Thinking Outside the Box

Beware of fraud — but not too much

By Maria Johnson

The package on our doorstep was large, maybe 2 feet by 2 feet.

Too big for the paper bathroom cups I’d ordered. Way too big for the wooden floor vent due to arrive any day.

“Did you order anything this big?” I asked my husband.

He shook his head.

I checked the label.

It was addressed to me.

I looked at the return address. The sender was something called Muji in New Jersey.

“MOO-gee?” I said slowly. “What’s a MOO-gee?”

I looked at my husband.

“Emoji?” he said.

“Not emoji. A MOO-GEE,” I said, acting as if the words sounded nothing alike.

I proceeded with caution, grabbing a pair of scissors, carefully slitting the packing tape and slowly opening the cardboard flaps.

You never know what a Muji from Jersey might send. A packing slip lay atop some crumpled brown paper.

I unfolded the slip to see a manifest of the contents:

“Item.”

“Item.”

“Item.”

No prices were given.

Okaaaaaaay.

I set aside the slip and lifted a layer of the packing paper to reveal a clear plastic storage box with a lid.

In-ter-est-ing.

Under that, another layer of paper.

I gingerly lifted the wads.

Two stackable plastic trays. Or, as we used to say back in the day, an in-box and an out-box.

How quaint.

And weird.

I picked up the packing slip again. It gave no website for Muji. No phone number.

Just a fuzzy QR code.

“Maybe you should scan the code,” my husband suggested.

Hmph. I’d read way too many scam stories, received too many “urgent” text alerts about nonexistent bank accounts and listened to too many voicemails regarding my request for a business loan — huh? — to fall for this.

And yet, a part of me would feel guilty about keeping these plastic accessories I had not paid for.

Equally bad, I imagined someone out there, sitting at a desk strewn with the disorganized chapters of the next Great American Novel, just waiting for a 2-by-2 box that never arrived.

Danged human emotions. Danged scammers for preying on them.

Why, just the week before, I’d received two cunning, if clumsy, emails that I found myself reading and responding to in my head.

One was an email from my long lost friend Jimmy at PayPal, as proven by the fuzzy company logo below his message. Never mind Jimmy’s personal Gmail address.

“Hi,” he wrote. “I hope you’re doing well and reading this message.” (Yes to both, Jimmy, though who can say how long either will last?)

“We haven’t caught up in much too long.” (Like, ever.)

“I’ve been missing our amazing connection and our discussions.” (We’re talking about PayPal, right? But, yeah, it’s true. I’m a good listener.)

“I wanted to get in touch with you and start off again.” (I do like a good repair attempt.)

“We can communicate via email, video call or in-person meeting . . . ” (In person? To talk about my PayPal account? I dunno . . . This seems . . . Well . . . Maybe over coffee?)

“Till we cross paths again, be well and never forget that you are missed.” (Do you really expect me to have coffee with a man who uses the word “till” in a business letter? It’s over, Jimmy.)

