A Tug to the Tar Heel State

A Tug to the Tar Heel State

Inside the collected and colorful Casa Carlisle

By Cassie Bustamante

Photographs by Amy Freeman

“I f you want to date me, you have to promise we can live in North Carolina one day,” Jason Carlisle recalls his wife, Crystal, saying presciently to him early into their 20-year relationship.

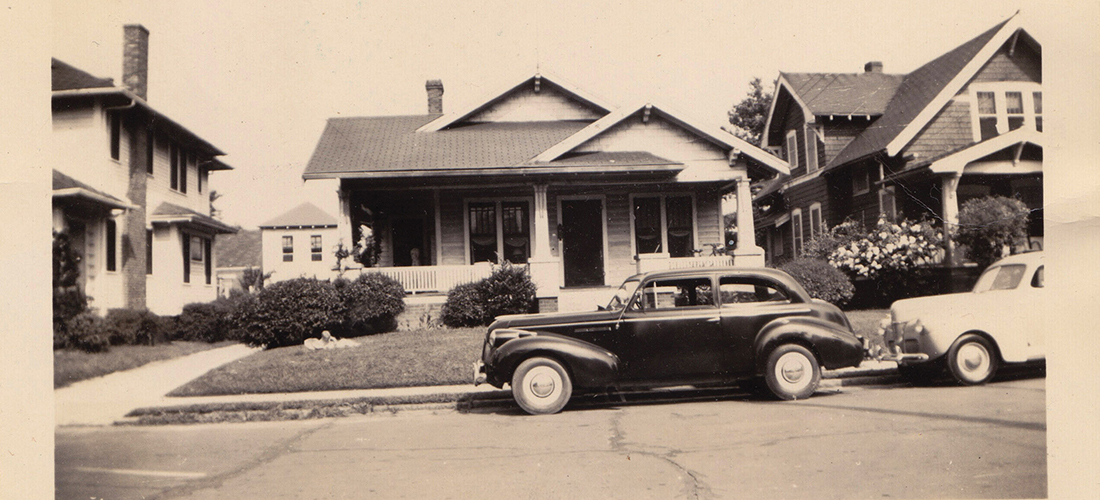

“I don’t remember saying it like that!” she counters, but confirms it was part of the deal. North Carolina, Crystal says, “was woven in my heart long before I knew why.” While she felt an inexplicable pull, Jason, who says he’d follow Crystal to China or the moon, had always loved the Tar Heel State. He recalls fond childhood memories of trips from Florida, where his family had a farm, to Maggie Valley and Cherokee in the ’80s, as well as traveling with youth groups to leadership conferences in Appalachia.

And so it was that in the summer of 2018, the couple and their three boys — Lucas, now 15, Grayson, 14, and Micah, 9 — took a leap of faith. They sold their farm in Florida — “Cows, chickens, I mean the whole farm!” says Crystal. With no new employment prospects in sight, Jason, a teddy-bear type who now works for GFL Environmental in High Point, quit his job and said goodbye to his tractors and truck when the family made the move.

Why? Crystal discovered that her little sister, Karissa, who had been adopted as an infant years earlier by a family in California, was now living in North Carolina. It’s a long story that begins with Crystal’s mother: “My mom had my brother and myself and was a single young mom and found herself pregnant again and gave that baby up for adoption.” It turns out that when Karissa was only 2, her adoptive mother died of ovarian cancer. Her adoptive father moved to North Carolina for familial support. So when Karissa, at 18, reached out to her birth family, Crystal finally understood that tug she’d felt to North Carolina

So, with as many of their belongings as they could fit in a 26-foot U-Haul, the Carlisle family headed north. Awaiting them was a 1971 home (more than double in size of their farmhouse) abutting Forest Oaks Country Club’s golf course.

