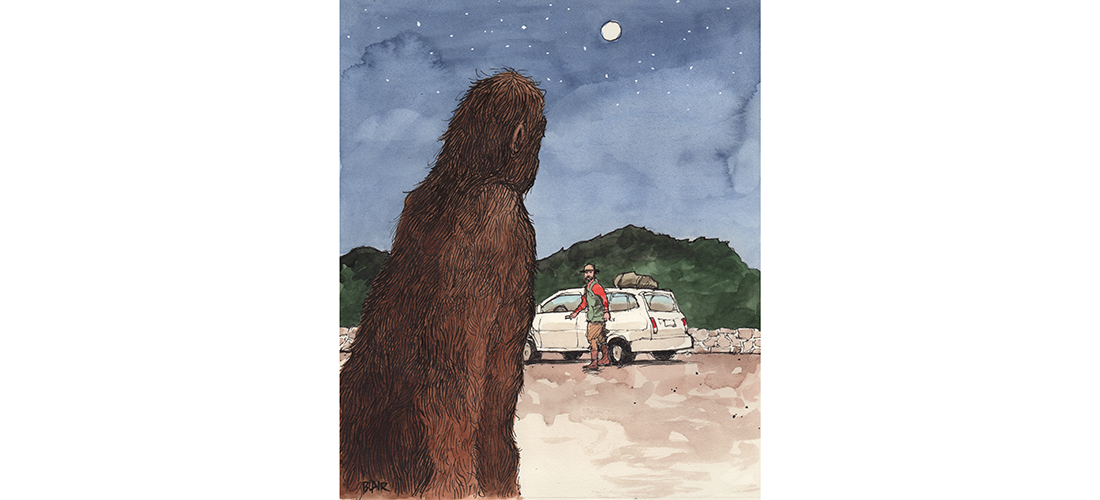

Here Be Monsters — In Carolina

Tall tales of the tall. tailed and terrifying

By John Hood

Illustrations by Harry Blair

It happened on the Blue Ridge Parkway.

Just west of Maggie Valley, the parkway intersects with Heintooga Ridge Road. To the south is the legendary Soco Gap. To the west is the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. And just up the road to the north, at the boundary of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is a striking monument made of stones from all over the world.

This stretch of the parkway is one of North Carolina’s most beautiful spots. One dark and foggy May night, however, Ashley Coleman saw something terrifying there. “The hairs on my arm and back of my neck stood up straight,” he says. “I have never in my life been so afraid.”

Coleman had parked at a nearby overlook to watch the setting sun. After returning to his car through the billowing mist, he began backing up — only to stop short as a huge figure dashed across the road and entered the woods. “It was entirely too large to be a black bear,” Coleman insisted, “and definitely wasn’t an elk.”

What was it? Well, I obtained these quotes from the Bigfoot Field Researchers Organization (BFRO), a 27-year-old group that bills itself as “the only scientific research organization exploring the bigfoot/sasquatch mystery.” Coleman’s reported May 30, 2021, sighting on the Blue Ridge Parkway has an official incident number (No. 69269) and designation (Class B, meaning “incidents where a possible sasquatch was observed at a great distance or in poor lighting conditions.”)

I begin with Coleman’s story in part because it’s our state’s most recent sighting. Many of North Carolina’s other BFRO cases are Class A, designating “clear sightings in circumstances where misinterpretation or misidentification of other animals can be ruled out with greater confidence.” In July 2020, for example, a Montgomery County motorist saw something bound across Highway 109. It was “large, maybe 8-feet,” she said, and covered in black fur except for lighter patches on its face and hands.

Every region of North Carolina is represented in the Bigfoot database. There’s the self-described “city boy” who went hunting near Elizabeth City and found not a deer but a furry, 8-foot-tall hominid munching on leaves.

There’s the vacationer returning to his Smithfield home and glimpsing “a bear walking upright with long legs and arms longer than a man’s.”

There’s the trucker who was headed up N.C. Highway 53 toward Jacksonville when a “very muscular” figure bolted onto the road. “It seemed to have no neck,” he reported, “just a head — sort of like a caveman.”

