and starts over.

He draws a pointy-nosed rocket zipping sideways through space and outlines a coffee cup on top.

Nope. Still not right. Delete.

His mind and his hand keep moving.

He was a scribbler.

You know the one: The kid who draws on every napkin. Every flyleaf. Every sidewalk.

Rickard’s dad liked to tell the story of going into an Owensboro, Ky., cafe in the wintertime and watching his son, then 4 or 5, draw with his finger on the steamy windows.

Rickard, 66, who has been a member of MENSA, the high-IQ club, for about 40 years, looks back on his younger self with a mixture of humor and compassion.

Several years ago, he says, he realized that he’s probably on the high-functioning end of the autism spectrum, along with many others who excel in the visual arts.

As a youngster, he was plenty smart intellectually, but talking with people face-to-face was challenging. Communicating with pictures — with the chance to draw in solitude, erase and redo — was much easier.

He went to Kentucky Wesleyan College to study art, with an eye toward advertising. A couple of internships and freelance jobs later, he decided that working for a newspaper, on the editorial side, would offer more variety and freedom.

He joined his hometown paper, the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer. A couple of years later, seeking a bigger paycheck, he signed on with the News & Record. His portfolio expanded to include courtroom sketches, editorial cartoons and illustrations for stories that did not lend themselves to photographs.

He also started a weekly comic called Joke’s on You, a single-frame feature that showed characters in situations with no dialogue. Readers competed to provide the winning captions.

Summerfield veterinarian Tim Tribbett won 32 contests, more than anyone. One of Tribbett’s favorites showed a mama bear and baby bear gazing at a bearskin rug on the floor of their home.

“Couldn’t we just keep a photo on the mantle?” the cub asks in Tribbett’s caption.

Every week, Rickard sent the winner a signed, printed copy of their entry along with a note of congratulations. The strip provided a community for participants.

“We never met, but we felt like we knew Tim, and we knew each other a little bit,” says Tribbett.

When Rickard left the newspaper during COVID, about 20 faithful contestants threw him a party at a local park. They brought a cake topped with an edible image of Rickard’s work.

“The contest meant a lot to us,” Tribbett says.

Rickard is still pondering where to put the coffee cup.

Atop a small flying saucer?

That would be comparable to a car.

He sketches a small, sporty saucer with a clear dome. The coffee cup appears on top.

Bingo.

More questions blossom in his head: Who is inside the saucer? How many characters?

Is there dialogue between them?

Two aliens appear inside the bubble.

“You left your coffee on the roof again?” one says to the other.

Rickard studies the scene.

It’s OK.

But just OK.

Drawing a strip that appeared in funny pages nationwide — that was the goal.

Rickard started submitting ideas to syndicates when he was in high school.

Rejections piled up, but some contained a grain of encouragement.

“Not bad.”

“You’re a good gag writer.”

It was enough to keep him going.

He knew his ideas were derivative, hewing too closely to existing strips. He needed something fresh.

Long a fan of Star Trek, Star Wars, the Marvel catalog and monster movies, he was at home in fantasy worlds. But Earthly wisdom held that space-based comics didn’t fly, and Rickard was loath to try sci-funny until rejection pushed him to give it a whirl.

“I figured if I was gonna fail, I might as well fail doing something I want to do,” he says.

That’s when Brewster came to visit. Rickard was in his early 40s.

Drawing late at night while his family slept, he invited the hapless captain into his head to play. Soon, Brewster showed up with other characters, including Brewster’s very competent wife, Pamela Mae Snap; Dr. Mel Practice, the station’s crazed chief scientist, whose inventions include the Procrastination Ray; and Dirk Raider, a former member of Brewster’s Goodguy Knights who had crossed over to the sinister Microsith corporation.

Rickard drew his characters in a realistic style reminiscent of soapy comic strips Steve Canyon, Mary Worth and Rex Morgan M.D.

His concept — that Brewster and his goofy sidekicks protected the Earth from evil— was funny on its face, and it provided a lot of room for storylines.

In early 2003, Rickard sent samples of Brewster to three syndicates. Two replied with nays. The third did not respond. Rickard assumed that meant “no.” He let go of his dream.

A couple of months later, the third syndicate replied. They wanted to see more.

Rickard sharpened his strip according to the editors’ suggestions, and Brewster joined the fleet of Tribune comics in July 2004.

NASA’s Rayman saw the strip in the Los Angeles Times soon after it launched.

Brewster’s mix of scientific literacy and everyday nincompoopery impressed him and his real-world rocket scientist colleagues.

“Many of Tim’s comics — in fact, most of them — don’t have anything specifically to do with space,” Rayman says. “Like any creative artist, he uses the context he has created to cover many different subjects.”

Still, Rayman admits, he’s thrilled whenever Brewster mentions a mission that Rayman is actually working on, as happened in 2007, when the strip referred to DAWN, a probe that investigated the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Rayman contacted Rickard to suggest, in jest, that he should ask Brewster and crew for advice. Rickard was game. He incorporated Rayman and a legit question into a strip. Several characters offered lame words of wisdom.

