O.Henry Leading Women July 2025

Lessons in Husbandry

LESSONS IN HUSBANDRY

July 2025

Lessons in Husbandry

In Pleasant Garden, Drew and Lacey Grimm are perpetual students and teachers

By Cassie Bustamante • Photographs by John Gessner

About a half-mile from Hagan-Stone Park sits “The Schoolhouse,” a rustic, tiny home with a vibrant barn quilt hanging above its front door. A vintage roadside marquee sign that has been lettered with “Happy” greets passing cars, its arrow pointing directly to the house. Upon entering, it’s easy to imagine something straight out of Little House on the Prairie — a blackboard at the back and benches where children would sit, lunch pails tucked under the seats. “If you don’t tell people it wasn’t a schoolhouse, they’d think it was,” says Lacey Grimm, who owns the property with her husband Drew.

Keep following the gravel drive past The Schoolhouse and you’ll reach the family homestead, where Drew and Lacey are raising and homeschooling their four children: Naomi, 20; Leviah, 16; Eliza, 14; and Abraham, 9. Drew and Lacey have been the kids’ educators from the start. In fact, when they first moved to Greensboro two decades ago, they began their first farmstead — a small, “urban farm” near Four Seasons Mall, where they had bees, chickens and a yard overtaken by garden. They called that little project “Schoolhouse Farm” because they were homeschooling, but also because Lacey had a blog called “Life Is a Schoolhouse,” where she imparted the lessons they’d learned through homesteading.

In 2012, seeking more land and farming opportunity, the family moved into their Pleasant Garden “foreclosure in the woods,” as Lacey calls it. Plus, she says, their family is Jewish and “a lot of the Jewish tradition is agricultural,” and much of their faith’s ancient approach to husbandry is rooted in sustainability. “You can’t do it if you don’t have a farm,” she notes. So, taking the Schoolhouse Farm name with them to the new place — a 10-acre plot with a ranch that needed a total overhaul — they dug in.

“It’s not what the dream was — the old farmhouse — but now that we have this,” says Lacey, waving her hand around The Schoolhouse, “it sort of scratches that itch.”

But don’t let the name fool you. What the Grimms have hatched is much more than a schoolhouse. And you won’t find reading, writing and arithmetic within these walls. Instead, you’ll find a place that this pair of homegrown, serial entrepreneurs cultivated with care, a hive of free enterprise built around their own fascination in modern homesteading and farming. The Schoolhouse, appropriately, has grown into a community space, where like-minded people congregate to learn about how the Grimm family is embodying the latest in the back-to-the-Earth movement.

“I feel like we’ve got a dream life compared to most people,” says Drew. “A lot of days, we don’t have to leave the homestead. We have everything.”

But this little one-room building on the ’stead wasn’t theirs for the itch-scratching until 2018. When they moved into their house, the 900-square-foot home and its surrounding 5 acres wasn’t on the market and was being rented. As luck would have it, a “For Sale” sign eventually went up. The Grimms imagined what they could do with that added acreage.

“Where are we going to come up with $100,000!” Lacey recalls wondering, their primary income coming from her sales of dōTERRA essential oils and related products. But within two days, the owner came down significantly on the price and, Lacey quips, “It turns out people will give you loans really easily on the internet.” Before they knew it, $50,000 cash was in their hands, enough to make the purchase. And, Drew notes, he’d just sold a business, so they’d be able to pay back the loan almost immediately without worrying about exorbitant interest rates.

As soon as their names were on the deed, the Grimms pushed up their sleeves and got to work. The home had seen better days. “I can’t believe anyone was living here,” says Lacey.

“We took it down to the dirt floors and rebuilt it,” says Drew, a baseball cap resting atop his long, gray-and-brown hair, his full beard a mix of the same. He sits in a wooden cricket chair that echoes the 1940s era of The Schoolhouse.

In the process of gutting the home, they learned a little about its history and ties to the land. Their next-door neighbor, an elderly gentleman well into his 80s now, regaled the couple with tales of the home’s construction. The lumber, he told them, was all sourced from trees on the property itself, and he and his father sawed, hammered and built it from the ground up. Of course, he also claims that when he was a small child, he was lowered down to dig the nearby well. “Like any good country man, I am not sure how much of it is tall tale,” Drew says, chuckling. “But it is kind of cool to have that connection to the house and to the land — and to the old guy!”

Knowing the building’s past, they set their eyes on the future, picturing a place where they could bring people together. “If we are going to have a community space, it’s got to be ‘The Schoolhouse,’” Drew recalls saying.

For Lacey, that meant getting down to the nitty-gritty details. She insisted Drew move the front door over, only about 3 feet, so it would be centered on the facade. The kitchen was rearranged so that the sink sat underneath a window, where sunlight streams in. The ceilings were torn down, exposing the original wood and beams, but a loft was added to create sleeping space.

As for the decor? “She is a thrift master,” Drew says proudly of his wife. Nearby, Lacey, her sandy brown waves cascading past her shoulders, sinks onto a mustard-yellow, vintage velvet sofa. As it turns out, she helped her mom stock a vintage store before her kids were born and has an eye for pieces with history. The kitchen island? It came out of an N.C. State lab. The retro brown refrigerator, “Oh, it was just in our garage,” says Lacey.

Although Lacey claims she was just “hodgepodging together” The Schoolhouse furnishings, the overall look is cohesive and homey. Guests often tell her they feel as if they’ve been here before. “It’s a familiar feeling,” she says.

“I get a little choked up because it’s like, you know, you have a vision and it slowly, over time, becomes more than you could have expected it to,” says Lacey wistfully. “And now we have a schoolhouse.”

What was once barely livable is now a place of gathering, community and education. Lacey points to a painting on the wall. She decoarated the canvas in a recent workshop she cohosted here with artist Rebecca Dudley, who owns Triad Mobile Art Academy. The participants painted flowering medicinal herbs while also learning about them from Lacey and noshing on local wines and cheeses. The Grimms have also hosted a tasting with a local chocolatier as well as a four-course, farm-to-table Valentine’s dining experience led by their friend and chef Steve Hollingsworth.

“For the food club group, we had a trout dinner,” adds Drew, where Ty Walker, owner of Smoke in Chimneys, a sustainable fish hatchery in Southwest Virginia, cooked trout three ways.

Food club? Lacey explains that The Schoolhouse food club, which they call ComFoo for “community food,” is “sort of like a Costco situation.” Members order goods curated by the Grimms from farmers, keeping it as local as possible, including tough-to-find-so-close goods such as Cape Hatteras salt and rice from Wilmington.

