Happy Campers

Greensboro native Alice Zealy remodels recreational vehicles with verve

By Maria Johnson • Photographs by Amy Freeman

Relaxing on a pale turquoise sofa under a window that frames a soothing mosaic of tree leaves, Alice Zealy and Eric Ellington are the picture of domestic tranquility.

Across the room, a 50-inch flat-screen TV murmurs country music videos. A ruddy dog named Ruby snoozes on the couch beside Zealy. A larger black-and-white pup named Dega — as in NASCAR’s Talladega Superspeedway — sprawls on a faux-fur dog bed that meshes perfectly with the room’s teal-white-and-gold color scheme. Zealy describes the couple’s aesthetic as sleek, modern and whimsical. A slim round antique table, adorned with a band of metal filagree, stands nearby. Colorful fish swim across the wall. Two clear, acrylic bar seats snuggle up to a counter. A gilded sunburst mirror reflects the morning sun.

It matters little to the couple that their home encompasses a grand total of 350 square feet, rolls on wheels and hitches neatly into the bed of a hulking GMC pickup truck.

“This is probably my favorite home ever,” Zealy says, smiling at Ellington.

“Me, too,’ says Ellington, smiling back.

They’re two happy campers.

Zealy started her business, Rain2Shine Ventures, earlier this year. Her public — meaning her Instagram and Facebook followers — fairly demanded it after she spent much of COVID’s darkest days remodeling her own camper and posting starkly different before and after pictures.

“I got about 2,000 likes and shares,” says Zealy, 40, a Greensboro native. “People were saying, ‘This is the nicest remodel I’ve ever seen. It should be in a magazine.’”

Followers drooled over her kitchen and bath upgrades.

Zealy kept most of the original dark wood cabinetry, but transformed it by sanding, priming and using an industrial paint gun to spray on several coats of gleaming white acrylic latex. Dingy vinyl wallpaper got the same treatment.

Up came the ratty, beige carpet. Down went luxury vinyl plank flooring in driftwood gray.

Counters were resurfaced and, in the case of the breakfast bar, fitted with hinged Corian leaves.

Out went the skimpy stainless-steel sinks and dated faucets — in went a porcelain farmhouse sink with gooseneck faucet in the kitchen, while the bathroom got a stylish waterfall faucet and glass vessel sink.

Zealy installed tile backsplashes in both rooms and decked the bathroom floor with gold-trimmed porcelain tile. Real tile, which some RV renovators eschew because of the heft.

Never mind the weight of real tile, Zealy says. Just take out some of the heavy, bolted-down furniture that most campers come with.

“Every camper we’ve ever done, we’ve never put back in as much weight as we’ve taken out,” she says, implying the upward trajectory of her business.

Last month, she was renovating her sixth and seventh clients — quite an accomplishment considering that she had never set foot inside a camper until she was 30 years old.

She came from a “house” family.

Her father, Sam, was a partner in Wrenn, Zealy and Kirkman, a Greensboro real estate and property management business.

Her mother, Jane “Peppermint” Zealy, was a second grade teacher with a keen eye for interior design.

Daughter Alice spent summers helping the family business by cutting grass, sweeping stairwells and managing yard sales stocked with the belongings of vanished and banished renters. As a sideline in high school, she made jewelry for family and friends.

After taking design courses at N.C. State and UNCG, she worked at the Belk department store in Friendly Center. She started by selling shoes, worked her way up to management and found her bliss in visual merchandizing.

She also incorporated her jewelry business, Alice’s Chic Boutique, which caught the eyes of vendors who supplied gift suites for the Emmy and Golden Globe awards. They invited her to design jewelry that would be given to celebrities.

“The idea is that someone wears your jewelry, they tweet about it and you get the brand awareness,” Zealy says.

Actress Angela Bassett, an Emmy nominee in 2013, wore one of Zealy’s pieces, a lacy black cut-out necklace, at a benefit gala that year.

The Hollywood exposure earned Zealy a few minutes of fame. The local newspaper and a couple of television stations sent reporters to interview her.

A woman approached Zealy in Friendly Center and asked if her distinctive necklace was a piece by Alice.

“Uhhh, yeah,” said Zealy, who was taken aback. “I’m Alice.”

“Oh, my God!” swooned the woman.

Zealy laughs at the memory, putting a hand to her chest in mock admiration of herself.

“I was like, ‘Am I the Michael Kors of Greensboro?’” she says, invoking the name of a popular jewelry designer.

Zealy led a comfortable existence. She and her then-husband lived in a 3,700-square-foot home with a swimming pool off Westridge Road. They traveled frequently in a camper, the first one Zealy had ever set foot in, to watch NASCAR races.

When the couple split, he bought her share of the camper.

Not knowing what she wanted to do — other than be free to travel — Zealy took the settlement and bought another camper that was advertised on Facebook Marketplace. By then, she had visited 20-some campers in-person and had viewed hundreds online.

Ellington went with her to check out a 2003 Holiday Rambler, a so-called fifth wheel because the trailer attaches to a U-shaped hitch, or fifth wheel, in the bed of a truck.

Inside, the camper was — to use Zealy’s word — nasty. Surfaces were yellowed by cigarette smoke. The carpet was stained and reeked of dog waste.

But structurally the camper was in good shape, and the motorized slides that expanded the trailer sideways when parked — two slides in the living room and one in the bedroom — worked fine.

