Late in December, O.Henry colleague David Bailey sent a riveting text from a state park in Alamance County. An avid hiker devoted to natural places, he shares his discoveries, photographing flora, fauna, mossy streams and waterfalls. But that winter’s day, he made a surprising find.

He stumbled across a tin metal box emblazoned with the words “Remains of Mrs. Brown” with the cryptic “by Googe” below.

The discovery set my imagination afire, as I just so happened to be gathering information on natural burials and all the alternatives.

Bailey left the remains undisturbed. He conceded that it could be a prank, meant to trap the curious. (Having once found a pink purse at a gas pump one evening filled with human waste, I could hardly argue.) Mrs. Brown, Bailey remarked dryly, could be a punny metaphor for the same thing.

In any event, moving the box was tantamount to disturbing a gravesite and he decided to let it rest in peace.

But I had a different point of view. Who was Mrs. Brown, I wondered, and why were her remains left carefully, sealed inside a box in the woods?

Was there foul play?

I briefly considered trekking into the woods to search for the confounding box, but it was mere days before Christmas. Perhaps Bailey was right — perhaps this was a memorial honoring Mrs. Brown’s final wish.

I flashed to the natural burial site known as All Souls Natural Burial Ground, which I had recently visited in the fall. It differs from any cemetery you probably know. Yet there is nothing unnatural about All Souls. It simply fulfills the most instinctive of impulses. Rather than embalming and sealing our dead inside coffins — or vases — for perpetuity — All Souls allows the body to rejoin the elements in the quietest of settings.

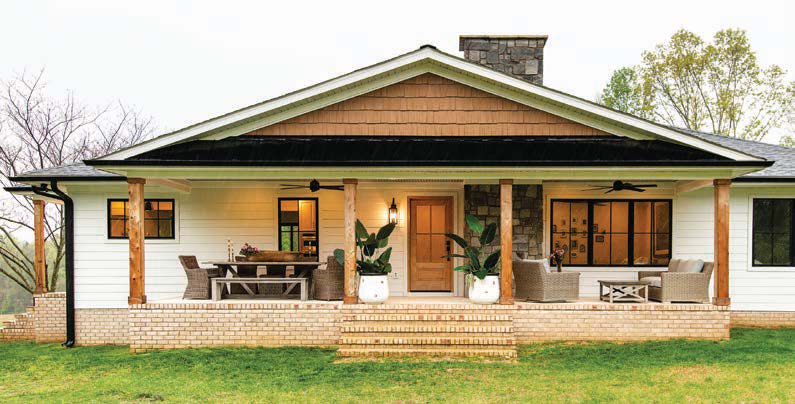

All Souls occupies 3 acres of wooded terrain in Guilford County. Located on a site adjacent to St. Barnabas Episcopal Church on Jefferson Road, it is among several such sites in North Carolina created in response to an increasing awareness of natural alternatives.

Don’t expect monuments and manicured grass. Instead, engraved, ground-level native stones mark individual sites (each recorded with its GPS coordinates), blending with its surroundings.

Those interred at All Souls are buried in their choice of a simple shroud, a box or a coffin made of biodegradable materials, allowing for the natural decomposition of the body.

Ashes to ashes, as the Book of Common Prayer says. Dust to dust.

Mind you, none of this is new. It was the preferred way of our not-so-distant ancestors.

*****

Deborah Parker, board president and family liaison at All Souls Natural Burial Association, consults with those wishing to learn more about natural burial in a paneled meeting room filled with folding tables and chairs at St. Barnabas. In her six years of volunteering, she has sat here explaining their purpose many times over.

Too often, that conversation occurs at the worst possible time. It is far easier when a conversation about final arrangements for our loved ones takes place before any crisis arises, she points out.

According to Parker, Randall Keeney, the retired vicar at St. Barnabas, did all the background advocacy and work to bring All Souls into being. Symbolically, the cemetery opened on November 2, 2019 — All Souls Day. On April 5, 2021, Frederick Westmoreland Jr. was their first natural burial.