Once every other week, food club orders are ready for pickup and The Schoolhouse bustles with life. Their members, Lacey says, have all gotten to know each other. They come for the food, but stay for the conversation and connection. And, each time, the Grimms welcome one or two producers to offer samples and education about their goods.

“We’ve always been passionate about the teaching aspect,” says Drew. Drew, Lacey notes proudly, recently became certified by the Savory Institute as a regenerative agriculture educator. With this under his belt, he’s able to help others make their own pastures more productive while remaining sustainable.

Plus, Lacey notes with a laugh, others can learn by “skipping some expensive mistakes” they’ve made. Mistakes such as goats.

On their original 10 acres, excited to try their hand at livestock, the Grimms brought in goats. Do they still have those goats. “No!” They answer emphatically and in unison. Goats, the Houdini of livestock, often hop fences and escape. Or, notes Lacey, their goats would get stuck in the fence multiple times in one day and they’d spend their time untangling horns and hooves.

They said goodbye to goats and brought in sheep next. “And we didn’t even have a dog, so we were just human herding these sheep,” Lacey says. That, too, got to be too much for them. Step one, she notes, is getting a sheepdog, which they’ve since done. “Maybe we will get more sheep eventually,” she muses.

The Grimms finally landed on cows and own two breeds: Dexter, a small variety, which Lacey feels is safer around kids; and Swiss Linebacker, a heritage dairy breed. Comparing the bovine’s disposition to their previous livestock, Lacey says, “Their vibe is just much slower and more easygoing.” Currently, the couple has five cows “and two on the way, any day now!”

With cows being the endgame livestock for them, Drew is currently in training to become a shochet, a Jewish butcher who has been specially trained and licensed to slaughter animals and birds in accordance with the laws of shechita and can certify kosher meats. His hope? “To be able to provide the Jewish community with sustainable, high-quality food.”

Still, educating others in their ways of life remains their focus. A nursery, says Lacey, “feels like a good idea to me.” Would she sell her plants? Absolutely, but they’d come with a side of education.

“She wants to talk,” adds Drew, grinning widely. “She’s a plant lady.”

“I can’t just sell you a plant,” says Lacey. “Come here and I will tell you all about this plant.”

Her light blue eyes glint as a memory crosses her mind. “Have you ever been to John C. Campbell Folk School?” she wonders aloud. “I went for basket weaving and I just fawn over the catalog every time it comes,” Lacey says. “So I would just love to have a space where that is happening all the time — like classes and workshops.”

As for if and when that will come to fruition? Lacey says that with young ones still at home, she’s in no hurry. “There is space for that down the road,” she says. And she could mean that quite literally.

Tea Leaf Astrologer

TEA LEAF ASTROLOGER

July 2025

Cancer

(June 21 - July 22)

It’s your party and you’ll cry if you want to. We know, we know. We’ve all heard the song. That said, with Venus in Taurus until July 22, get ready for more emotional stability than you know what to do with. On the other hand, with Mercury going retrograde on July 17, a hiccup in communication could lead to a bit of a misadventure. The good news: Your intuition will guide you from here. The better news: There’s no going back.

Tea leaf “fortunes” for the rest of you:

Leo (July 23 – August 22)

Replace the filter.

Virgo (August 23 – September 22)

Dare you to dance in the rain.

Libra (September 23 – October 22)

Butter the toast.

Scorpio (October 23 – November 21)

Stop and smell the sweet pea.

Sagittarius (November 22 – December 21)

Hint: Take five.

Capricorn (December 22 – January 19)

The “Hot Light” is on.

Aquarius (January 20 – February 18)

Start labeling the leftovers.

Pisces (February 19 – March 20)

Bring a book along.

Aries (March 21 – April 19)

Three words: Lose the ’tude.

Taurus (April 20 – May 20)

Put your phone down.

Gemini (May 21 – June 20)

Let your actions speak for themselves.

Chaos Theory

CHAOS THEORY

July 2025

Frozen in Time

A good-to-the-last-melted-drop tour of area ice cream shops

By Cassie Bustamante

If you could only eat one thing for the rest of your life, what would it be? It’s one of those questions that pops up as an ice breaker in awkward social settings. My answer is always at the ready: ice cream! And in a recent and not-quite-scientific study, 80% of participants (four out of five people in my nuclear family) agreed, sharing my unmelting devotion. Sawyer, my 19-year-old outlier, would take a baked good over a chilled sweet treat any day (and every day). But my youngest, Wilder? Well, the scoop doesn’t fall far from the cone.

At the very beginning of last summer as I looked ahead to hectic weeks of juggling Wilder’s camp schedule with my own work schedule, I felt overwhelmed — and a tad bit guilty that he’d be shuffling from camp to camp. I decided to give us something to look forward to every Friday afternoon, ending the week on a sweet note.

“What if we spend the summer taking an ice cream tour of Greensboro?” I ask 6-year-old Wilder one June afternoon. “Every Friday, we could chill at a new spot in town?”

“Yes!” he emphatically answers. “I love ice cream!” Not that I thought I’d have to twist his arm.

While I am a Leo who lives in typical creative chaos, my rising sign is a Virgo — meaning, I love a good spreadsheet. I get to work right away making a Google Sheet listing all of the local ice cream shops I can think of; plus, I hit up friends for recommendations and, of course, ask the all-knowing internet.

We begin our journey with a brand-new shop we’ve never been to on Battleground called Ice Cream Factory. Wilder orders a scoop of superman — a swirl of bright red, yellow and blue. If I told him it was entirely fruit flavored, including strawberry and banana, he’d never eat it. But, marketed as a comic book hero, he’s all in. Meanwhile, I pair key lime with raspberry roadrunner — a heavenly combination that tingles my palate. A shelf in the back is piled high with all sorts of games and puzzles. Long after our spoons have scraped the last of our treats from our cups, we spend an hour-and-a-half playing Trouble, Connect Four and cards.

In the car on the ride home, I ask, “What did you think of that place?”

It’s not technically a factory, he informs me in a tone of total authority, “but I guess they liked the name Ice Cream Factory. If it was a factory they would have machines that made the ice cream there and they would have robot arms that gave you the ice cream.” I stifle a giggle.

“OK, so, on a scale of one to five stars, how many stars would you give it?”

He pauses in serious contemplation. “Five stars.” Turns out, there’s no point deduction for the lack of robots.

At Yum Yum, a Greensboro staple since 1906, Wilder orders birthday-cake-flavored ice cream. After he’s finished every last melted drop, he announces, “I like superman better.” We’d committed to trying new-to-us flavors at each spot and it isn’t lost on Wilder that Yum Yum has its own superman flavor on the menu, which, clearly, he wishes he’d been able to order. Yum Yum, in Wilder’s highly calculated opinion also earns a five-star rating “because the place is pretty cool and it has a good name.”