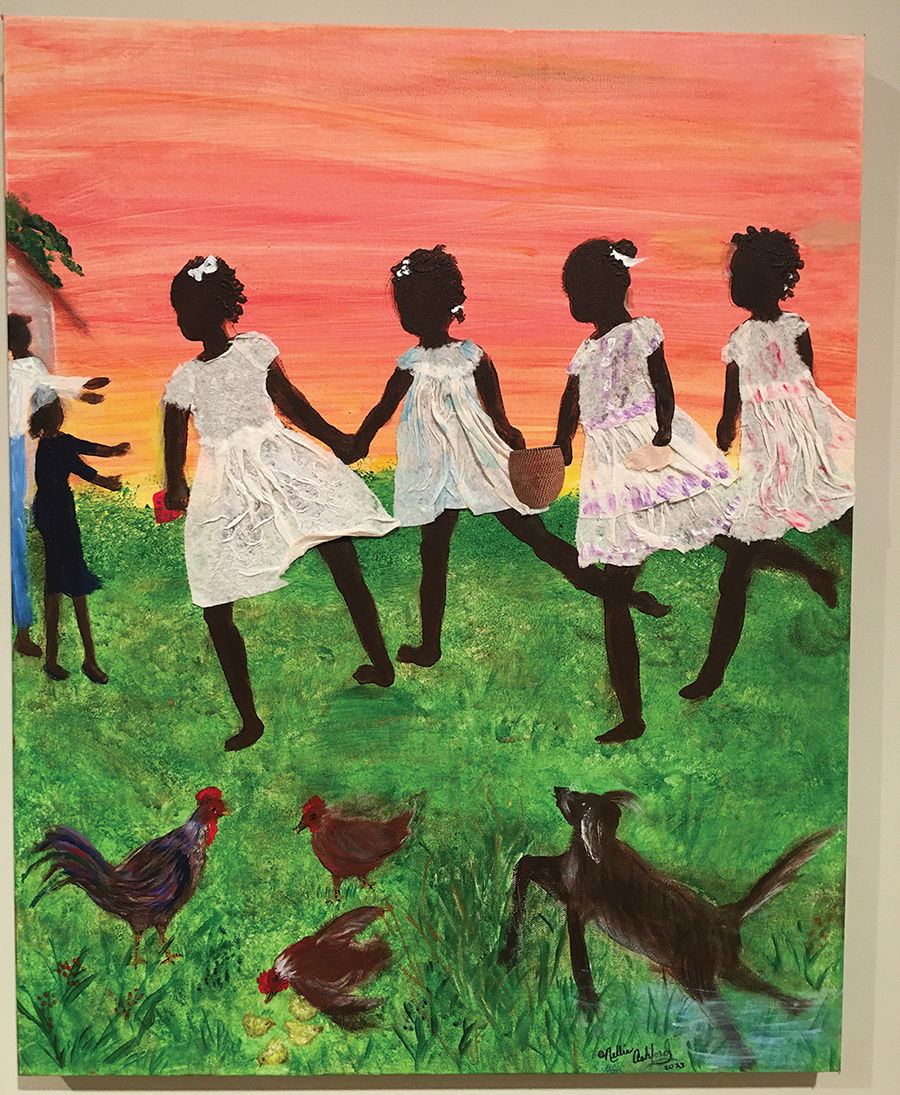

Then there was this flattering note with “ART INQUIRY” in the subject line.

“How are you doing? My name is Paul Arthur from Atlanta, GA.” (That’s a lot to cram on a birth certificate, Paul Arthur of Atlanta, GA.)

“I have been on the lookout for some artworks lately in regards to I and my wife’s anniversary which is just around the corner. I must admit your doing quite an impressive job.” (Artworks? You must be talking about the flower pots that I’ve been encrusting with orphaned earrings, a sort of hot-glued reminder of lobes past. I saw it on Etsy. They’re cute, aren’t they? And you are obviously a man of taste. Though your spelling and grammar need work. It’s “you’re,” not “your,” and technically you should have said, “my wife’s and my anniversary.” Or even better, “I’ve been looking for some artwork to buy my wife for our anniversary.” Much simpler.)

“You are undoubtedly good at what you do.” (Paul. You charming devil.)

“I would like to purchase some of your works as a surprise gift to my wife in hoding anniversary.” (Hoding?)

“My budget for this is within the price range of $500 to $5,000 dollars.” (H-O-D-I-N-G?)

“I look forward to reading from you in a view to knowing more about your pieces of inventory.” (Do you mean the paper anniversary? Or the cotton anniversary? Or maybe the pottery anniversary?)

The point is, it’s easy to get sucked into these things even when you know they’re fakes.

I stared at the Muji box. I wasn’t about to scan the splotchy QR code and potentially open the door for a malicious actor to commandeer my device and do God-knows-what with my dog pictures.

I double checked my outstanding internet orders. Had I ordered desk accessories in my sleep? Was this a sign from my subconscious that I needed to literally get my stuff together?

Zippo.

I was stuck. Finally, my husband offered an idea: “Just throw it out.”

What? Throw away a perfectly good plastic storage bin and two filing trays that probably cost 10 cents to manufacture?

No way. I would recycle them. No, wait, even better, I would donate them, take a small tax write-off and keep alive the chance that the person who’d ordered these things would find them at Goodwill.

That would solve it. Clean conscience all around.

I put the box by the door. The next time I left the house, this puppy was going in my trunk.

About 30 minutes later, our son in New York texted.

“I may have accidentally had a Muji package sent to you rather than here. If it shows up, would you be able to forward it to us? No rush.”

I did what any loving mother would do.

I asked him a security question. OH

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry magazine. Email her at ohenrymaria@gmail.com.