Sazerac May 2025

SAZERAC

May 2025

Just One Thing

For Celena Amburgey, home is where the art is. “By intertwining paint, mixed media and deeply personal items like my daddy’s bed sheets, my work becomes a vessel for layered narratives,” says the creator of Blue Ridge Venus, which combines oil paint, vines, Mason jar rings, love letters from her father and a childhood bedsheet. “These intimate objects carry the weight of my heritage,” says the artist, who hails from Jefferson, N.C. Utilizing both personally precious as well as oft-discarded items such as plastic bags and grocery sacks, she says, “I craft a powerful dialogue on the tension between what is cherished and what is disregarded, drawing attention to how we assign worth and value in our lives.” Amburgey’s works, along with art by two other M.F.A. candidates, Paul Stanley Mensah and Nill Smith, will be on exhibit through May 25 at Weatherspoon Art Museum. Meet the artists on Thursday, May 8, from 5:30 until 7:30 p.m. Info: weatherspoonart.org/exhibitions/current-exhibitions.

May 25 Unsolicited Advice

If, like the rest of us, you’re trying — but struggling — to break up with your smartphone, this one’s for you. Those little buggers are full of dopamine hit after hit, lighting up our brain in a way that screams, “More, more, more!” When we find ourselves in a moment of quiet inaction, our fingers wander to that tempting touchscreen, desperate to fill the void. Well, we’ve come up with some digital-free ways to occupy those digits while taking a note from Depeche Mode: “Enjoy the Silence.”

Get hooked on something new: Learn to crochet. If you start now, you’ll have an entire collection of colorful hats to gift friends and family during the holidays.

Play solitaire. And not on an app, but with a real, tactile deck of cards. Best part? No one will ever know if you cheat — not that we’re endorsing that behavior. We just have the luck of the draw.

Try your hand at building. Scandinavians are consistently ranked among the happiest in the world and it’s probably because they’re constantly creating with Legos, which originated in Denmark, or putting together Swedish-made Ikea furniture. We certainly smile — through gritted teeth while cursing — when we assemble a Kallax shelf.

Read. As the proverb goes, “A book in the hand is worth two in your library queue.” Or something like that.

Window on the Past

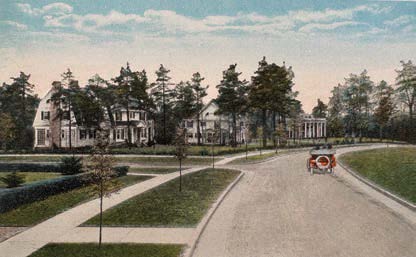

Though much of Greensboro has changed over the years, the charming facade of this Irving Park Dutch Colonial, the historic R.J. Mebane House, remains very much the same since its circa 1912–13 construction. Wondering about the interiors? See for yourself as this and many other Irving Park abodes throw open their doors, welcoming guests of Preservation Greensboro’s Historic Tour of Homes, May 17 and 18. History, architecture and design come together to help you reach your step goal. What more could you want? Tickets and info: preservationgreensbo.org/events.

Must Love Books

Reading, writing and arithmetic? No, thanks on that last part of the equation. The Greensboro Bound Festival is where reading, writing and book fanatics create a buzz of all-day literary activity descending upon the cultural epicenter of downtown Greensboro.

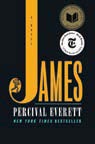

But first, at 7 p.m. on May 15, how ’bout a little pre-fest fun with . . . (if this were an audiobook, you’d hear a drumroll right now) . . . Percival Everett, The New York Times-bestselling author of several novels, including the 2024 National Book Award for Fiction winner, James? A reimagining of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, James is told through the eyes of the runaway, enslaved Jim. Everett is sure to draw a huge crowd, filling up UNCG’s Elliott University Center Auditorium. Registration is required — and is now waitlist only — by May 12 and can be found via the Greensboro Bound website.

Now, hold onto your pen caps and block out May 17 in your planner because this year’s one-day festival is, well, one for the books.

Dreaming up your own manuscript? Learn every trick in the book at the Greensboro Public Library. Three O.Henry magazine contributors, plus a few local notables, help you sharpen your skills — and pencils. Our founding editor, Jim Dodson, teaches “The Art of Memoir” — something he knows a little something about after writing Final Rounds, a New York Times-bestselling memoir. Maria Johnson hones your humor and Ross Howell Jr. shows you how to easily slip between fiction and nonfiction writing. Poets Ashley Lumpkin and Elly Bookman, plus Chapel Hill-based cookbook author Sheri Castle know how to measure for success.