At Maple View in Gibsonville, lured by its vibrant rainbow colors, Wilder orders a sherbet. It’s too sour for his tongue, he tells me. Funny, that doesn’t stop him from eating it all and awarding the shop five stars. Why? “It’s a really great place,” he says, “but not good ice cream.” I think he was also a big fan of the huge chocolate ice cream cone in the window.

Our summer Fridays continue on like this, visiting Ozzie’s, Homeland Creamery and everywhere in between, Wilder doling out five stars to almost every institution. Well, except for Cook-Out, where he ordered a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup shake and discovered he didn’t like big chunks of anything — even milk chocolate and sugar-laden peanut butter — interfering with the uninterrupted delivery of ice cream through the straw into his mouth. “Three stars,” he pronounces gravely. I explain that Cook-Out shakes are meant to be eaten with a spoon sometimes, but he’s not having it. Meanwhile, my 18-year-old, Emmy, and I gleefully gorge ourselves on our mint Oreo shakes, while my husband, Chris, gulps down his Butterfinger.

Turns out, if you do your research, there are enough five-star ice cream shops in the area to fill an entire summer’s worth of Fridays — and then some.

While we aren’t repeating the tour this summer, two new shops have since opened, plus we’re always up to sprinkling in repeat stops. And the cherry on top is that, this time, I don’t give a lick what he orders and how many stars he doles out. Because, as it turns out, it’s not about the ice cream at all. It never was. It’s about freezing a moment in time between a mom and her son.

The Great Wagon Road Odyssey

THE GREAT WAGON ROAD ODYSSEY

July 2025

THE GREAT WAGON ROAD ODYSSEY

A pilgrimage half a century in the making

By Jim Dodson

Not long ago, during a breakfast talk in a retirement community about my forthcoming book on the Great Wagon Road, I was asked by a woman, “So, looking back, what would you say was the most surprising thing about your journey?”

“Everything,” I answered.

The audience laughed.

The first surprise, I explained, was that it took me more than half a century to find and follow America’s most fabled lost Colonial road that reportedly brought more than 100,000 European settlers to the Southern wilderness during the 18th century. As I point out in the book’s prologue, I first heard about the GWR from my father during a road trip with my older brother in December 1966 to shoot mistletoe out of the ancient white oaks that grew around his great-grandfather’s long-abandoned homeplace off Buckhorn Road, near the Colonial-era town of Hillsborough.

The first of many surprises was the discovery that my father’s grandmother, a natural healer along Buckhorn Road named Emma Tate Dodson, was possibly an American Indian who had been rescued and adopted as an infant by George Washington Tate, my double-great-grandfather, on one of his “Gospel” rides to establish a Methodist church in the western counties of the state.

A second surprise came during the drive home when the old man pulled over by the Haw River to show my brother and me a set of stones submerged in the shallows of the river — purportedly the remains of G.W. Tate’s historic gristmill and furniture shop.

“Boys, long ago, that was your great-great-granddaddy’s gristmill, an important stop on the Great Trading Path that connected to the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road that brought tens of thousands of European settlers to the South in the 18th century, including your Scottish, German and English ancestors.”

This was pure catnip to my lively eighth-grade mind. Owing to a father whose passion for the outdoors was only matched by his love of American history, my brother and I were seasoned explorers of historic Revolutionary and Civil War battlefields.

“Can we go find it?” I said to him.

He smiled. “How about this, Sport. Someday I’ll give you the keys to the Roadmaster, and you can go find the Wagon Road.”

I searched for years but found only the brief occasional mention of the Great Wagon Road in several histories of the South, but nothing about where it ran and what happened along it. The road seemed truly lost to time.

Forty years later, however, the Great Wagon Road found me.

On my first day as writer-in-residence at Hollins University in Virginia in 2006, I took a spin up historic U.S. Highway 11 — the famed Lee-Jackson Highway — and was surprised to come upon a historic roadside marker describing the “Old Carolina Road” that was part of the 18th century’s “Great Philadelphia Wagon Road.”

The sweet hand of providence was clearly at work, for the next day, while browsing shelves at a used bookshop in the Roanoke City Market, I found a well-worn copy of a folksy history called The Great Wagon Road: From Philadelphia to the South, by Williamsburg historian Parke Rouse Jr. I purchased the book (originally published in 1973 and long out of print) and read it in one night, taking notes. I also attempted to track down author Parke Rouse Jr. but discovered he’d been deceased for many years.

Still, the cosmos had cracked open a door, and I began collecting and reading all or parts of every history of America’s Colonial era that I could lay hands on for the next decade, eventually building a personal library of more than 75 books. About that same time, I purchased a 1994 Buick Roadmaster Estate station wagon from an elderly man in Pinehurst, almost identical to the one owned by my late father in the mid-1960s. Pinehurst pals playfully nicknamed it “The Pearl,” which turned out to be among the last true “wagons” built by Detroit before they switched to making SUVs.

I suddenly had my very own wagon. Now all I had to do was find the most traveled road of Colonial America to travel in it.

Eight years later, thanks to the late North Carolina historian Charles Rodenbough and other history-minded folks, I discovered that I wasn’t alone in my quest — that, in fact, a small army of state archivists and local historians, genealogists, “lost road” experts, various museum curators and ordinary history nuts like me had finally cracked the code on the road’s original path from Philly to Georgia.

By the spring of 2017, I and my traveling pal, Mulligan the dog, were ready to roll when another big surprise — an exploding gallbladder and a baby carrot-sized tumor in my gut — required surgery and a four-month recovery.

Finally, on a steamy late August night, I began my journey (minus Mully, alas, owing to her age and one of the hottest summers on record) at Philadelphia’s historic City Tavern, which claims to be the birthplace of American cuisine. As I enjoyed a pint of Ben Franklin’s own spruce beer recipe and nibbled on cinnamon and pecan biscuits from Thomas Jefferson’s own Monticello cookbook, I eavesdropped like a tavern spy from Robert Louis Stevenson on three couples having a rowdy celebration of matrimony and a game of trivia based on American history that kept going off the rails.

At one point, a young woman called out a question in clear frustration: “Where and what year were the Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first constitution, adopted?”

None of her mates answered.

So, I did. “I believe it was York, Pennsylvania, in November 1777.”

Her name was Gina. She gave me a beaming smile and scooted her chair close to mine. “Correct! How did you know that?”

“Because it happened on the Great Wagon Road.”

What ensued was a delightful conversation about a frontier road that shaped the character and commerce of early America, the historic Colonial road that opened the Southern wilderness and became the nation’s first immigrant highway — the “road that made America,” as my friend Tom Sears, an Old Salem expert on Colonial architecture, described it to me.