St. Barnabas and All Souls have a symbiotic relationship. “The church owns the graveyard. He [Keeney] did a lot of the groundskeeping when he was here,” she explains. By supporting and participating in natural burials, also known as green burials, Parker and a cadre of volunteers, mostly retirees, now provide the manual and emotional labor of running All Souls.

At this writing, 26 people have been buried there and 80 have pre-purchased burial sites.

Parker, the family liaison, has been present for all but three of those burials.

“The American way of death is changing a lot,”

she says.

Blue-eyed and white-haired, Parker’s peasant top, Apple Watch and wire-rimmed glasses convey strength combined with compassion. I see both placidity and firmness, a quality the Japanese call “Goju,” meaning, hard and soft. With a wry grin, Parker says, “I can cry easily, yet tolerate no BS.”

On the face of it, the concept of a natural burial is age-old and the premise is simple. Many elders today still recall a time when their dead were bathed, dressed and prepared for burial at home. A number of my ancestors lie in family cemeteries once dotting rural farmlands.

The movement toward the natural interment of our dead is a return to the practices that were commonplace until the 1800s before the Civil War era. In the early days of embalming, reports of alcohol, arsenic and even gasoline were used to preserve the bodies for transport. On shipboard, prominent personages were “pickled” in casks of rum rather than buried at sea.

Gradually the process of burial was relegated to funeral homes, with restriction and regulations sprouting up.

Today, natural burial means many things — it may simply refer to interment in a family cemetery. It may also mean legally opting out of commonplace burial methods, such as embalming and even the use of a casket or a vault. At this writing, online estimates for basic funeral costs are between $7–10,000, although my personal experiences have exceeded that. Costs of a plot and monument are additional.

But how challenging is a return to a less institutional way of dealing with our dead? While the appeal of a different approach is undeniable, it raises questions. Is the red tape formidable?

Turns out, it is simpler than imagined. Parker’s face sets with resolve. She has now been doing this work for years. Delving into concepts about death — especially natural burials — has become a raison d’être.

In the room where she meets those in the process of making final arrangements for themselves or a family member are examples of basic casket options, including a cardboard version. Some even invite others to help decorate it — like one would have friends sign their cast.

North Carolina law, in fact, offers a number of options for interment, she stresses. Embalming is not legally required. “To me, it is like putting your body through so much disrespect,” Parker observes.

So, it heartens Parker that the funeral industry itself has become a supportive partner with natural burials and has participated in most that she has experienced, transporting the dead and providing storage until interment is arranged. Her daughter, Meredith Springs, is an Asheville funeral director who also advocates natural burials.

Funeral homes also handle required legalities, including generating death certificates. But none are required to be handled by the funeral home, according to state law. (You might want to check out Evan Moore’s recent “Can You Bury a Relative at Home in Your Backyard” in the Charlotte Observer: charlotteobserver.com/news/local/article277022153.html.)

You can legally apply for and obtain a death certificate outside a funeral home, but, she warns, this is daunting. “One of the hardest things to do,” in Parker’s experience.

Nonetheless, “the American way of death is changing a lot,” she notes.

Parker, who lectures widely for civic groups and events, explains that a prevalent, mistaken belief is that the deceased must be immediately removed from the home by a funeral home.

“You can keep the body at home,” she clarifies. “Which gives family members time to be with them.” According to online sources, that time frame is liberal, with few legal restrictions.

In describing personal experiences with her own family, Parker is most affecting. Her brother, Dale Clinard, was the impetus for her “desire and interest to help others have what they wanted” as he prepared his family for his pending death in 1989. He encouraged his family to become involved with the process.

She described the life lessons he imparted, teaching them “no fear of dying.”

At Dale’s death, the family requested a delayed pick up by the funeral home (permissible, she points out), allowing time to bathe and dress him, and affording time with family and friends who visited throughout the night.

“He had such a loving acceptance of death that it made it a lot easier for us,” she recalls.

“He had flowers sent to my parents the day after he died, thanking them for his life,” Parker says, still moved by the memory.

The experience spurred her to become a hospice volunteer, and led to eventual involvement with natural burial. Each year Parker holds her own workshops in the church’s parish hall to guide others who wish for an intimate, involved experience. If they choose not, so be it, she says.