Rickard and Rayman have been collaborating ever since. Rayman fact-checks some of the weekday strips, and they share responsibility for Rocket Science Sunday, an occasional educational version of Brewster.

“He’s extremely open to my comments and feedback,” says Rayman. “There’s no ego to hold back the quality.”

Or the buffoonery.

In Brewster’s world, Earthlings can escape gravity but not their foibles.

“The strip never feels like it’s talking down to anybody because the characters are so flawed and stupid and lazy,” Rickard says. “The reader is always in on the joke.”

Ideas come from all directions: news, science, popular culture.

Sometimes, Rickard’s own life seeps into the frames. After he had his first colonoscopy, so did the character named OldBot.

Once, an enemy storm trooper asked his daughter for help with his phone — a copy and paste of Rickard asking his own daughters for technical assistance.

Also, Brewster made a list when Pam asked him to complete more than one task.

“That was literally a conversation with my wife and me,” Rickard says.

In 2010, he and his syndicators traveled to Hollywood to pitch an animated movie based on Brewster, who appeared in 150 markets at the time.

Nothing came of the meetings, but the comic kept cruising.

Last year, The GreenHill Center for NC Art included more than a dozen Brewster pieces in a show of science fiction works by artists statewide.

Rickard relished the sight of Brewster on the walls of the tony gallery.

“He seemed totally out of place,” he says, chuckling.

Where might Brewster materialize next?

Rickard shrugs. He’d like to do another best-of book. A 2007 paperback collection subtitled Closer Encounters of the Worst Kind is out of print but fetches healthy resale prices.

As for the daily offerings, Rickard repeats his industry’s biggest non-secret: newspapers and other traditional customers are dwindling. The News & Record dropped the strip after they laid off Rickard.

One day in the not-so-distant future, Rickard says, Brewster might cease to dwell on paper, his original home, and live only online. Already, the strip appears at gocomics.com, an internet-only repository of cartoons past and present.

In a way, a total shift to cyberspace would make cosmic — and comic — sense.

Rickard says Brewster and his creator are ready to adapt.

“It’s always been a forward-looking type of strip, so the fact that that would be the inevitable home for him would seem appropriate,” Rickard says.

He deletes one of the aliens in the flying saucer.

The one-liner, “You left your coffee on the roof again?” disappears, too.

Only the driver of the saucer remains.

Rickard re-draws the alien’s head. Now he looks up at the cup through the clear roof of the craft.

A thought bubble appears.

“Oh, no. Not again.”

Rickard sits back and puts his stylus down.

That works.

Wandering Billy

WANDERING BILLY

Justice Delayed…

Diving into the deep end of a 1950s-era poolside predicament

By Billy Ingram

“Ah, summer, what power you have to make us suffer and like it.” — Russell Baker

Seventy years ago, in the summer of ’55, a paddling of people numbering in the thousands, swimming-trunked with towels shoulder-slung and slathered in Sea & Ski, descended en masse for the opening day of the newly minted Lindley Park municipal swimming pool. It wasn’t long, however, before that above ground complex began making waves, awash in a clash of cultures that seemed to fall on waterlogged city leaders’ ears.

It’s one of our city’s loveliest and most serene neighborhoods, but, beginning in 1902 before any homes were ever conceived of there, Lindley Park was originally an amusement park, complete with a sprawling lake, casino, dance pavilion, 1,000-seat vaudeville theater, miniature railroad, electric fountain and a cozy cafe. Live entertainment consisted of a trapeze act, a spunky monkey and a chatty parrot who likely ended up as a curiosity in the basement level of Silver’s 5–10¢ and $1.00 Store on South Elm and Washington.

The city’s first public park was named after J. Van Lindley, whose nearby 1,000-plus-acre nursery, established around 1850, was likely one of the largest in the world, with some 1.5 million plants under cultivation. Lindley lent 60 acres of the eastern end of his property to the Greensboro Electric Company with a proviso that they establish an entertainment destination there to coincide with the 1902 debut of the Gate City’s first mass transit system.

For less than a dime, commuters could trolley from North Elm downtown to the farthest western stop on Spring Garden Street, destined for the enchanted land of Lindley Park, where they could spend the day boating, swimming and tightrope gawking. Propelled along rails embedded into brick-lined streets and powered by overhead electrical wiring, a fleet of streetcars criss-crossed the city north to Sunset Drive, south down Asheboro Street (now MLK Drive), and both east and west on Market.

After the amusement park closed in 1917, Lindley gifted that real estate and another parcel to the city with a caveat — that a spacious, refined community be established there, designed by preeminent Southern landscape architect Earl Sumner Draper, who was behind Charlotte’s Myers Park and High Point’s Emerywood, among other tony neighborhoods. The lake was reduced to a creek with landscaped banks, making it a 107-acre verdant centerpiece to surrounding homes, soon to be constructed in a wide array of architectural styles, favoring Craftsman and Colonial Revival.