Gina was thrilled to learn about it and apologized that she’d never heard its name.

I assured her that she wasn’t alone. Most Americans living today have never heard its name spoken, yet it’s believed that one-fourth of all Americans can trace their ancestral roots to the Great Wagon Road in one way or another.

Charmed and fascinated, Gina wondered how long it would take me to travel the road from Philly to Augusta, Georgia.

I mentioned that settlers took anywhere from two months to several years to reach their destinations depending on the weather and unknown factors like disease, getting lost or encountering hostile native peoples or wild animals.

“I plan to travel the entire road in three or four weeks,” I said. “I’ve spent years researching it.”

Silly me. God laughs, to paraphrase the ancient proverb, when men make plans.

A third big surprise came at the end of my third week on the road. I hadn’t even gotten out of Pennsylvania.

On the plus side, I’d met and interviewed so many fascinating people who were passionate keepers of their own Wagon Road stories, I realized I’d just tapped the surface of the trail’s saga.

Instead of writing an updated history of the Great Wagon Road, as originally planned, I borrowed a strategy from my late hero Studs Terkel and decided that the real story of the Wagon Road lay in the voices of the people living along it today, keeping its stories alive — the flamekeepers, if you will, of the “road that made America.” If it took a full year to complete my travels, so be it.

Instead, subtracting 12 months for COVID, it took six years and counting.

My focus on the storytellers proved to be deeply rewarding, introducing me to a broad array of Americans from every walk of life and political persuasion whose vivid and often untold tales about the development of a winding and once forgotten Colonial road (originally an American Indian hunting path that stretched from Pennsylvania to the Carolinas) carried our ancestors into the Golden West and shaped the America we know today, hence the book’s main title: The Road That Made America. Unexpectedly, their voices and stories ultimately restored my faith in a country where democracy — and civic discourse — was supposedly in short supply.

Looking back, this was the nicest surprise of all. For what began simply as an armchair historian’s quest to find and document America’s most famous lost road ended as nothing less than a powerful, emotional pilgrimage for me.

At the journey’s end, while I was heading home through the winter moonlight on a winding highway believed to be the path Lord Cornwallis took while chasing wily Nathanael Greene to the Dan River, I had a final revelation of the road’s impact on me:

. . . a true pilgrimage is said to be one in which the traveler ultimately learns more about himself than the passing landscape.

Perhaps this is true. But for the time being, it’s enough to think about some of the inspiring people and stories that gave me hope in a nation where democracy is said to be hanging by a thread: an old Ben Franklin and a young Daniel Boone, the Susquehanna Muse, real Yorkers, the candlelight of Antietam, a Gettysburg living legend, an awakening at Belle Grove Plantation, Liberty Man, the passion of Adeela Al-Khalili, good old cousin Steve, a lost Confederate found, a snowy birthday in Staunton, and final road trips with Mully.

Without question, my life and appreciation of my country have both been enriched by the people and stories of the Great Wagon Road.

This was the nicest surprise of all.

Almanac July 2025

ALMANAC

July 2025

Almanac July 2025

By Ashley Walshe

July is a backyard safari, dirt-caked knees, the heart-racing thrill of the hunt.

Bug box? Check. Dip net? Check. Stealth and determination? Check and check.

Among a riot of milkweed, blazing star and feathery thistle, the siblings are crouched in the meadow, waiting for movement.

“There,” points one of the children.

“Where?” chimes the other.

“Follow me!”

As they slink through the rustling grass, playful as lion cubs, life bursts in all directions. Monarchs and swallowtails stir from their summer reverie. Dog-day cicadas go silent. A geyser of goldfinches blast into the great blue yonder.

“He’s right there!” the child whispers once again, inching toward a swaying blade of grass.

At once, the black-winged grasshopper catapults itself across the meadow, popping and snapping in a boisterous arc of flight. The children scurry after.

On and on this goes. Hour by hour. Day by day. Grasshopper by grasshopper.

Or, on too-hot days, tadpole by tadpole.

“Race you to the creek!” chime the siblings.

Shoes are cast off with reckless abandon. Bare feet squish into the cool, wet earth. Laughter crescendos.

The whir of tiny wings evokes an audible gasp.

“Hummingbird!” says the younger one, scanning the creekbank until a flash of emerald green catches their eye.

As hummingbird drinks from cardinal flower after vibrant red cardinal flower, the children, too, imbibe summer’s timeless magic.

Finally, awakened from their fluttering trance, the children bolt upright.

“Race you to the wild blackberries!” they dare one another.

Such is the thrill of wild, ageless summer.

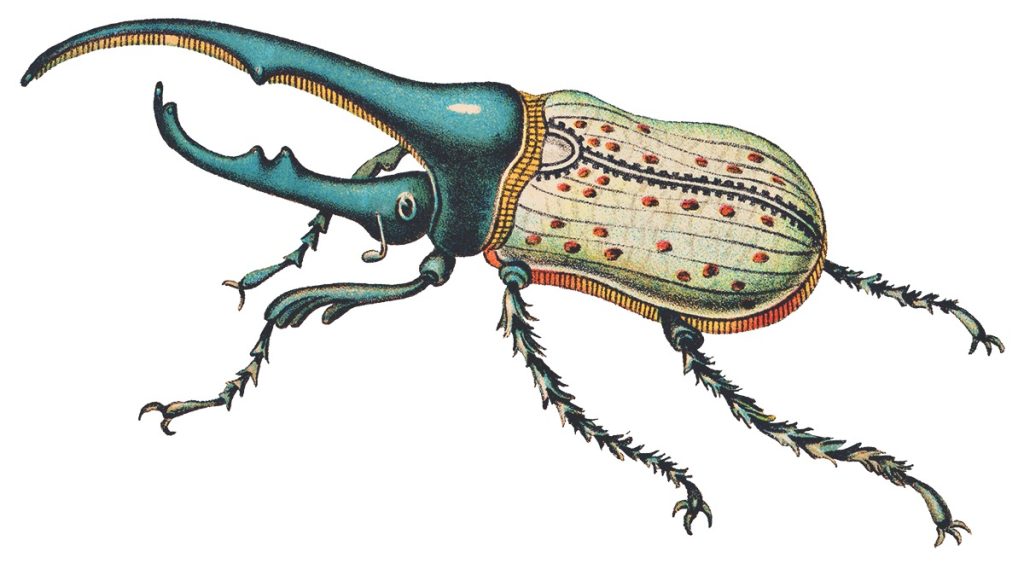

Mythical Creature Alert

What in all of Gotham City was that? Eastern Hercules beetles are in flight this month. Should you spot one of these massive rhinoceros beetles — native wonders — keep in mind that their larvae grub on rotting wood, breaking down organic matter to enhance our soil and ecosystems. As their name suggests, they’re sort of like superheroes without the lion skin or triple-weave Kevlar suit.

