O.Henry Ending

O.HENRY ENDING

Food, Actually

If you look for it, I’ve got a sneaky feeling you’ll find that love actually is all around the table

By David Claude Bailey

This is a love story. It began 60 years ago.

Our new Boy Scout executive, Wofford Malphrus, is explaining how we’ll have more guns, more bows and arrows, more everything at summer camp. As he’s leaving, he pulls a photo from his wallet and says, “This is my daughter and some of you will be going to school with her next year.”

I am stunned. She is without doubt the most beautiful woman on the planet. At the same moment, I realize I have zero chances of ever dating her. In fact, at age 15 — shy, one-eyed, gawky, a beatnik wanna-be — I’m yet to have my first date.

Fast-forward two years and my best friend, Spencer, tells me that Anne Malphrus has seen my ’45 Ford army surplus heap of a Jeep and wants to ride in it.

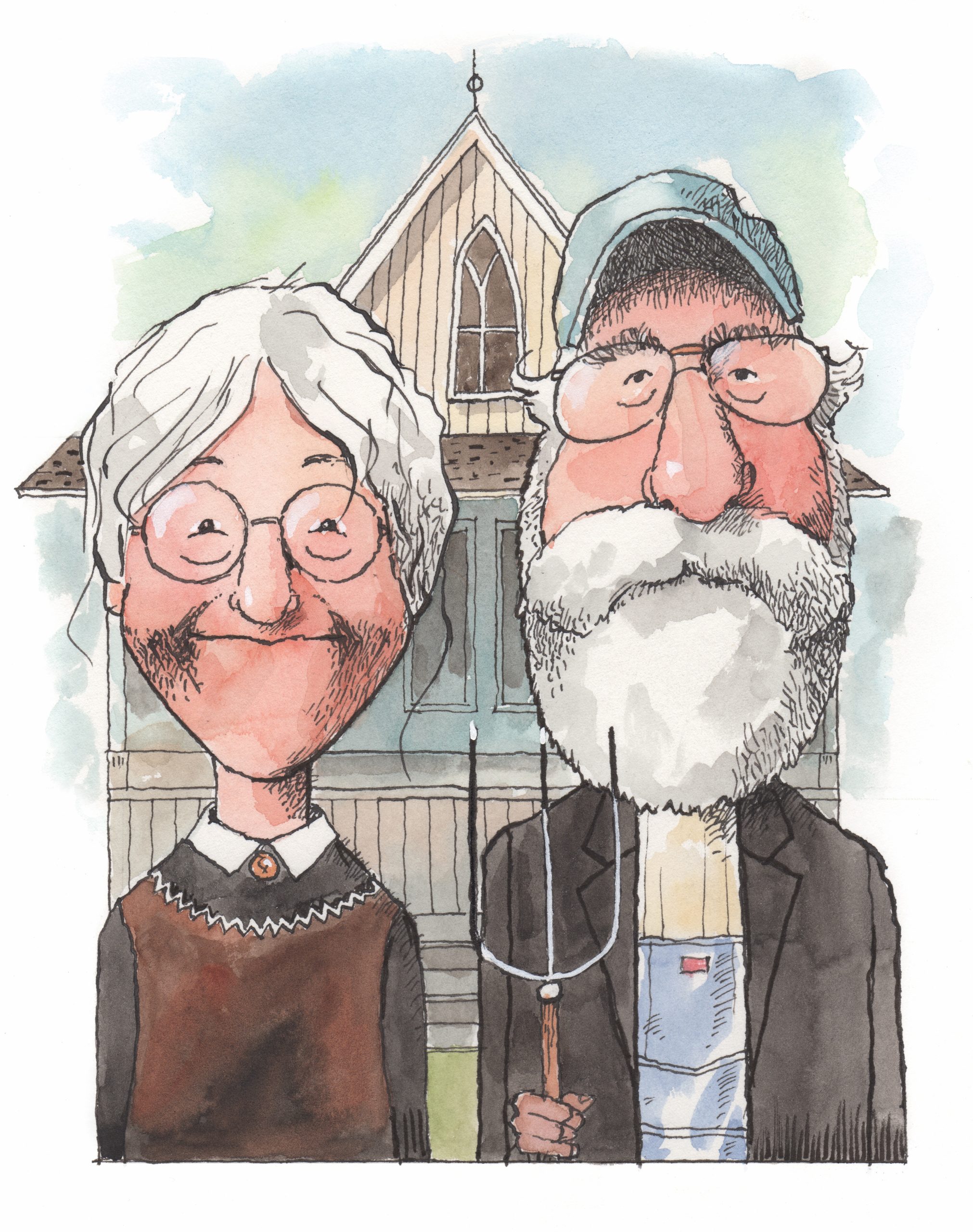

And she does. Double dating with my cousin, Bill, and Anne’s best friend, Mary, we picnic at my uncle’s farm. My mother packs leftover roast duck and blue cheese, while Bill’s mom sends deviled eggs and savory lemon bars. It’s love at first bite as two foodies feast away. In sprinkling rain on the way back to the car, our first kiss comes as we huddle under the picnic blanket.

We remain an item through Anne’s freshman year at UNCG, when we elope and get married under our Greek professor’s whispering pines. A year later, we take a sabbatical from school and hitchhike all over Europe, mostly in Spain and Greece where we can afford to stay in a hotel instead of a youth hostel. We discover heady gazpacho, goat cheese and succulent melon served with paper-thin slices of Iberian ham. Hello, rabo de toro (bull’s tail stew), calamari and bacalao (salt cod with tomato sauce).

Time passes and we’re still together — me, a reporter covering the earliest days of the Space Shuttle; Anne, an artist and food columnist. On our 13th anniversary, Anne tells me no more excuses, no more delays, it’s time to have a child.

We do, first Sarah and then Alice. And so begins the most magical years of our lives, reliving youth through our children’s eyes, building villages out of twigs and rocks for Terabithians, reading them the same fairy tales our mothers read us. Our girls learn to ride bikes, swim, make and keep friends, drive cars. We blink and they’re off to college.

A few years later, Sarah announces she’s moving to Spain. She does and loves it. Over the next 20 years, she manages to acquire a husband, a horse and an apartment in Europe’s equivalent to Myrtle Beach, Mallorca. Gaining Spanish residency, she works in a digital job we barely understand. A cordial divorce follows.

She moves to Málaga and falls for Toni Mayo, a landscape designer, serial entrepreneur and Airbnb owner. After spending Christmas with his family in La Higuera, way up in the mountains, she becomes part of a loving Spanish family, who adopt her without reservation.

Finally, at age 43, Sarah figures out how to have children and presents us with a perfect grandchild, Jeva.

It’s Christmas Eve. As a fire crackles in the hearth, Toni’s mother’s house fills with Jeva’s aunts, uncles, her great grandmother and the world’s dumbest Labrador. Anne and I are on the floor with Jeva, who is now, surprise, a bossy 2-year-old. She is sitting very contentedly in my lap as I read to her, for the 40th time this season, the adventures of Santa Bear. Soon, we sit down to shrimp croquettes, gazpachuelo (a rich fish soup creamy with mayonnaise), antequerano (cod with oranges) and an array of other traditional holiday dishes, washed down with sparkling Spanish cava. Standing up, I propose a toast to love and to family, a family that has adopted me and my loved ones — heart, soul and stomach.