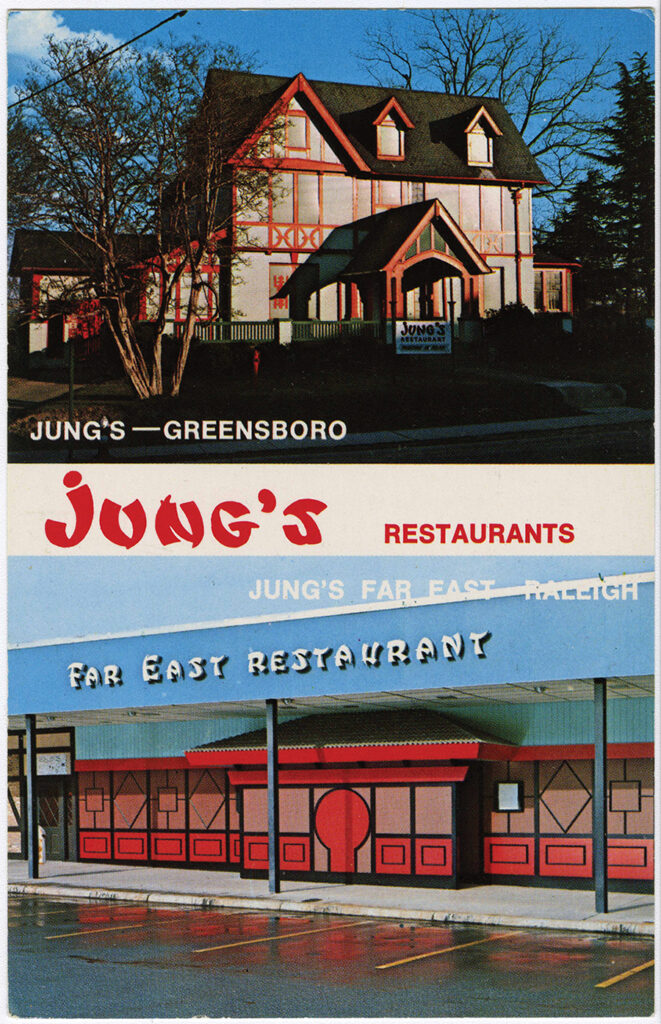

Just months earlier, Crystal had taken a six-day house-hunting trip to the Greensboro area — selected for its proximity to Thomasville, where Karissa lives with her two children — looking at over 20 houses. By day five, she recalls resolving to live in a camper for the summer because nothing felt right and she “was not going to settle.” Finally, on day six of her trip, a Friday, her agent brought her to Forest Oaks.

“I can live here,” she thought, satisfied that the neighborhood was close enough to town, but with a bit of the rural feel her family was used to. The house itself was structurally sound and the kitchen had been updated a couple years earlier by the previous owner, but Crystal — who calls herself “The Thrifty Designer” on Instagram — was excited to wave her creative wand, especially with so much more space to serve as her canvas.

Jason and the kids, of course, didn’t see the new family residence until the day they pulled up in the moving truck, and, as he recalls, he said, “Welcome home, boys. We’re home.”

Arriving with limited furnishings and possessions, Crystal quickly got to work slapping a lot of paint on the walls and filling their new abode with vintage treasures found at various secondhand stores. “I try to live sustainably, for sure,” she says.

In fact, much of the home’s decor is thrifted. Crystal, who formerly owned a vintage shop in Florida, spent childhood weekends and summers with her great aunt and uncle, Jimmy, a regular flea market vendor. “They called him ‘Bones,’” she says. “Because he sold actual bones. Alligator skulls and you know.” Growing up in that environment, she became accustomed to thrifting and has carried that into adulthood. “I never knew anything different.”

In the family’s den, just off the kitchen, Crystal waves an arm around the room and says, “Literally everything in here was thrifted.” Even the leather sectional? Yes, even that, which set the family back a whopping $150. And the floral vintage wallpaper? Also thrifted.

The only piece in that space that traveled from Florida with her is a Modern painting of a woman in blue holding cut roses in pinks and reds that sits between two windows. It was a gift to Crystal from her mother on her 18th birthday. Though it appears as if the colors in the artwork inspired the palette of the room, Crystal says, “I am just drawn to those colors and when I put it up there, I thought, oh my gosh, she’s perfect.”

With bold strokes and an innate sense for seamlessly mixing antiques with Modern vintage, Crystal continues the flowery patterns and color palette throughout the main floor of the home. Blues, teals, pinks and reds harmoniously repeat, masterfully drawing the eye from one treasure-filled room to the next with ease.

How does Jason feel about the florals and pastels that flow throughout the home? “I trust her so much,” he says, a glint of pride sparkling in his light blue eyes. Then, those eyes twinkling, he says jokingly, “As you can see, I inspired everything in here.”

In the dining room, pink paint blankets the walls, creating a soft and intimate surrounding for a looooong wooden table flanked by a contrasting teal antique church pew and midcentury upholstered dining chairs. On one wall, a pair of long shelves display a rainbow assortment of vintage glassware.

“Did she tell you about this table?” Jason asks. “$100!”

The blonde wood table, it turns out, was handmade, complete with turned legs, by a neighbor and features several leaves to make it even longer. She purchased it when his estate items went to auction. “When we moved, I was like, I want a dining room table that will fit 12–14 people and everybody was like you’re insane,” says Crystal. But, she adds, “I put it out there and it comes to me!”