Life's a Peach

As burlesque icon Dita Von Teese once said, “You can be a delicious, ripe peach and there will still be people in the world that hate peaches.”

Oh, really? Who?

Peach season is in full swing. Dare you to drive past a local farm stand without braking for a quarter-peck or more. Kidding, of course. One should always make the pit stop.

True homegrown peach enthusiasts know that the annual N.C. Peach Festival takes place in Candor — Peach Capital of N.C. — on the third weekend of July. Get the sweet (and savory) details at ncpeachfestival.com.=

Life’s Funny

LIFE'S FUNNY

July 2025

Here’s the Scoop

Dogs and humans find their joy, one lick at a time.

By Maria Johnson

It’s a homecoming for Cash.

Last year, the spotted pup — he’s probably a mixture of Catahoula leopard dog and pit bull — was adopted from the SPCA of the Triad and taken home to Sanford to live with his new owner, Alicia Ferreira, and her parents.

In a nod to his origin, 16-month-old Cash and his family have returned to Greensboro, appropriately enough on Mother’s Day, to support an SPCA adoption event at State Street’s Bull City Ciderworks.

The scene includes a truck that serves frozen confections made specifically for dogs. Alicia steps up to the window and orders a scoop for Cash, who waits patiently, even though he appears to be hungry. He sniffs then picks up a piece of gravel in the parking lot. Someone fishes it out of his mouth.

“He loves a rock,” Alicia says with a sigh.

A minute later, she offers him something more enticing: a taste of maple-bacon-flavored ice cream. With eyes riveted on the cardboard cup, Cash waits for Alicia to spoon feed him. He licks with gusto. And manners.

“He’s very respectful when it comes to treats,” Alicia says.

She offers him the garnish, a twig of a chicken crisp, and it disappears in one chomp.

“He’s very into it,” says Alicia, who’s wearing laser-cut dog earrings.

She’s smiling.

Her dad is smiling.

Her mom is smiling.

And the truck’s owner, Shelli Craig, is smiling. This is the response that she and her family have been getting ever since last summer, when they rolled out North Carolina’s only franchise of Salty Paws, a Delaware-based business founded on the notion that there are plenty of dog owners who want their charges to know the joys of lapping ice cream until they get brain freeze.

Yip-yip-yip. A little waggish humor, there. No one has reported seeing a pup pause mid-lick, shudder, howl and bury its head in its paws until the throb passes. Although, just for the record, Google AI says it’s possible for dogs to get ice cream headaches.

The point is, when Shelli, a professional photographer and longtime dog lover (“Puppy breath is my drug of choice”) heard about Salty Paws from her friend, Kathie Lukens, the owner of Doggos Dog Park & Pub in Greensboro, she thought a franchise would be the perfect business for her family.

With eight children in her family — some biological, some adopted, several with disabilities — perhaps it seems like a wild notion. But then, when her youngest, who lives with cerebral palsy and migraine headaches, graduated from high school, she had a question: “What am I going to do for a job?”

Shelli’s answer: We’ll create jobs by starting a business that everyone in the family enjoys. Her husband, Daniel, part-owner of another family enterprise, R.H. Barringer Distributing Co., a wholesale beer business, enthusiastically endorsed the plan.

Shelli was unleashed. She bought a slightly used cargo van in Florida and had it transported to Virginia, where it was wrapped in franchise decals featuring a puppy with an ice cream-dappled nose, licking a frosty scoop of Salty Paws’ finest.

She ordered the powders used to make the canine ice cream — basically dried lactose-free milk with a little sugar and some flavorings.

She and the kids mixed the powders with water, poured them into cartons and froze them at home. Because the product is not intended for human consumption, no health department inspections were required. The process was pretty easy.

On fair-weather weekends, the family rolled out in the van, which is technically considered a feed truck, not a food truck.

Usually, Daniel drove.

To dog parks.

And pet adoption fairs.

And fundraisers for animal rescues.

And to dog-friendly events, like some outdoor car shows. Rovers mingling with Land Rovers? Who knew?

Dog-friendly bars such as Doggos were a staple.

The brightly painted truck drew a lot of attention with its drool-inducing flavors, including pumpkin, vanilla, peanut butter, maple bacon, straight-up bacon, birthday cake, carob and prime rib, which appealed to all sorts of meat lovers.

Once, a man came to the window and explained that he wanted to try a scoop of prime rib in the same way one might want to try a Harry Potter earthworm-flavored jelly bean.

Shelli explained that Salty Paws products were not intended for humans, but also, if he bought a scoop and a spoon, she could not control what happened next.

The human verdict after licking? OK.

Another time, a woman and her two children came to the window and bought a scoop of vanilla and a scoop of peanut butter.

As they walked away, Shelli wondered if the woman had mistakenly bought the ice cream for her girls.

A few minutes later, a man came to the window asking if they sold smoothies, too. Shelli explained that they sold ice cream for dogs.

“Dogs?! Oh, crap,” the man said before muttering about whether his kids would start barking soon.

Shelli and Daniel, who was known for his dad jokes, shared more than a few laughs over the stories that spun out of Salty Paws. Underlying their bond, Shelli says, was a shared commitment to beings in need.

“He had a very, very tender heart,” Shelli says of Daniel.

Tears well in her clear, blue eyes.

In April, Daniel died unexpectedly, of a heart attack, at age 59.

Shelli parked the Salty Paws truck for about a month as she grappled with Daniel’s absence.

“We built a big life with a lot of moving parts,” she says. One of the moving parts was Salty Paws.

It took a lot of resolve for Shelli to set aside her grief, load the truck on Mother’s Day, of all days, today, drive it to the cidery with two of her sons and start scooping ice cream.

“I’ve had to compartmentalize somewhat. Children and animals can bring me out of it,” she says. No surprise coming from a woman who wears a T-shirt emblazoned with “Tell Your Dog I Said Hi.”

She looks around. An SPCA volunteer walks by, cradling a weeks-old puppy. Nearby, an older, adoptable dog gnaws happily on a bully stick, a freebie from Shelli and family.

Cash savors his maple-bacon treat, totally absorbed.

His owner, Alicia, captions the moment aloud: “Best. Day. Ever.”

Quick as a lick, Shelli laughs, suspended for a moment in another place.

O.Henry Ending

O.HENRY ENDING

July 2025

Obits and Pieces

The tale of a quirky hobby practically writes itself

By Cynthia Adams

Collecting clever obituaries is a hobby of mine.