In the Greensboro Cultural Center’s Van Dyke Performance Space, take a page from several authors in conversation. O.Henry editor Cassie Bustamante, yours truly, interviews Winston-Salem’s New York Times-bestselling author, Sarah McCoy, and Reidsville’s Sir Walter Raleigh Award winner, Valerie Nieman, about making herstory with historical fiction. Former Wall Street Journal writer Lee Hawkins, whose 2022 nonfiction book, I Am Nobody’s Slave: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free, was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, chats with Aran Shetterly, author of the harrowing account of the KKK vs. Civil-Rights demonstrators, Morningside: The 1979 Greensboro Massacre and the Struggle for an American City’s Soul. Andy Corren, whose Dirtbag Queen: A Memoir of My Mother was born out of the obituary he wrote for her that went viral, chats with Cassie. Finally, wrap up your evening with a conversation between Christopher A. Cooper, author of Anatomy of a Purple State, and spiritual writer, preacher and community cultivator Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, moderated by Raw Story investigative reporter Jordan Green.

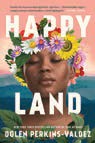

Beyond the Greensboro History Museum’s doors, Kristie Frederick Daugherty, known for her book of Taylor Swift-inspired poetry, and UNCG M.F.A. alum Elly Bookman, plus local high school poet laureates read and discuss their modern take on the ancient art form. Known for her New York Times bestsellers Wench and Take My Hand, NAACP Image Award-winning author Dolen Perkins-Valdez chats about her latest book, Happy Land, which hit the shelves last month.

And what’s a festival without something for the littlest readers and aspiring writers? The second floor of the cultural center is chock full of children’s authors including Kamal Eugene Bell, Natasha Tarpley and Patrice Gopo.

Sage Gardener

“Wait,” says our hiking companion at the head of our group. “You’re saying that bees are not native?”

“Honey bees,” our citizen-scientist hiker responds. “It’s honey bees that are not native to the Americas. But there are hundreds of species of native bees.” (More than 500 in North Carolina alone, in fact.)

“How about honey,” the disbeliever shoots back. “Are you telling me that the honey I put on my toast in the morning is a non-native species?”

“The bees that gathered and regurgitated it are originally from Europe, brought over here to pollinate the Colonists’ crops in the 1600s,” says our apiculturist.

“Yeah, I read that the Virginia Company brought hives over when they established Jamestown,” pipes up the group’s historian. “So, yes,” says our honey bee detractor, “the honey comes from the U.S.A. — unless it’s imported from India, Argentina or Brazil, like a lot of cheap honey is.”

To say that our trail discussions are often lively is a gross understatement. At least it’s not politics this time around, I think to myself.

“I’m going to look that up,” our lead hiker says, an all too common refrain on these hikes. Moments later, Siri chirps, “Here’s an answer from gardenmyths.com: ‘The honey bee is a non-native import into North America and most other countries.”

“But honey bees pollinate our crops,” our dissenter insists. “Without them we would starve!”

Citizen scientist says, “A lot of crops are now engineered to be self-pollinating or even wind-pollinated. I’ve grown tomatoes in my living room with no bees and I still had tomatoes,” she counters. “Besides, a big hive of honey bees can outcompete native bees, sometimes the sole pollinators for certain native plants. Without that bee, the plant can go extinct.”

You can read all about it in our Raleigh sister publication, Walter (waltermagazine.com/home/the-buzz-north-carolina-coolest-native-bees) in a piece by Mike Dunn, a Chapel Hill naturalist and educator. “Our native bees are truly bee-autiful and bee-zarre,” he writes. Plus, he points out, practically no one ever gets stung by native bees.

Or dive into the N.C. State Extension Service’s The Bees of North Carolina: An Identification Guide, available online (content.ces.ncsu.edu/the-bees-of-north-carolina-identification-guide), where you can see stunning photos of wood carder bees, rotund resin bees, cuckoo leaf cutter bees, zebra cuckoo bees, along with scintillating anatomical diagrams.

A whole ’nother subject is plants that nurture and support native pollinators. In March of last year, the Greensboro City Council adopted an official policy to promote native plants and eliminate invasive plants at city-owned facilities.

“Native plants help maintain, restore and protect the health and biodiversity of local ecosystems, supporting native pollinators, birds and other wildlife,” the City proclaimed. The Guilford County Extension Master Gardener volunteers couldn’t be more enthusiastic about those plants our native bees love, sponsoring periodic workshops on them. On Saturday, August 23, from 10 a.m. until 1 p.m. (guilford.ces.ncsu.edu/2025/02/2025-great-southeast-pollinator-census), they plan a count’em-if-you-got-them session as part of the the Great Southeast Pollinator Census.

Meanwhile, detractors of honey bees — especially lovers of native wildflowers like our citizen-scientist hiker — continue to blast Apis mellifera, that European intruder to our shores. One enthusiast at ncwildflower.org/honey-bees-friend-or-foe suggests, “Do not buy honey. Kill any wild hives you encounter. And discourage the use of domesticated hives transported to pollinate crops.”

Y’all bee careful out there, now. — David Claude Bailey