Dreams come true for Crystal. Now, the dining room hosts regular Sunday family dinners with Karissa, her husband, Travis, her kids and her adoptive father, affectionately known as Uncle Earl to Crystal’s kids. “It’s been so cool to have a family that we never knew we would have,” muses Crystal. “It’s been a really fun surprise.”

In a corner of the dining room, a large vintage chalkboard purchased at a church yard sale and previously used in a Sunday school classroom sits on the wall. On the right side in black Sharpie, presumably written by a Sunday school student, it reads, “God is cool.”

Underneath the chalkboard, clearly not part of her aesthetic, is a box with items spilling out: her donation pile. “I am always gathering and purging, gathering and purging,” she says. While she frequents thrift stores as a shopper, she also replenishes them, happy to keep worthy items out of the landfill.

In fact, friends often inform her when they spy potentially good scores curbside, headed for the dump. One of her favorite finds, which came to her via a friend texting about “a pile of stuff at the curb” by their church, hangs on a wall in their guest room. “It’s a Burwood peacock, complete with its original crown,” says Crystal. “Out of the trash.”

Jason was flabbergasted to discover similar pieces sell for a couple hundred dollars. “And it was just sitting on the side of the road,” he says, shaking his head.

The fireplace in the same room has been painted a soft pink, though Crystal admits trying black first. “I hate black,” she says, adding, “It just doesn’t feel like me.” Above the, wait for it, pink mantel hangs a gilded vintage mirror, a gift from Karissa, who she is now able to spend time with regularly. “She’s a thrifter as well, so we’re always collecting.”

On the built-ins next to the guest room fireplace, rainbow-ordered books hand-selected by Crystal for their color line the shelves, purchased from her one of her favorite thrift stores, Blessingdale’s, a Southwest Greensboro gold mine for deal hunters. “They have books at eight-for-a-dollar!” she exclaims.

While she has filled her home with found treasures, the real gem of the house, according to Crystal, is the sunroom and the backyard.

Outside, several sculptural Moderne Russell Woodard chairs — Crystal’s most prized possessions — surround an aqua outdoor dining table snagged on Facebook marketplace. A pair of matching Woodard chaises with a side table sit just off to the side. “We actually unloaded our leather sofa at the farm because everything wasn’t going to fit,” she says. And she was not about to leave Russell Woodard behind.

The sunroom — also a shade of pink, Sherwin-Williams’ Malted Milk — serves as the family’s breakfast nook and homework hub. Flanking the room’s many windows are 1960s floral panels in shades of — you guessed it — blues, pinks and reds. “All my curtains came from Blessingdales,” says Crystal, who has hung vintage floral curtains in many-a-room.

Jason calls attention to the sturdy, large-scaled vintage classroom chairs, mustard yellow in color and serving as a clean-lined foil to the pastels and florals. “They are perfect for our boys — big boys,” quips Crystal, whose children take after their father.

Adjacent to the sunroom is the space that they’ve made the most changes to, the kitchen. With Jason’s help, Crystal, who has built quite a following on social media because of her keen eye for thrifty and colorful design, participated in a spring 2020 online event entitled “One Room Challenge,” sharing updates each week on her instagram page: @casa_carlisle. The couple removed cabinets from one wall, replacing them with open shelving, painted the lower cabinets and island in a custom shade of teal, painted the uppers white, replaced lighting with more modern fixtures, added wallpaper backsplashes and made it their own with personal details and thrifted touches.

But Jason knows his wife well enough to say, “I am pretty sure at this point she wants to paint these cabinets again.”

With a coy smile, she responds, “I’ve thought about it.”

“There’s nothing off the table,” says Jason, constantly in awe of the changes Crystal makes in their home “because it keeps the house fresh, keeps it new, keeps it different.”

These days, Crystal works full-time as an account executive for a furniture company in High Point and, while she still loves to fluff her nest, she doesn’t see many drastic changes on the horizon. “There are a couple projects I would like to tackle, but we’re right now at the point in our lives where weekends are for sports or for family stuff,” she says. “We just raised fun kids, so I want to hang out with them. We’ve raised our own little best friends.”

Later this month, the Carlisles will gather around their extra-long dining table with their boys, Karissa’s family, Uncle Earl and extended family from afar to give thanks for the most treasured North Carolina find: time spent with family and a house that has exceeded Crystal’s dreams — at least for now. OH

The first frost is nigh. Daylight saving time ends on Nov. 5. Autumn is edging toward winter.

The first frost is nigh. Daylight saving time ends on Nov. 5. Autumn is edging toward winter.