It’s a far less time-consuming undertaking, erm, endeavor, than you might think.

Interesting obits are as rare as zorses (a zebra and horse hybrid). When they happen, the social media universe is alerted and the obit boomerangs around 10 jillion times. Fun, intriguing, even weird obituaries are snapshots of the strangest of hybrids: the rare, true originals who have roamed this Earth.

Douglas Legler, who died in 2015, planned his obit for the local newspaper in Fargo, N.D. “Doug died,” he wrote. Just two words guaranteed a smile and a wish that we had known him.

Yet navigating the truth about our dearly departed is a tricky thing. I know, having attempted writing tender, true or even mildly interesting obits.

Uncle Elmer’s beer can collection or lifelong passion for farm equipment may not a fascinating individual reveal, but it beats ignoring the details that made Elmer, well, Elmer. Maybe loved ones wish to eulogize a different sort than they actually knew, say, an Elmer possessing panache. Ergo, an unrecognizable Elmer.

My father, in fact, worried that his own obit might one day portray him as suddenly God-fearing, upright and flawless.

“I know some will probably show up for my funeral just to be sure I’m dead,” he’d joke, shucking off the funeral suit we nicknamed his dollar bill suit — the tired hue of well-worn money. It didn’t even complement his twinkling green eyes, which seemed especially twinkly after a funeral or wake.

Why so upbeat? “It wasn’t me,” he sheepishly confessed after the funeral of a prickly neighbor.

Bob, an older, popular colleague of mine, had a sardonic wit, too, even as personal losses mounted. Each Friday he’d drawl, “Guess me and Becky will ride down to Forbis & Dick tonight and see who died. Then we might go to Libby Hill for dinner.”

In a similarly irreverent spirit, I offered to help my father with his funeral plans in advance, jabbing at his habitual lateness. “You’ll be late for your own funeral,” I accused.

“We’ll request the hearse to circle town before the service so we’re all forced to wait the usual half hour.”

Dad rolled his eyes.

He died suddenly at age 61. Much later, I wished we had mentioned in his obituary how his end was almost as he’d hoped: in the arms of a beautiful woman.

True, his newest paramour had arms. They may, in fact, have been her best attribute. (My siblings never let me near his obituary.)

To our surprise, Preacher Lanier wanted to speak at Dad’s funeral. But Dad was not a churchgoer, we said delicately; the service would be at the funeral home. Then he revealed that they were old friends, breakfasting together each Wednesday.

Carefully, I asked that he not proselytize — as he was often inclined. He knew our father far too well to do that, he chuckled.

True to his word and a shock to me, the preacher revealed that our father underwrote the church’s new well.

Disappointingly, there would be no tour of town before the service either; the hearse wasn’t involved until we drove to the interment.

For once, therefore, Dad was exactly on time.

Like funerals, obits offer the chance to surprise us in a good way.

Lately, my friend Bill got me thinking about mine. Given my inglorious beginnings in Hell’s Half Acre, he knew exactly what he’d say at my end.

“I’d say I’d have you buried in a trailer, but it would cost too much to dig the hole,” he quipped, mocking my uncultured life.

I would never admit it to him, but that was pure genius; it ought to at least be mentioned in my obit.

For the Love of the Game

FOR THE LOVE OF THE GAME

July 2025

For the Love of the Game

A baseball academy teaches all the fundamentals - especially character

By Ross Howell Jr. • Photographs by Tibor Nemeth

Scott Bankhead, a former Major League Baseball pitcher and founder of the North Carolina Baseball Academy, threw his first pitch for his Little League baseball team in Mount Olive when he was 7 years old.

“I enjoyed everything about the game,” Bankhead says. “I loved throwing the ball. I loved hitting the ball.”

Back then, there weren’t many professional games broadcast on TV during the summer. And there were hardly any special coaching camps.

But Bankhead was encouraged along by his older cousins, who played for a regional American Legion Baseball amateur team.

Bankhead went on to throw a lot more pitches — first, for his elementary school coaches in Reidsville, where his family moved when he was 9, then for the Reidsville Senior High School baseball team, then as a collegiate player at UNC-Chapel Hill, and finally, pitching for the Kansas City Royals, Seattle Mariners, Cincinnati Reds, Boston Red Sox and New York Yankees during a 10-year professional career.

After his retirement, Bankhead felt a real passion to pass along his knowledge and affection for the game and dedicated his post-professional baseball life to mentoring young players, both on and off the field.

Bankhead saw a need for better instruction at all levels of the game. He wanted to provide a resource for players of all ages and ability levels, a place where he could have a positive influence on them as athletes and as individuals.

The result?

NCBA, established by Bankhead in 1998.

Located near the Piedmont Triad International Airport, the academy’s facilities are impressive. The campus comprises 12 acres and provides students with indoor- and outdoor-training areas for both baseball and softball, an instructional center, a weight room, indoor pitching mounds with retractable batting cages, performance stations, an artificial turf running track, and a pro shop for equipment.

Students even have their hitting and pitching stills analyzed by Rapsodo and Blast Motion, the same technology used by all 30 MLB teams and 1,200 colleges.

“The philosophy here is to teach the fundamentals of the game,” Bankhead says. “That’s what we do day-to-day at the facility.” And then adds, “Our goal, first and foremost, is to enable players to do well in school, so they will be able to get into college.”

While state-of-the-art facilities and technology are important, the character, quality and experience of the academy’s instructors are essential.

And NCBA coaches have strong Greensboro ties.

Jeff Guerrie, assistant director of NCBA, moved from Florida to Greensboro during his senior year and played baseball at West Forsyth High School before playing for Greensboro College. He coached at Page High School before joining the academy and combines traditional coaching with his expert use of modern baseball training technology.

A graduate of High Point Central High School, Colin Smith played college baseball at North Carolina Central University, Southeastern Community College and Guilford College. He served as head coach of the Lexington Flying Pigs in the Old North State League and teaches NCBA students at all skill levels.

Shane Schumaker played baseball at UNCG and professionally in independent leagues. He returned to coach at UNCG, and later coached both baseball and softball in California. He was an associate scout for the Atlanta Braves before joining NCBA, where he teaches baseball and softball skills — including softball pitching.

A former baseball player at Grimsley High School, Winston-Salem State University and Guilford College, where he completed his degree, Saunders Joplin works with players of all ages, specializing in hitting, catching, pitching and basic skills.

Devin Ponton also played his college baseball at Guilford College. He is currently the head junior varsity baseball coach at Southwest Guilford High School in High Point. With years of baseball experience and knowledge, he coaches players in any area of the game.