There’s the man in Archdale, just over the county line from High Point, who happened to peek through his front window and see a creature, also neckless and furry and 8-feet-tall, skulking around outside. After first comparing it to the ’70s cartoon character Captain Caveman, the homeowner reached back another decade for a suitable reference: “I guess it looked more like an overgrown cousin It from The Addams Family.”

And then there are the multiple sightings in Buncombe, Burke, and McDowell counties of mysterious hominids variously described as bear-like, smelling like “dead garbage” and swinging their arms “like pendulums.”

You have my permission to snort.

In olden times, cartographers would fill the unexplored corners of their maps with colorful illustrations of fantastic beasts and phrases such as “Here Be Lions” or “Here Be Monsters” or (on one 16th century globe) “Here Be Dragons.” But this is the 21st century. We’re supposed to be past this sort of thing. Plus, doesn’t everyone walk around with audio/video recorders in their pockets? Surely, we don’t need to place our trust in bleary-eyed motorists, excitable hunters and varied wanderers of the night talking of monsters ill-met by moonlight. If giant ape-men truly populated the marshes, forests and hills of the Old North State, surely, we’d have hard evidence by now.

I’ve always been a skeptical sort. Plus, I spent decades covering politicians. Need I say more? Lately, though, I’ve found my critical eye drawn away from genial true believers and toward what might be called performative skeptics. The kind who loudly, self-righteously denounce other people for chasing after Bigfoot and the like — and then, with a self-satisfied grin, glance down at their smart phones to check their horoscopes, buy healing crystals, watch New Age videos on TikTok or retweet their political tribe’s latest wild-eyed conspiracy theories.

When it comes to Bigfoot, the Loch Ness monster and many other cryptids — a modern coinage derived from cryptozoology, referring to creatures known from legend or rumor but never proven to exist — the imaginative leap to belief is arguably smaller than for, say, homeopathy or ESP. After all, while the prospect is highly unlikely, it would break no fundamental law of nature for some kind of “missing link” anthropoid to persist in the wild or for some supposedly extinct reptile to lurk in a deep body of water.

You need not be a true believer to find cryptids intriguing. Just ask Joneric Bruner. He’s from the aforementioned McDowell County and one of the organizers of the WNC Bigfoot Festival in Marion, the largest event of its kind in the eastern United States. Bruner estimates some 20,000 people attended the 2022 festival. Do they all treat the existence of Bigfoot as fact? Of course not. Many just came looking for a fun weekend — and found it, by all accounts.

You know who else doesn’t believe in Bigfoot? Bruner himself. “I’m open to the idea,” he told me, “but I’m not going to conclusively say, ‘Yes, he is real.’”

Like Bruner, I’m no true believer. I’m just curious, and in the market for story ideas.

After authoring many serious history books, I decided a couple of years ago to make a turn toward speculative fiction. My Folklore Cycle series of historical-fantasy stories began with the 2021 novel Mountain Folk, continuing with a novella (The Bard: A Mountain Folk Tale) and a second novel (Forest Folk, just published). In my fictional world, fairies and monsters coexist with historical figures such as George Washington, Daniel Boone and Sojourner Truth. It’s an improbable blend, I admit, but readers seem to enjoy it. What they especially appreciate, they tell me, is that few of my fantastic elements are fabricated from whole cloth. Rather, my research took me deep into European, African and Native American folklore, from which I imported magical creatures to my otherwise-realistic depiction of early America.

Much of the action is set in North Carolina, allowing me to draw from centuries-old traditions of monster lore. Here are four Carolina cryptids that make an appearance in the Folklore Cycle. Each represents a different region and cultural origin, yet all share a gruesome trait: drinking blood!