All Souls, which helps coordinate the necessities of burial, has a single fee. A total of $3,500 includes the site, costs to open and close the grave, and a flat, native stone for engraving. “All we do here is receive the body — we call them ‘loved ones’ — and bury them.”

A shroud (many use a natural fabric sheet or quilt) or casket are funeral home expenses but it is legal to provide your own. For those who don’t purchase a shroud or a casket, Parker has personally swathed the deceased in a cotton sheet at the funeral home.

All Souls does require that caskets be biodegradable, hence made of wood, bamboo or cardboard. Willow and seagrass caskets are also accepted — Parker mentions craftspeople at Moss and Thistle Farm near Asheville who commission wicker caskets, which she describes as “beautiful.”

There are no vaults, nor metal, sealed caskets at All Souls.

(There is also no legal requirement necessitating burial 6 feet under, Parker explains. Graves can permissibly be shallower, approximately 3–3.5 feet deep, as is the case at All Souls.)

Others choose cremation. (All Souls does not accept cremains.)

Ashes can be fashioned into cremation jewelry rather than buried at all.

There are other options. One is a process variously called resomation, water cremation or aquamation. Proponents argue it is a greener option than cremation.

Resomation uses water, potassium hydroxide and steam heat to swiftly and fully dissolve the body. At present there are a few resomation chambers in North Carolina, in Charlotte, Hillsborough and Wilmington. Composting is a lesser-known, more green burial option.

*****

Parker is a sort of culture warrior, advocating for straight talk concerning death as a healthier way of living our lives. She says she stands on the shoulders of many who have worked in the realm of death and dying, including artists. She praises a film, The Last Ecstatic Days, made by an Asheville filmmaker.

Approaching death, the subject, a 36-year-old yogi, said, “I am embodied. I am empowered. I am ecstatic.”

The three words were emblazoned on T-shirts.

She mentions how the very culture surrounding death is changing, thanks to his example and others like former intensive care nurse Julie McFadden.

“She became a hospice nurse and wrote a book called Nothing to Fear. It is fabulous . . . She’s got stories about her personal experiences with people that are dying. So, in that book, she talks about the ‘D’ words: Death. Dying. And dead.”

Before parting, she leafs through pictures of natural burials she has participated in at All Souls. She describes loved ones giving eulogies surrounded by the moving, natural sounds of birdsong and breezes. An occasional deer meanders through. Burial sites are covered with greenery and flowers at the end. Parker finds these funerals beautifully evocative, even when she does not know the deceased.

She walks along the rustic grounds and pathways, pausing to discuss various people buried there.

Parker mentions another film, A Will for the Woods.

“Put it on your list,” she advises as we part. “And be sure you have your plans in order,” she adds, shoulders squared, a pensive smile dimpling her cheeks. The title had struck me as poetic in the moment. Yet I had no idea that it would prove prescient.

*****

On February 13, the day before Valentine’s Day, Bailey phoned with an update on the mysterious case of Mrs. Brown.

Returning to the park, he noted police huddled in the parking lot alongside a park ranger, holding the box he had found in December.

The box was firmly welded shut. “Whoever did this went to a great deal of trouble,” Bailey said, slightly short of breath as the police pried the metal box open.

“Say, do you remember when I told you about discovering it?” he asked.

The police talked in the background as we speculated. Absent foul play, surely, if someone wished for their remains to simply be left in the woods, it must be legal.

Actually, no, the park ranger quickly corrected us. It was illegal to dispose of human remains in public parklands.

This was hardly comparable to a natural burial, I was reminded.

Later, Bailey texted pictures of possible fire ashes mingled with what looked a whole lot like cremains and visible teeth and bone fragment. I studied the photos, hoping this was all done in innocence.

The box, now with the medical examiner’s office, remains a mystery. A report has yet to be issued. Bailey returned to his own writing.

“It’s your story now,” he emailed. But of course, it wasn’t.

It was another’s story. Someone — but who? — and their own particular will for the woods.