To all these instructors, Bankhead drives home the point that personal attention is key to the academy’s success.

“We treat each player as an individual,” says Bankhead. “We help them learn to enjoy the game and to understand that hard work in baseball can lead to success in other endeavors.”

Players can sign up for one-on-one lessons with a coach by appointment. These sessions are tailored to the player’s specific needs — including hitting, pitching, catching, fielding and basic skills.

Coaches also lead training camps throughout the calendar year that offer instruction, drills and practice routines mirroring professional baseball training methods. The goal is to help players gain knowledge, skills and confidence to take them to a higher level.

Finally, there are the NCBA Golden Spikes teams.

The academy’s Golden Spikes program is recognized as one of North Carolina’s premier player development and college prospect initiatives.

Teams are selected through tryouts and bring together the region’s top talent to compete against some of the strongest teams in the nation.

There is a development program for elementary and middle school age players and a college prospect program for high school age players.

“Since the inception of our team program in 2002,” Bankhead says, “we’ve placed more than 100 players at the college or professional level.”

Producing that number of elite players certainly gives Bankhead bragging rights.

But he’ll tell you that’s not the endgame.

Recently, he was out on the golf course and ran into a former NCBA student he remembered well.

This one had gone on to play college baseball and then earned a medical degree.

“Now, he’s a vascular surgeon,” Bankhead says with a smile.

“Sure, we like to see our students reach the highest levels of professional baseball, if that’s what they want,” he adds. “But we’re also a resource for the future doctors of the world.”

Wandering Billy

WANDERING BILLY

July 2025

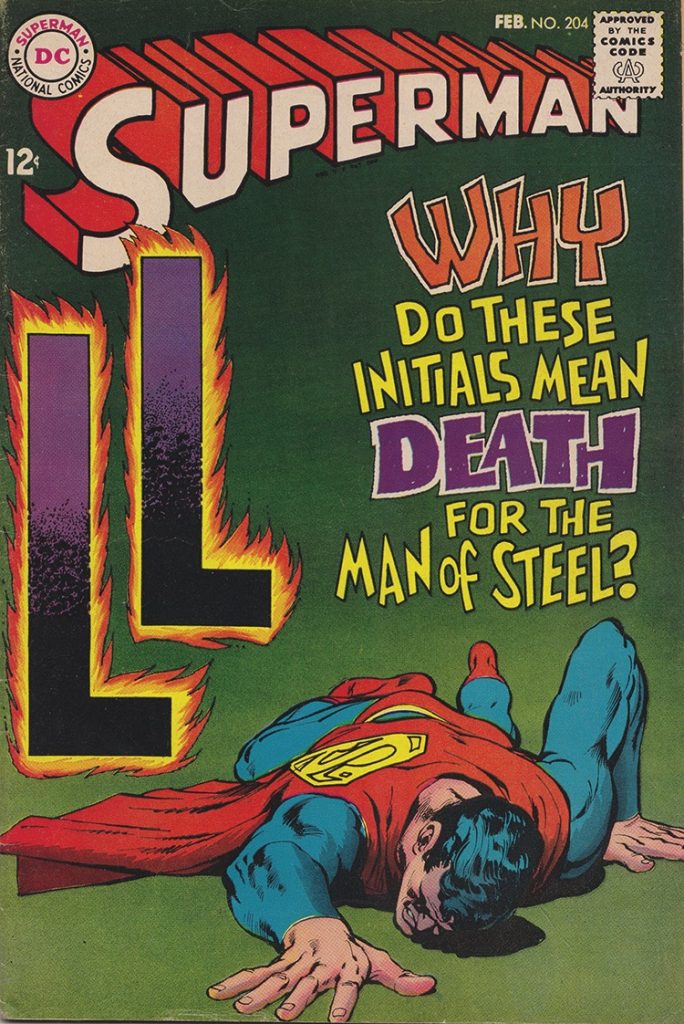

Who Killed TV’s Superman?

A chance encounter may have revealed the answer

By Billy Ingram

“In the future, everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes.”

— Andy Warhol

Life’s stopwatch began ticking off my 15-minute strut across its proscenium in 2002, upon the release of my first book, TVparty! Television’s Untold Tales, a look at classic TV shows produced during that medium’s messy adolescence. In January of 2003, my publisher had positioned me at The Hollywood Show, a twice-yearly weekend event in North Hollywood, where former 1960s child actors such as Butch Patrick (Eddie Munster) and Jody Whittaker (Family Affair) as well as assorted soap opera and ’80s sitcom luminaries gathered to meet fans and sign autographs.

There was only one celebrity in attendance I was interested in meeting, so I made a beeline to Noel Neill. One of TV’s first single, working “gals,” thanks to afternoon reruns of The Adventures of Superman throughout the ’60s, Noel Neill’s portrayal of that “pesky reporter from the Daily Planet,” Lois Lane, became enshrined in Boomer minds, legendary like Lucy and Ethel. I presented her with my book, opened to the sordid story surrounding the death of George Reeves, who portrayed her Superman in the television series. Illustrated with a screen capture of her star-crossed co-star, Neill gazed at the photo wistfully for a moment then sighed softy, “Oh, George . . .”

Months later, I was confronted with a possible answer to one of Tinsel Town’s most enduring mysteries: Was George Reeves’ death a suicide or murder?