“It’s a really well-built piece,” says Ellington, 58, a NASCAR team veteran who owns Ellington Rod & Custom, a shop that builds street-legal hot rods in Archdale.

Zealy sealed the camper deal with $7,500 cash in February 2020, and they towed the Rambler to Ellington’s shop, where Zealy worked for six or seven months to transform the camper into the RV of her dreams.

Ellington, her new partner in life and work, made sure the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems functioned well, while Zealy exercised her artistic ability.

“I got the freedom to do what I wanted to do,” she says.

Ellington supported her, expecting that he would enjoy the outcome.

“I said, ‘Whatever you want to do,’” he says.

“I make things pretty, and he makes things work,” she adds. “But I’ve learned a lot. I can make things work now, too.”

“Absolutely,” he says, smiling at her.

Zealy took her time, carefully documenting her improvements on Facebook and posting links to the sources of her material. She felt no pressure to wrap up.

“There was nowhere to go because of COVID,” she explains.

When she finished the transformation, she and Ellington ditched their plan to buy land in the country, install electrical and plumbing hook-ups for the camper and eventually build a house on the property.

They decided to live in the camper. Full time. They rented an annual spot and a bought a membership in the Thousand Trails campground in Advance, near the Yadkin River.

The campground — which boasts two swimming pools, volleyball courts and horse trails — is part of a national chain of campgrounds.

They can afford to travel more. Their scaled-down lifestyle sips income.

Monthly expenses run $350 to $400, says Ellington.

He’s elated at the change. He used to live on a small farm in Gibsonville.

“If I wasn’t working at the shop, I was feeding horses and chickens, and bush-hogging pastures, and getting up hay,” he says. “I always wanted to go and see.”

Now, he and Zealy are part of a recreational vehicle boom that started before COVID and gained steam during the pandemic. Camping allowed for social distancing, and more people worked from home, wherever that happened to be.

“If the job allows you to, why wouldn’t you?” says Zealy. “You see more young people, rather than retired people, coming into campers and vans now . . . This generation — I call them the Instagram Generation — they want the experiences.”

“They want good pictures,” Ellington adds with a smile.

Zealy sensed an appetite for splashier RV interiors, and she saw that very few businesses specialized in that kind of design. Some RV repair shops offered remodeling, she says, but fashionable upgrades were not their forte, and they charged more than she intended to.

As COVID waned, Zealy launched her business.

She named it Rain2Shine Ventures after the nicknames that her father, Sam, who died in 2007, gave her and her sister, Mary Knox: Rainbow and Sunshine, respectively.

“He would have loved to be here, doing this with me,” Zealy says. “He was Mister Handy. He could do just about anything.”

She carries on his spirit in her work.

“There’s times when I’m out there, in the campers by myself, that I talk to him,” she says.

For a young couple in Wagram, N.C., she’s upfitting a Winnebago with heavy duty dog kennels. The couple will use the vehicle to transport rescue dogs.

“My goal is to make it nice enough that they can do adoption fairs on the bus,” says Zealy, a supporter of the rescue organization. “We’ll paint and do little paw prints. It’ll be beautiful. I want it to be happy.”

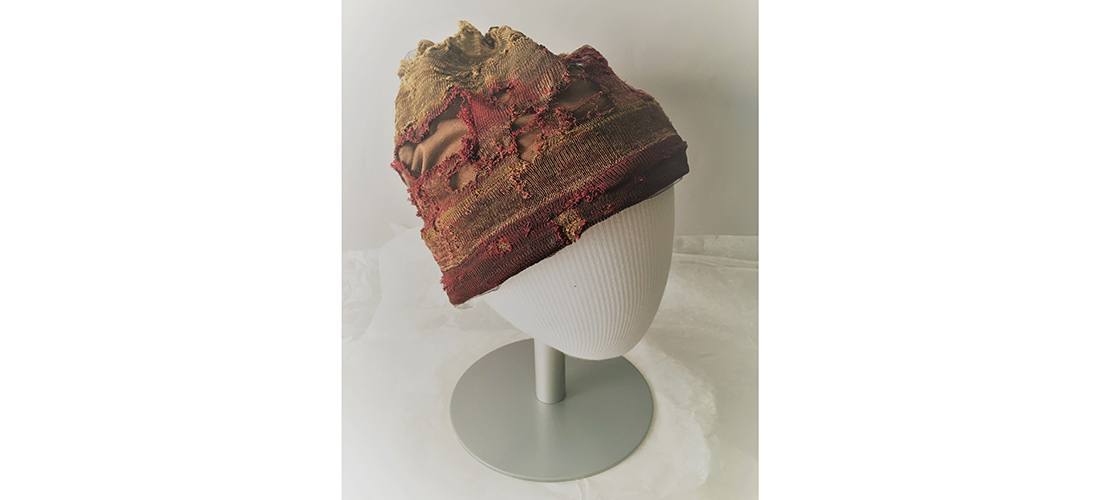

For another customer, a friend, she’s reviving a tiny, British-made 1969 Sprite camper.

“It was just a hull of parts,” says Ellington, describing the vintage trailer’s condition when Zealy’s friend bought it. “I think she gave $250 for it.”

“It’s gonna be adorable,” Zealy promises. Sitting in her favorite home, she’s as radiant as a rainbow. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. Email her at ohenrymaria@gmail.com