Story of a House

A Wink From the Universe

For shop owner Kam Culler, it’s all about family and home

By Cassie Bustamante

Photographs by Amy Freeman

Growth charts on door frames and bright orange permanent marker doodles on the wall might not be popular Pinterest decor, but for Kam Culler, home is all about the memories she creates there with her family.

Pointing to a shimmering gold-and-aqua tassel garland hanging in a door, she says, “Those are from our housewarming party five years ago.” Culler pivots and shows off a colorful string of pom-poms. “Those are from Charlee’s 4th birthday. We did Kidchella.”

Culler, who was just 23 when she began fixing up her midcentury 1959 split-level ranch in Old Starmount Forest, is an independent go-getter. In the last few action-packed years, she’s married the love of her life, given birth to a second child and started her own business — all while rehabbing her home. “I’ve had a lot of help from my friends and family, and my late sister-in-law,” she says. “But I want people to see a woman can do it all.”

When she first looked at homes as a single mom to then toddler Charlee in 2017, something about this house spoke to her. While Culler loves homes of that era for the charm and character they offer, this ranch style specifically symbolized to her “America’s frontier spirit and a new age and new growth of a new culture.”

Feeding not only her cosmic spirit, the house offered a little wink from the universe, a nod to let her know this was the one. The previous owners had created a poker room off of the garage that most people would want to change immediately. But the space held special meaning to her. Holding up her forearm, she cheerfully points out, “My grandfather and I play poker. My tattoo that says ‘lucky’ is for him.”

In the kitchen, the previous owners had repurposed some old plates their children had broken into a mosaic backsplash. While it wasn’t Culler’s style, she thought, “Alright, this is definitely a house for a kid.”

After seeing a multitude of houses, Culler, just 23-years-old at the time, trusted her instincts and made the decision to purchase the ranch, envisioning a future for herself and Charlee. Knowing that the house needed some work and updating, she was ready to commit because “it just felt homey.”

Shortly after moving in, an old magnolia on the property fell on the back of the house, setting a series of renovations into motion. The room that would become the playroom, for instance, flooded and required a complete overhaul, as did the upstairs bathroom off of her main bedroom.

While she hadn’t planned to update so soon, Culler hired Savas Construction to create a whimsical and feminine play space for daughter Charlee (and Wrennlee, who just joined the family in July). The room now features walls that are white on top and a soft pink on the bottom, paired with Kam’s signature colorful and cozy textiles found throughout her home. In the corner, Charlee can safely write on the wall on a wood-framed, house-shaped chalkboard.

In her own bathroom, Culler repurposed a vintage dresser, its aqua paint adding a vibrant splash of color against the black-and-white ceramic floor tile and modern white shiplap walls. Photos of a smiling Culler and Charlee taken throughout the years at Anthropologie’s mother-daughter fashion shows and dance recitals adorn the walls.

But the pièce de resistance, according to her, is the large, white basin-style bathtub. “That was the one thing,” quips Culler, who’s 6-feet tall. “I was like, ‘If we’re going to redo this, I want a bathtub that can fit my boobs and knees in’ — achieved!”

Construction was already underway on the playroom and bathroom when Culler decided to have her kitchen countertops replaced. But, “funny story again,” it turned out not to be as simple as that. Shelving and cabinetry were removed from the walls for measuring, revealing that the walls beneath were not lined with drywall.

While she hadn’t planned to update so soon, Culler hired Savas Construction to create a whimsical and feminine play space for daughter Charlee (and Wrennlee, who just joined the family in July). The room now features walls that are white on top and a soft pink on the bottom, paired with Kam’s signature colorful and cozy textiles found throughout her home. In the corner, Charlee can safely write on the wall on a wood-framed, house-shaped chalkboard.

In her own bathroom, Culler repurposed a vintage dresser, its aqua paint adding a vibrant splash of color against the black-and-white ceramic floor tile and modern white shiplap walls. Photos of a smiling Culler and Charlee taken throughout the years at Anthropologie’s mother-daughter fashion shows and dance recitals adorn the walls.

But the pièce de resistance, according to her, is the large, white basin-style bathtub. “That was the one thing,” quips Culler, who’s 6-feet tall. “I was like, ‘If we’re going to redo this, I want a bathtub that can fit my boobs and knees in’ — achieved!”

Construction was already underway on the playroom and bathroom when Culler decided to have her kitchen countertops replaced. But, “funny story again,” it turned out not to be as simple as that. Shelving and cabinetry were removed from the walls for measuring, revealing that the walls beneath were not lined with drywall.

“It was brick, wood, and the cabinets were literally superglued, so there was no saving them.”

Today, the galley kitchen features modern dark green-gray cabinets with black cup pulls, a charcoal-grouted white subway tile backsplash, smooth white quartz countertops, white Café appliances with copper accents and open shelving consisting of 2-inch walnut slabs. It is as striking as it is functional.

Of course, it’s not shelves that make the kitchen for Culler, but what’s on them. Over the years, Charlee has spent many birthdays at Mad Splatter, creating something new to commemorate each family milestone. While plants and everyday dishes occupy much of the shelves’ real estate, Charlee’s works of art hold the esteemed position on the top shelf.

Recently, Culler rearranged the open shelving to accommodate the color-blindness of her newest family member, her husband Kyle. He came into her life in the middle of 2020 when he pulled into her driveway, “delivering plants — imagine that!” Looking around Culler’s lush house, it’s not hard to imagine at all.

When the COVID pandemic struck in March of 2020, Culler was a 26-year-old single mom. Now she’s a married mother of two girls, Charlee and newborn Wrennlee.