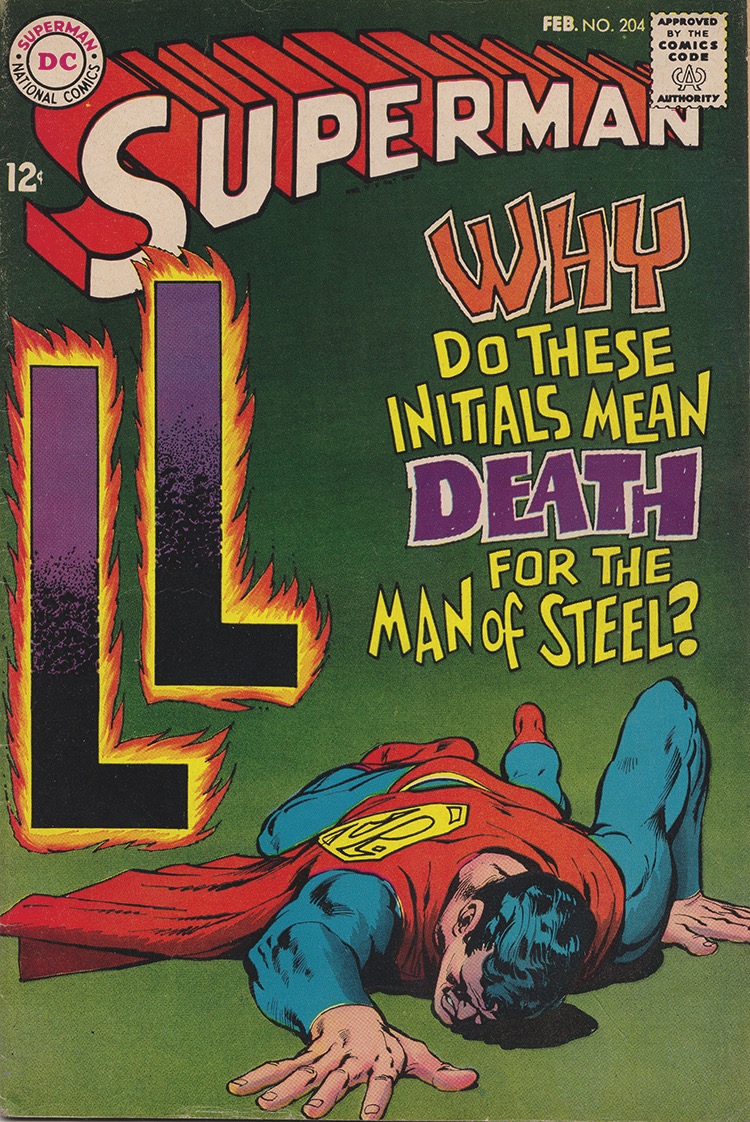

Almost every aspect and detail of the following story is contradicted by someone or other so buckle up: At 1:15 a.m. on June 16, 1959, Reeves, his fiancé, Lenore (Leonore) Lemmon, and two guests were drinking heavily at the actor’s home before he went upstairs to sleep. Moments later, the partiers told police a shot rang out and Reeves was dead, sprawled on his bed naked with a bullet hole through his right temple. Faster than a speeding bullet, Reeves’ death was ruled a suicide.

Lemmon offered no explanation as to why police weren’t called until around 45 minutes after the incident. Following an autopsy, LAPD Chief Parker stated he “was satisfied with the verdict” of suicide. So, why were two detectives still rummaging around in Reeves’ bedroom looking for yet more bullet holes? The two they found embedded in the wall were explained away by Lemmon as earlier recklessness on her and Reeves’ part. And Lemmon had fled to New York, never to return.

Exactly how many stray slugs were dislodged from that room is anyone’s guess, but Noel Neill once revealed, “I had a friend whose husband was later hired to repair the drywall in George’s bedroom. He said the place was riddled with bullet holes.”

Lemmon’s account (one of them, anyway) proved perplexing: After a night of drinking with Reeves and others, she was alone downstairs when, around 1 a.m., two tipsy guests arrived. Their revelry prompted Reeves to awaken and storm angrily downstairs. After everyone apologized, Reeves returned to his bedroom. That’s when Lemmon maintains that she quipped, “He’s going upstairs to shoot himself . . . he’s opening the drawer to get the gun.” When the shot was heard, Lemmon remarked casually, “See there, I told you; he’s shot himself.” Subsequently, she told police she was “only kidding” and, years later, claimed none of that happened.

No secret, Reeves was depressed about being typecast in 1959, but, in recent weeks, he’d signed on for a movie in Spain. Plus, Kellogg’s had secured him, with a hefty raise, for another season of The Adventures of Superman in 1960, even agreeing to let him direct several episodes.

If not suicide, who would want George Reeves dead? He’d recently ended a seven-year affair with Toni Mannix, the wife of Eddie Mannix, a very powerful MGM executive known as “The Fixer,” whose mob and political ties could disappear any problem. Toni had purchased Reeves’ house, car and clothes for him, and was left devastated when their relationship came to a halt in 1958. Lemmon claimed the jilted lover was ringing up Reeves repeatedly, day and night, for months before his death. Had Eddie Mannix ordered a hit to avenge his wife? He certainly could have and was considered the most likely suspect, excluding suicide.

Reportedly, one of those guests that night confessed to a close friend that, after the shooting, Lemmon ran from upstairs saying, “Tell them I was down here, tell them I was down here!” A neighbor approaching Reeves’ front door that fateful hour hesitated when, observing through a window, he saw the couple engaging in a heated argument moments before hearing a single gunshot.

I discovered this just a few weeks ago. In 2021, Lee Saylor published, Wild Woman: Lenore Lemmon, extrapolating from two 1989 phone interviews he conducted with Lemmon mere months before her death. Through impressive research, the portrait he paints of the socialite after Reeves’ death was of a woman who returned to nightclubbing before becoming a reclusive alcoholic.

This portrayal was significant because it corroborated a backstory told to me in 2003, again in Los Angeles when I was promoting TVparty!, this time at Bookstar in Studio City. Regaling an audience with stories from the anthology, I noticed, from the corner of my eye, a woman feigning interest in whatever publications she was picking over but clearly intently listening after I began speaking about Reeves’ demise.

The bookworms dispersed and an attractive woman in her 30s, with a “black sheep of the family but still in somewhat good graces” vibe, emerged from the stacks. “I knew Lenore Lemmon in New York,” she told me. “I used to stay up late nights drinking in her penthouse, listening to her talk.” As I recall, she told me that her family lived in the same building as Ms. Lemmon and, over time, the young woman gained Lemmon’s confidence and ultimately became a drinking buddy.

She related to me that Lemmon had become a recluse, burying disappointments beneath bottles of bourbon and cartons of cigarettes. During one or more of their midnight meanderings, Lemmon confessed to being responsible for George Reeves’ death, but never elaborated. This person only approached me because she happened to be in the shop and heard me talking about her one-time acquaintance.

Very convincing, but could I believe her? It wasn’t common knowledge in 2003 that Lemmon had spent a decade or so in an alcoholic haze prior to passing. Saylor’s book depicts the Lemmon described to me in that bookstore encounter.

Mystery solved? Hardly. Without knowing the identity of the woman I met at Bookstar, there’s no way to verify her (or my) tale of Lemmon’s late-night, late-in-life confession. I’m convinced the unidentified woman would have gone public if she was attempting to insert herself into this narrative. Nor am I; a more opportune time to reveal a story like this would have been in 2003 when I began writing and appearing on shows for VH1.

Great Caesar’s ghost! Yet another ultimately unsatisfying layer of intrigue surrounding one of Hollywood’s most enduring mysteries. On the other hand, applying Occam’s Razor, naturally Lenore Lemmon would be the most likely culprit, considering that, in the comics, Clark/Supes was plagued in myriad ways by individuals with double “L” initials: Lois Lane, Lana Lang, Lori Lemaris, Lex Luthor. Lady Luck, it seems, was not on his side.