Home Grown

HOME GROWN

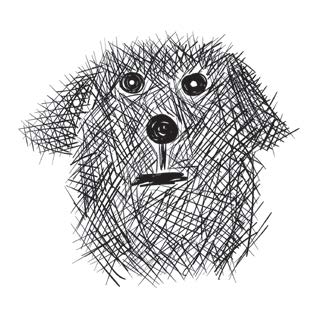

Max

The making — and unmaking — of a miscreant

By Cynthia Adams

Our rescue — let’s call him Max — has a record. I worry he might be sent to juvenile hall. Or reform school for troubled terriers.

I’ve changed our wire-haired fox terrier’s name to protect his identity should an overzealous public servant decide to pursue any of his perceived crimes.

Max has never gained a firm grasp on boundaries. Now, skittering around on the margins of civil society, he is a wanted canine. Why? He bit the hand that feeds him.

But first, a little background: Max, a “high-energy” dog, was foisted off on me in the paint department of a Lowe’s at the North Carolina coast. His owner, a bedraggled looking mom of children of various ages, said he stole the little ones’ rubber ducks. He had been banished to a pen in their backyard, where he had been confined for four years. She produced a picture on her cellphone: Max, a tan-and-white beauty, looked straight at me from the photo with the saddest of eyes.

From another picture, he pants breathlessly out of a passenger window, beckoning me with a “please” look in his eyes.

I later learned that two large labs lived indoors while little Max, just 14 pounds, was penned alone in the backyard. Was he underfed, too?

When we brought him home Max was so jubilant, given his newfound freedom — a dog door and fenced yard to roam — it took him weeks to settle down even a little. As forewarned, he was petrified of storms after years of suffering through them alone. Is it possible for a dog to be phobic about rain yet adore water if it doesn’t fall from the sky? Inscrutably, he loves to splash and play in water but dashes in through the dog door at even the gentlest rain.

Max was not only jealous of our smaller, younger dog, he was a thief, stealing any toys from man or beast.

But with time, effort, consistency and affection, Max possessed moments of calm that gave us a glimpse of his future self. He gained a few pounds, showing a taste for carrots and fresh apple.

Even so, five years later, he remains neurotic to the point of terror with the slightest threat of a storm, near or far. Soft jazz helps. Medication doesn’t. He tunnels underneath the sofa, shivering until the storm passes. And yet, the mere glimpse of a water hose sends Max into a rapturous, manic, playful frenzy.

He is a creature of the morning; by evening, he prefers to be left alone in his bed, more curmudgeonly.

Yet he is exceedingly smart, able to reason and anticipate. When Max sees me sorting glass, he anticipates a car ride to the recycling center and is sent straight into a an ecstatic, hyper state.

One late afternoon when Don and I were walking him, he suddenly lunged for something on the ground. “That could be a chicken bone!” I cried, given fast-food remnants littered the area.

Don pulled Max’s leash in, hurrying to open his mouth and fish out the foreign object; Max clamped down firmly on the soft tissue between his thumb and forefinger.

When Don shouted in pain, Max clamped harder in resistance. He was not surrendering his prize.

By morning, Don’s hand was purply and swollen. Our physician was away, so he visited a clinic. The attending physician shook his head, returning with a clipboard. An official dog bite report was made to Animal Control even though Don’s injury only required precautionary antibiotics, a cursory look and rebandaging. No stitches.

State law requires that a dog who has bitten a human — even their owner — quarantine for 10 days for rabies observation. (This includes fully vaccinated canines.) Guidelines require the animal sequester at a veterinary hospital, animal control facility, or, possibly, the owner’s property. There is no exception for first-time offenders like Max.

I gasped: How would Max survive should they order confinement at the shelter? Or the vet? This was a dog whose spirit had only been restored after years of effort. He had suffered banishment once. He might not have the resilience to handle such isolation again.

Home confinement looked wonderful by comparison.

We chewed our nails, waiting for Animal Control to knock at our door. In desperation, I displayed a published article I’d written for this magazine about Max’s first year with us. In it, he was sitting happily at his master’s side, flashing a cheery doggy smile.

We eventually resumed walking him, strictly on a shorter leash. We reasoned it was a bad idea to come between food and Max, who had possibly been underfed those many years of confinement.

Weeks, then months passed. We exhaled. Thankfully, Mad Max got the third chance he deserved.