Endeavoring to reintroduce recreation to Lindley Park in 1955, the city sunk $200,000 into a public swimming pool designed to accommodate up to 800 sun worshippers, with 10 wide lanes for competition swimming and a cutting-edge aquatic sport scoreboard. There was one other city-owned pool in Greensboro reserved for the Black community built in 1937, located at Windsor Recreation Center on Lee and Benbow streets. After two Black women, Dr. Ann Gist and Ms. J. Everett, were turned away from the Lindley facility in June of 1957, the NAACP petitioned the city to integrate the pools.

Council members and apparatchiks such as Parks and Recreation commissioner Dr. R. M. Taliaferro voiced opposition to any attempt to abrogate the Jim Crow status quo. Current in their minds was the wanton unrest that erupted just a few Junes ago when Atlanta and St. Louis incited white rioters after their swimming pools were integrated.

Facing a potential unruly undertow that city leaders were loath to be swallowed up by, their initial reaction was to nuke the pools, plow them under, before realizing that a legal loophole could serve as a flotation device. At that time, private entities were at liberty to discriminate indiscriminately, so it was resolved to offload these two chlorinated, all-of-a-sudden nuisances at auction, sold to the highest (like-minded) bidder, thereby surreptitiously preserving this pernicious practice. That brazen tactic triggered a preemptive lawsuit (Tonkins v. City of Greensboro) adjudicated downtown in the U.S. Middle District Court.

In May 1958, the court ruled in favor of the defendant but deferred dismissing the suit until 30 days after the sale of the pool “to give the plaintiffs an opportunity to show that the sale was not bona fide in the sense that there was collusion between the defendants and the successful bidder regarding the future use of the pool.” In other words, the plaintiff had a short window of time after the sale to prove it had actually been rigged by the city to enshrine segregation.

On June 3, 1958, J. Spencer Love purchased the “lake-sized” pool at Windsor Center, turning the operation over to David Morehead, executive secretary of the Hayes-Taylor YMCA. The Lindley Park aquatic center was acquired for $85,000 (only 3 years old, what a bargain!) by a hastily assembled coalition calling themselves Greensboro Pool Corporation, one of the organizers being none other than the aforementioned Dr. Taliaferro. No surprise, the Lindley pool would remain whites-only.

Did someone mention collusion? An appeal to Tonkins v. City of Greensboro was filed, one of the attorneys consulting on the case being future Supreme Court Justice and legendary Civil Rights leader Thurgood Marshall. Argued in January 1960, a ruling in March declared that the plaintiffs had not met their burden of proof. While recognizing that Taliaferro had openly opposed desegregating the property and was instrumental in setting up Greensboro Pool Corporation, the judge ruled, “he was a member of a nine-man commission, which serves in an advisory capacity only, legal authority [for the sale] being in the City Council of which he was not a member.”

In 1967, just as an expanding, yet-to-be-named, Wendover Avenue (a road that began as a wagon trail rut in 1753) was carving away some 25 acres of the district, the City of Greensboro reacquired the Lindley Park Pool, making it accessible to all. A year later, a new swimming pool replaced the three-decades-old hole at Windsor Center, which, today, is being reimagined as the Windsor Chavis Nocho Community Complex, a 65,000-square-foot facility with, among many other impressive amenities, a lap pool, lazy river and water slide.

Meanwhile, drowning under innumerable structural and mechanical quagmires, the Lindley Park Pool at 2914 Springwood Dr., now our city’s oldest, has been hung out to dry since 2023 but workers are resolute to rehydrate that concrete crate sometime this season.

Just this morning, I ventured out, hoping to uncover the one remaining remnant from Lindley Park’s initial 15 years as our nascent township’s sideshow. Not shy about wandering around, behind a hilltop home on Masonic Drive, I discovered a dollhouse-like, wooden women’s cabana with dual French doors that once sat lakeside.

Bracketing the neighborhood entryways off Spring Garden are matching stone monuments. Characterized by obelisks boldly asserting themselves where the amusement park’s mammoth arched gateways were positioned on either side of the lake, they were installed in 1924, when Earl Sumner Draper’s master plan was nearing completion. Over a century later, those monuments still warmly welcome visitors and residents alike to a shady little lady known as Lindley Park.