• The Whipping Snake: Stories of lightning-fast snakes that whip their prey into unconsciousness, then sink their fangs into an exposed vein, can be found throughout the Southern United States and Northern Mexico. But one of the first written accounts dates to Revolutionary War-era North Carolina. British General Henry Clinton sailed south from Boston in early 1776 to invade the Southern colonies. Reaching Wilmington in March, he expected to meet up with reinforcements, but they weren’t there. What did lay in wait at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, Clinton later wrote, was a dangerous beast, the Whipping Snake, that “meets you in the road and lashes you most unmercifully.”

• The Gallinipper: Several decades later, and further up the Cape Fear near modern-day Fayetteville and Dunn, the legend of the Gallinipper arose among workers harvesting timber and making tar, pitch and turpentine. They spoke of a giant mosquito, as big as a hawk, that could rise from a swamp or swoop down from a tree to attack. The Gallinipper probably reflects a blending of African and Native American lore. The Tuscarora, for example, told tales of a giant mosquito that “flew about with vast wings, making a loud noise, with a long stinger, and on whomsoever it lighted, it sucked out all the blood and killed him.”

• The Tlanusi: The Valley River runs southwest through the mountains to join the Hiwassee River in Murphy. Near the confluence is a place the Cherokee called Tlanusi’yi, “Place of the Leech.” The red-and-white-striped monster in question, the Tlanusi, was said to be as large as a house. It hid in an underwater cavern near a natural bridge of slippery rock. When someone tried to cross, the Giant Leech would break the surface, shoot a waterspout to knock the foolish traveler into the water and drag its prey below to feed.

• The Monster Cat: Tales of dangerous felines span many generations and regions. In the 19th century, the residents of Salisbury, Statesville, and other Piedmont communities spoke of encounters with the Santer, an enormous beast with glowing fur, long fangs, and a strong tail that, like the Whipping Snake, could be used to soften up its prey before going in for the bloody kill. Further north and west, mountain folk spoke of the Wampus Cat, variously described as having more than four legs, capable of walking upright on two legs or shapeshifting into human form.

North Carolina’s most-famous cat tale comes from the Sandhills. On December 29, 1953, a resident of the Bladen County town of Clarkton reported seeing an impossibly large cat on the prowl. Two days later, a local farmer reported two dead dogs. Their bodies were mangled and drained entirely of blood. Other attacks followed. On January 5, a Mrs. Kinlaw rushed outside to comfort her whimpering dogs. Something like “a big mountain lion” sprung at her, Mrs. Kinlaw later said, before retreating down a dirt road. “‘Vampire’ Charges Woman,” screamed the resulting headline in the Raleigh News & Observer. The so-called Beast of Bladenboro was never seen again — well, except on the cover of my novel, Mountain Folk.

✣

Now, perhaps, you can guess the real reason I led off with that May 2021 report of Bigfoot on the Blue Ridge Parkway. For starters, the incident occurred just east of the Cherokee reservation, and native folklore plays an outsized role in North Carolina’s tradition of monster tales. To the south lies Soco Gap, where legend has it that local hero Junaluska confronted the famous Tecumseh and insisted he not try to bring the Cherokee into his Confederacy. Junaluska has many adventures in the pages of my new novel, Forest Folk, including a desperate battle with a Giant Leech. And, as I mentioned, just north of the purported Bigfoot crossing is a monument made from stones painstakingly assembled from many different places. From the Carolina mountains and foothills, yes, but also from the White House, the Alamo, even the Rock of Gibraltar. As it happens, all these places are featured in published or forthcoming books in my Folklore Cycle.

What does that stone monument honor? Freemasonry!

History, heroes, picturesque locales, fantastic beasts, the Masonic fount of a thousand conspiracy theories — it sure has the makings of a great story. And a great story is what countless generations wanted to hear. It’s what the crowds of people flocking to Bigfoot festivals still want to hear. They want to live in a world where not all questions have been answered, where not all mysteries have been solved, where something furry, slimy, or improbably gargantuan may yet be lurking in the darkest corners of their mental map.

I want to live in that world, too. Don’t you? OH

John Hood is a Raleigh-based writer. The latest book in his Folklore Cycle series of historical-fantasy tales, Forest Folk, was published in April.