The Gentlewoman and Happy Farmer

THE GENTLEWOMAN AND HAPPY FARMER

The Gentlewoman and Happy Farmer

Margie Benbow bought the farm

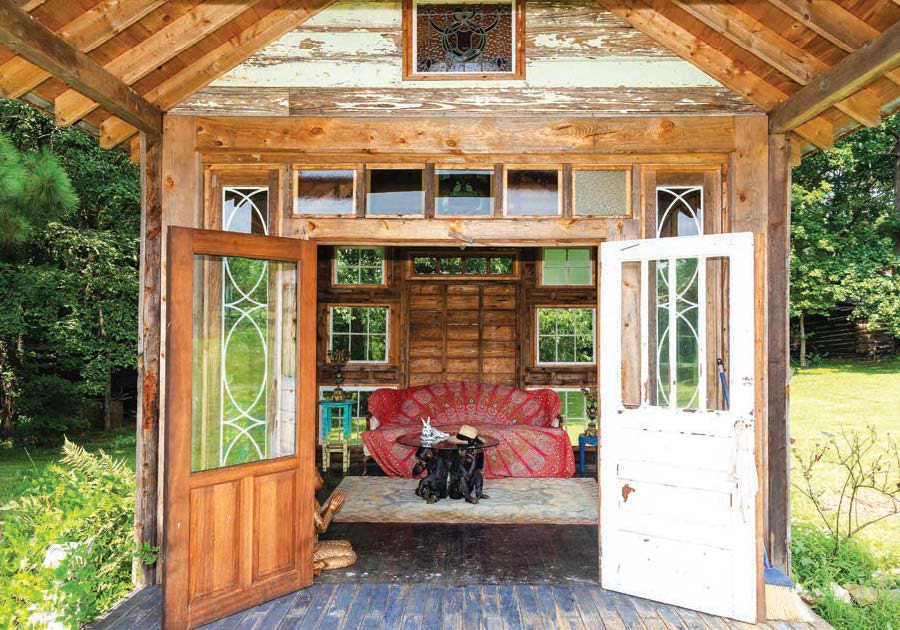

By Cynthia Adams • Photographs by John Gessner

Margie Benbow did not grow up on a farm. But the easygoing former urbanite says, “I wanted to be a ‘country’ Benbow.”

And so she is, living contentedly in a traditional, white clapboard farmhouse nearing a century old. One with generous porches and a wide-open view to acreage planted in fescue and flowers.

Wearing a denim dress with overall straps, Crocs sandals and a red bandana holding back her blond hair, you might guess she has known nothing but life on a Summerfield farm. But you’d be wrong. She is a scientist, lawyer, auctioneer and artist — now farmer — joining the ranks of 24,160 women farmers in North Carolina, where the percentage of women jumped 90% in recent decades.

She’s downright Jeffersonian in her wide-ranging ambitions, not only practicing law while farming, but simultaneously making a serious run at political life last year. No matter that she lost her race for the North Carolina House of Representatives; Benbow maintains a natural sunniness, a goodwill that makes even her losses look like wins.

This is decidedly her super power.

If any of her dreams were easy, she probably wouldn’t even have found them very interesting.

Nine years ago, Benbow said goodbye to the din of traffic and all that comes with it, having lost her physician husband, Dr. Hector Henry, to cancer. Court dockets no longer ruled her calendar — just before the pandemic, she had settled into a rural rhythm largely dictated by Mother Nature.

She acquired not one, but two farms — another is a leafy drive away in the tiny community of Bethany, population 362.

Summerfield, by comparison, is practically a bustling suburb of over 11,000 residents. This, she laughs, is her city residence.

Wandering into the kitchen to prepare a ginger tea, Benbow appraises the space, which is open and oriented to the farmland behind the house. Even inside, she can keep watch on her crops from the dining room table.

She came of age in a pleasant Winston-Salem neighborhood as a “city” Benbow, with three sisters and a brother, relishing visits with the family’s “country” kin. She confides having always envied the life of her counterparts.

She ruminates about the reasons she is smitten with being far from the maddening horde.

“They had a pond. Since I was 4, I’ve wanted this life,” she declares.

Now she, too, has a pond of her own at the Bethany farm near a log cabin where restoration is underway. As further proof of self-reliance, Benbow has tasked herself with learning to make a split-bamboo fly rod — should she ever want to cast off. Online tutorials are daunting. But, then, that probably just whetted her appetite to learn.

In Summerfield, she has created a sunny, happy haven, the rooms dominated by whimsical, colorful art.

“This is my city house,” she teases, nary a neighboring house in sight. “My country house is 4 miles down the road.” She first bought the Summerfield house and 20-acre farm in 2016. The second farm, bought in 2020, sold at auction. Benbow was the top bidder. Land, she explains, is an addiction.

Then, the pandemic struck and a lockdown ensued. She realized she was going to have more than a small amount of isolation, even in what she calls her “city” house because of its proximity to Summerfield. She admittedly binge-watched Netflix and ate popcorn.

But also, she got busy.

As an avid artist, Benbow weighed the overall aesthetics of the house where she had moved. “It had amazing bones.” The kitchen, centrally located and serviceable, made sense to leave much as she found it, preserving the existing layout. The space includes four sets of doors making it light-struck and airy.

But Benbow explains that the farmhouse was a less daunting project than the restoration of the farmlands whereupon it sits. Much had already been accomplished in the house when she acquired the property, she says. Essentials, like replacing windows. But some things were neglected, like the disintegrating fireplace bricks.

Then she considered ways she could inject her own style. The cosmetics could use some help, she decided. Benbow ripped out the kitchen tile, designing and crafting her own backsplash tile at the Sawtooth Center in Winston-Salem. A hefty butcher’s block, repurposed as an island, required six people to move in as well as joist reinforcement. But once in place, it looked as if had always been there.

The open kitchen, now suitable for a serious cook, features a professional range. But when questioned about cooking, she laughs. “It looks like a cook’s kitchen.”

Cooking? Not her thing.

Benbow points out the most-used “fancy” appliances, giving a throaty laugh: a toaster, a popcorn popper, a Ninja juicer and a coffeemaker.

“That’s about it.” Still, she agrees. The range looks great.

As a rule, where Benbow found original farmhouse details, she kept them. But the ugly and unoriginal popcorn ceiling and cheap light fixtures had to go. Mostly, she “just made it pretty. Calmed it down.”

Since moving here, she has accomplished a lot, steadily ridding the surrounding land of tangled overgrowth. In order to grow flowers (focusing upon pollinators, a passion) she tackled clearing the fields of seven years of tree growth.

Afterward, she used the sawdust from removing all those trees, recognizing it as a compatible medium for planting zinnia. But a storm made short work of her investment in seeds, fertilizer and lime — all laid to waste.

Undaunted, Benbow acquired her second, 50-acre farm using new auctioneering skills from Mendenhall School of Auctioneering. A slew of projects came with the parcel — outbuildings, a log cabin, even a country store. She keeps horses there in a fine new equestrian barn. A mare, she says proudly, recently foaled.

The dream, however, follows a personal tragedy. She and her late husband were birds of a feather. The doctor, medical professor and long-time member of the city council in Concord, was a Colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves Medical Corps. (He made headlines volunteering for multiple Middle East deployments when well past retirement age.)

Benbow reminisces about their meeting at Duke when she was a graduate student working in a lab and he was doing morning rounds as a pediatric urologist. (She nearly went on to medical school.)

Henry had surreptitiously “scoped her out” as she demonstrated to residents how to do cell cultures.

Initially, she was reserved, questioning how he obtained her number when he called her. He thought she might be an ice princess.

Before dating, she grilled Henry.

Had he ever done drugs? Was there another woman that would mind her having dinner with him? And, out of curiosity, what was his age?

“He answered no to the first two.” The age difference didn’t matter.

Three months later, they were engaged, marrying in 1992. She muses about the fact that only one of her four siblings didn’t pair up with a doctor.

Seemingly indefatigable, Henry died on Thanksgiving Day in 2014 at age 75 due to complications from a rare blood cancer. Her smile fades. For seven months following, she describes being “spiritually diminished.”

With Henry’s death, Benbow was forced to begin anew. She literally replanted herself.

Behind her Summerfield farmhouse, a colorful vista unfolds in summer. While she isn’t particularly good with flowers, Benbow shrugs. “I just try.”

Benbow has walked each furrow and hillock.

“Goldfinches, butterflies, all did well,” she muses, pleased that pollinators are appearing — even as she worries about their general decline. She is consumed by the need to support pollinators and began beekeeping, but lost her hives this past winter during severe cold. Still, there are emotional victories. It was a special moment watching deer wading into the sunflowers she had planted.

For someone who was first a scientist, she explains farming, too, is process dependent.

“You have to get into the process, and pray for the outcome. ‘I hope it works,’” she jokes, but is also serious.

Benbow recalls telling Rotarians just how humbling and uncertain it is.

“If you want to find religion, sit on a tractor thinking about those seeds you just spent $4,000 on,” she says, adjusting herself in her chair as if sitting atop a tractor: “You sit on that thing [hoping]. ‘It’s going to work. It’s going to work.’ And pull in all the good vibes of the universe.”

Last year, she lost both sunflowers and corn crops to drought. Losses are a piece of the human condition, as she is acutely aware. As for the romantic culture of growing what you eat and farm-to-table fantasies, she also understands how hard it is. Even basic crops like tomatoes, planted in the same place again and again, lead to soil depletion. Crop rotation is essential. She quickly outgrew the first farm — so acquired another.

With hands thrown up in a gesture of surrender, she laughs about how her best tomatoes are often volunteer plants randomly emerging from the seeds of tossed-out tomatoes. “With no memory of a potential pathogen there,” the science-minded farmer explains. The tenuous balance of earth and farming is a constant seesaw.

If enduring disappointment and difficulty prepare one for the unpredictability of farming, Benbow’s own childhood easily predicted the success of her marriage. Battling adult polio at age 25, her father endured 13 months in an iron lung when his wife was pregnant with their second child. Later, he adapted to walking with leg braces and refused to be a victim. He went on to create the first computing department at R.J. Reynolds.

He was never self-pitying, Benbow recalls.

Her mother, Jane, was a cartoonist in college yet skilled in math. Her father, William, was a poetry-writing engineer. A single thing didn’t define them.

She inherited both left- and right-brain talents from her polymath parents. And — a happy resilience that seems indomitable.

For a time after Henry’s death, Benbow was adrift, listening for an echo that was no longer there. Coping with not being part of a duet is painful.

“Much like in The Magic Flute,” she explains, “when the songs echo.” She confesses to “having leaks” when something triggers tears.

Alpha Awareness Training by Wally Minto led to recovering herself.

“It was basically saying, ‘What did you do as a child, and where was your joy?’ If you get back to the child in your past, you’ll find it.”

In surrendering herself to becoming lost, Benbow reliably found her way back.

Even as she kept her law practice and farmed, she explored further, attending auctioneering school and earning an associate’s degree in visual arts. “I’m a serial learner,” she playfully argues when accused of being a serial degree earner.

She insists she is a happy person, if a struggling farmer — and “even a happy lawyer.” But Benbow questions if Henry could have thrived here.

The problem was, Henry was a “bug magnet,” she jokes. Sensitive to mosquito bites, he was therefore never as keen on the country life. Plus, she would never have asked him to give up his multidimensional life.

A pensive Benbow looks outside towards the recently planted fields where flowers grew last year. Her mother often quoted a line attributed to Emerson. “The Earth laughs in flowers.”

“We had laughter in the house,” she adds wistfully.

“If you went into Mom’s house, it had a lot of energy,” she says. “Every surface was decorated with something she had made.” Each room of the farmhouse contains some of Benbow’s artwork. Her art is charged with color; exuberant, zestful.

Suddenly sheepish, she looks around her home, and adds, “This is turning into that!” After a beat, Benbow yelps.

“I’m turning into my mother!”

Behind her, the cloud cover breaks. Suddenly, sunlight drenches the fields, which seems to undulate, newly golden, where seedlings have barely emerged.

Benbow swivels, orienting her perspective to better see. Tender beginnings, which, if luck holds, will bring vigor, growth and maturity. If temperatures don’t swing madly, if there is rain and not drought, if pestilence stays at bay, there will be harvest and not heartbreak.

“Flowers are more beautiful,” she murmurs in a low register, her whole face softening into a hopeful smile.

Of course. She already sees the flowers.

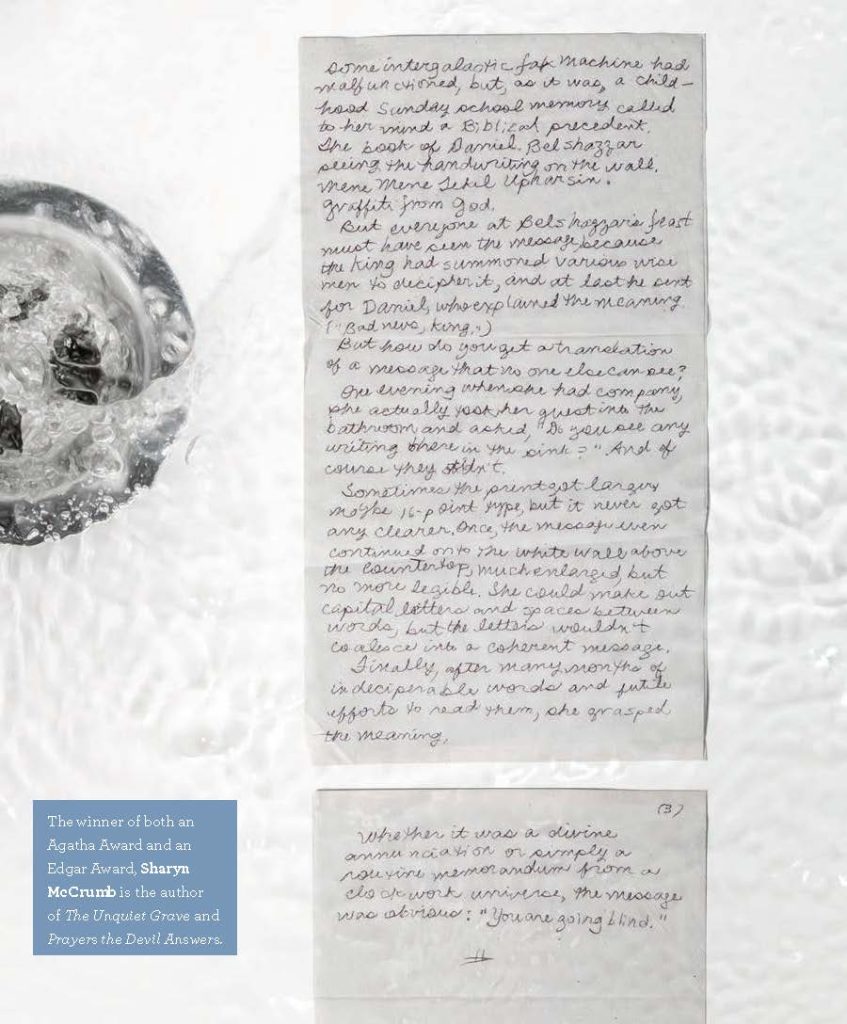

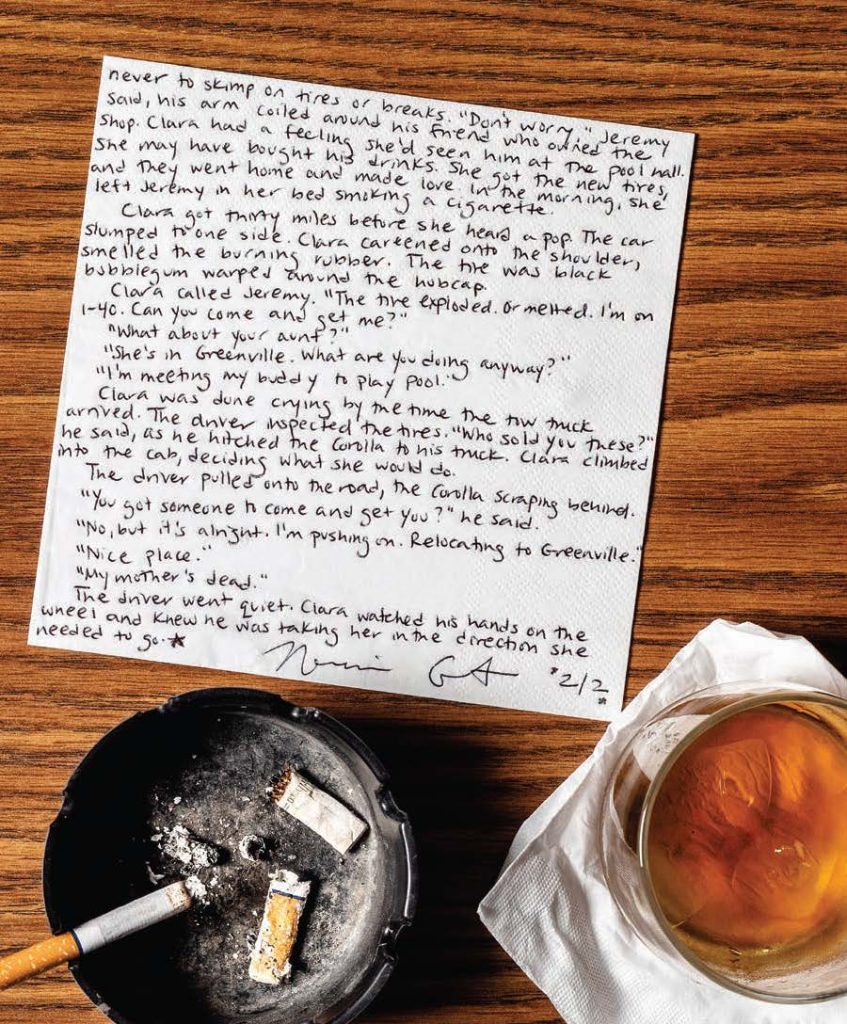

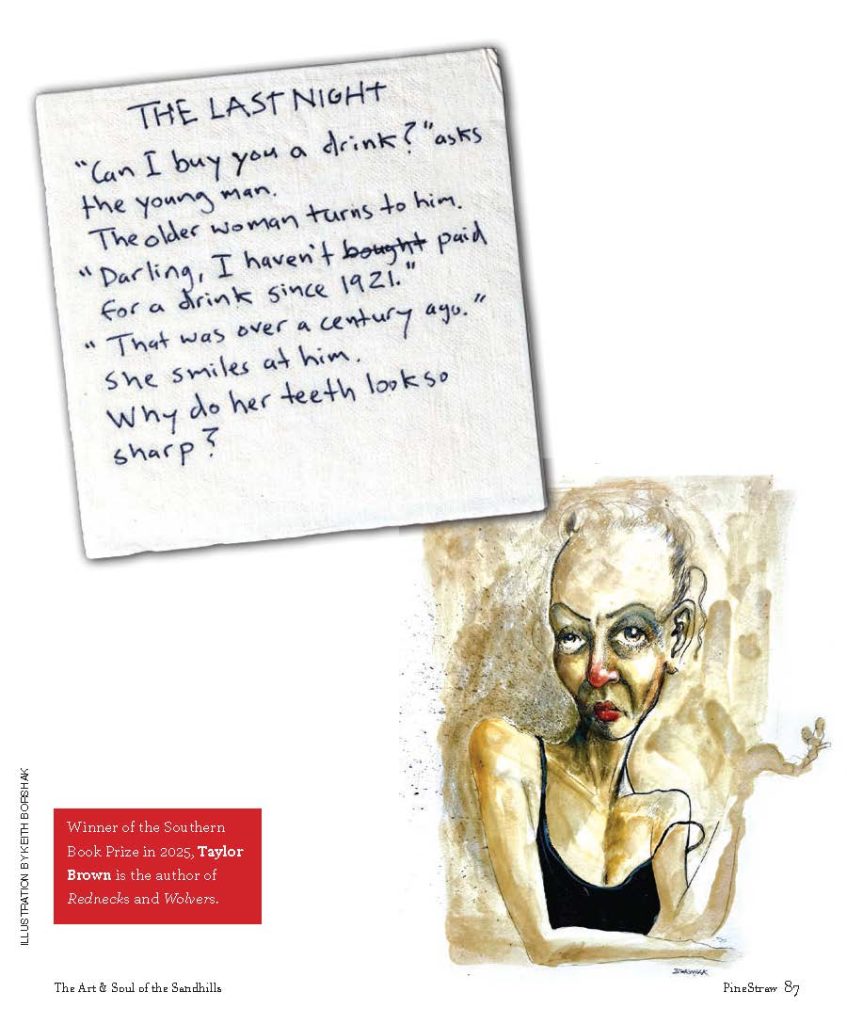

Paper Tales

Chaos Theory

CHAOS THEORY

The Game of the Name

An homage to Mark Twain, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Laura Ingalls Wilder

By Cassie Bustamante

When my daughter, Emmy, met her first-year Penn State roommate, Taylor, online this summer, the young women exchanged full names for their roommate request forms.

“Emerson is your full name?” Taylor texted. “It’s really pretty! My mom thought so, too.”

“Yeah,” Emmy replied. “My mom gave us all literary names. I’m named after Ralph Waldo Emerson. My older brother, Sawyer, is named after Tom Sawyer, and my little brother, Wilder, after Laura Ingalls Wilder.”

“That is actually so badass,” messaged Taylor. “I aspire to name my kids after literary legends like your mom.”

As for my own first name, it did not come from literature. Nor did it come from Greek mythology. You know the story — the ill-fated Cassandra, able to see the future with utter clarity but cursed by Apollo to be believed by no one. So many times, I had to explain that wasn’t even close to what my mother had in mind. She’d been just 13 when she heard it on the original vampire soap opera, Dark Shadows, swearing that if she one day had a daughter, she would name her Cassandra, just like the show’s witch. Nine years later, I was born.

“But she was just so beautiful,” my mom said, telling me, in her defense, about how my name had a dark side. Never mind that she was not a good witch by any stretch of the imagination.As a teenager myself, I’d landed on the name Hadley if I ever had a girl. Ah, Hemingway’s wife, right? Alas, that’s not my source. You see, I grew up in a small town in Western Massachusetts. We weren’t far from charming places you may have heard of, like Northampton and Amherst. Nestled between them is the quaint village of Hadley and below that, naturally, is South Hadley, home to my favorite woodsy escape during my high school years: Skinner Mountain. I took countless hikes there with my dad or with friends, sometimes both.

Nearby was a café called the Thirsty Mind, still there today. After a fall hike, we’d reward ourselves with giant chocolate chip cookies and steaming cups of hot cocoa. Or my pals and I would venture there at night, sipping tea and playing Chinese checkers or one of the many other well-loved games the shop had lying around. All that to say, South Hadley holds a special place in my New England-loving heart.

So, when my husband, Chris, and I found ourselves preparing for our first child in 2005, I was sure I was carrying little miss Hadley. That is, until the doctor pointed out that I may want to consider Hudson versus Hadley because there on the ultrasound were very clear boy parts. I spent the next couple of months agonizing over names. As an Enneagram type four (the personality-type system’s “individualist”), I wanted a name I’d never heard on another person before. The English major in me thought perhaps literature could inspire me and I recalled the collections of novels my brother and I had on our shelves as children. One stood out: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

“Sawyer,” I said aloud to Chris.

It was a good, strong name, he agreed. What he didn’t dare tell me was that there was a character named Sawyer on his current favorite television show, Lost, which began airing just a few months before I found out I was pregnant. By the time someone mentioned it to me, I was already calling the growing baby in my belly Sawyer. It was a done deal.

When Sawyer was 9 months old, we found out his little sister was on the way. And while I still loved the name Hadley, its time had passed.

“What about Emilia?” I asked Chris. “Emilia Bustamante. Doesn’t that sound pretty? And we could call her Emmy.”

“Sounds too Spanish,” he replied dryly.

“Um, you are Cuban,” I said.

“I do like Emmy, though,” he said.

With that in mind, I continued to ponder names. What else could I shorten to Emmy?

Emma? Too common.

Emmet? All I could picture was a washtub-bass-playing Muppet otter.

Emerson, as in Ralph Waldo Emerson, poet, writer, philosopher? Sign this literary-lover up!

Years later, when the last of our gaggle of children was due to arrive, I decided he had to follow the precedent we set with his siblings — a name inspired by a writer or literary character. I was not a Thornton Wilder fan, so apologies to those who think the baby of our family, Wilder, was named for him. But Laura Ingalls Wilder? Yes, indeed. I’ll take Little House over Our Town any day. So infatuated was I as a child that my mother sewed me a floral dress, apron and bonnet so that I could not only appreciate Laura, but I could channel her, too.

And now Wilder will have to go through life probably explaining to people, “No, no. My mom’s a big book nerd, but it’s not that playwright Thornton dude or even the kid from the novel White Noise. Nope — I’m named after some little girl who lived in some little house on some great big prairie.”

“But she was a brilliant writer,” I’ll tell him! And I’ll remind him of the quote of hers I had over his crib when he was a baby: “Some old-fashioned things like fresh air and sunshine are hard to beat. In our mad rush for progress and modern improvements let’s be sure we take along with us all the old-fashioned things worth while.” Like a good name.