The couple married at Cadillac Service Garage in a bohemian-inspired setting designed by Culler in October 2021. Two weeks later, she signed the lease on what would become The Borough Market & Bar. Just one month later, she discovered she was pregnant again.

Kyle didn’t bring much baggage, just several journals from years of service as a missionary. “He’s lived in a thousand places,” Culler points out, adding that all of those years of living minimally have served him well in his transition into this house. He has one wardrobe in the bedroom to himself and a small collection of what Culler calls “tiny little man hats,” as compared to her own wide-brimmed assortment.

She wasn’t about to let the busy-ness of life alter her dreams to have a shop of her own. “Yes, I’m a mom and then I do this,” she adds, referring to owning her business. As a mother to two girls, Culler wants to illustrate that anything is possible when a woman leans into her dreams and leans on her people.

The Borough Market & Bar was created to cultivate a stronger sense of community and would not be possible without her own supportive community. “I would not be where I am without my family,” muses Culler.

Sadly, her 23-year-old sister-in-law, Caroline, passed away in May. She was also pregnant with a girl and due shortly after Culler, who had made the decision to hire her because “we knew, or thought, she was here to stay.” Caroline had been at The Borough from the beginning, opening boxes and putting out merchandise. “I had a lot of help from her,” Culler sighs, tears forming in her eyes.

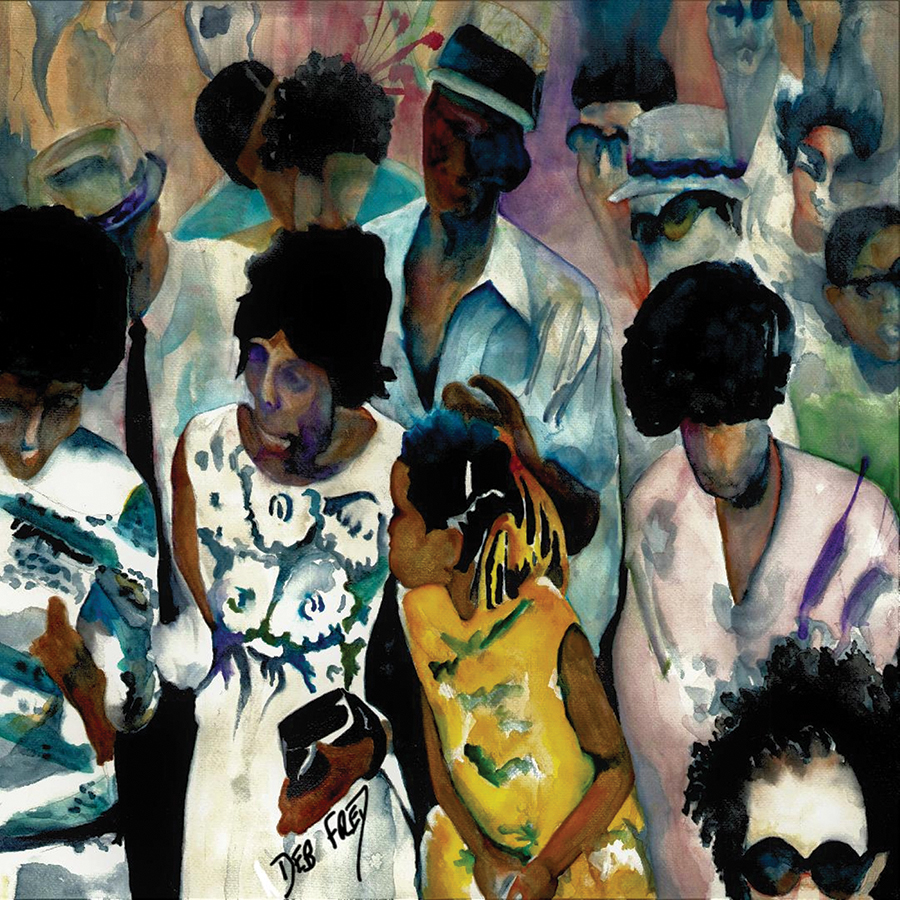

A dresser in Culler’s living room, the space where she spends most of her time, holds a treasured illustration of the two young women that a friend gave her for her birthday shortly after Caroline’s passing.

Culler’s grandfather, Jerry Hardy, has also played an integral part in the creation of The Borough Market & Bar. “He’s my person,” declares Culler. “Pop is who really helped the vision come to life after COVID.”

That vision is centered on a sense of home and community. Culler was inspired by a visit to London’s Borough Market as an Elon undergrad, studying abroad, appreciating its communal vibes. Armed with over 10 years of working in retail for Urban Outfitters, Anthropologie and Lululemon, she was able to make the dream a reality.

Her own Battleground Avenue establishment is divided into two spaces: a lounge and bar area that invites customers to relax over a cup of coffee or signature cocktail, and a boutique filled with eclectic goods from female-owned small businesses.

After a long period of many people using their kitchens as home offices, Culler wanted to offer a relaxed alternative. “They get to have their sacred space of home back, but go somewhere pretty and inspiring to work.”

The bar specializes in bourbon beverages, which is no accident since it’s Culler’s preferred spirit, a true reflection of who she is — a woman who honors her family’s past.

“Bourbon is like the story of my life. The longer it’s aged, the more craftsmanship goes into it,” she says. “It tastes better. It can open up your senses.”

This fall, she will partner with several neighborhood businesses to offer “Whiskey Around the World” pairing dinners at The Borough Market & Bar.

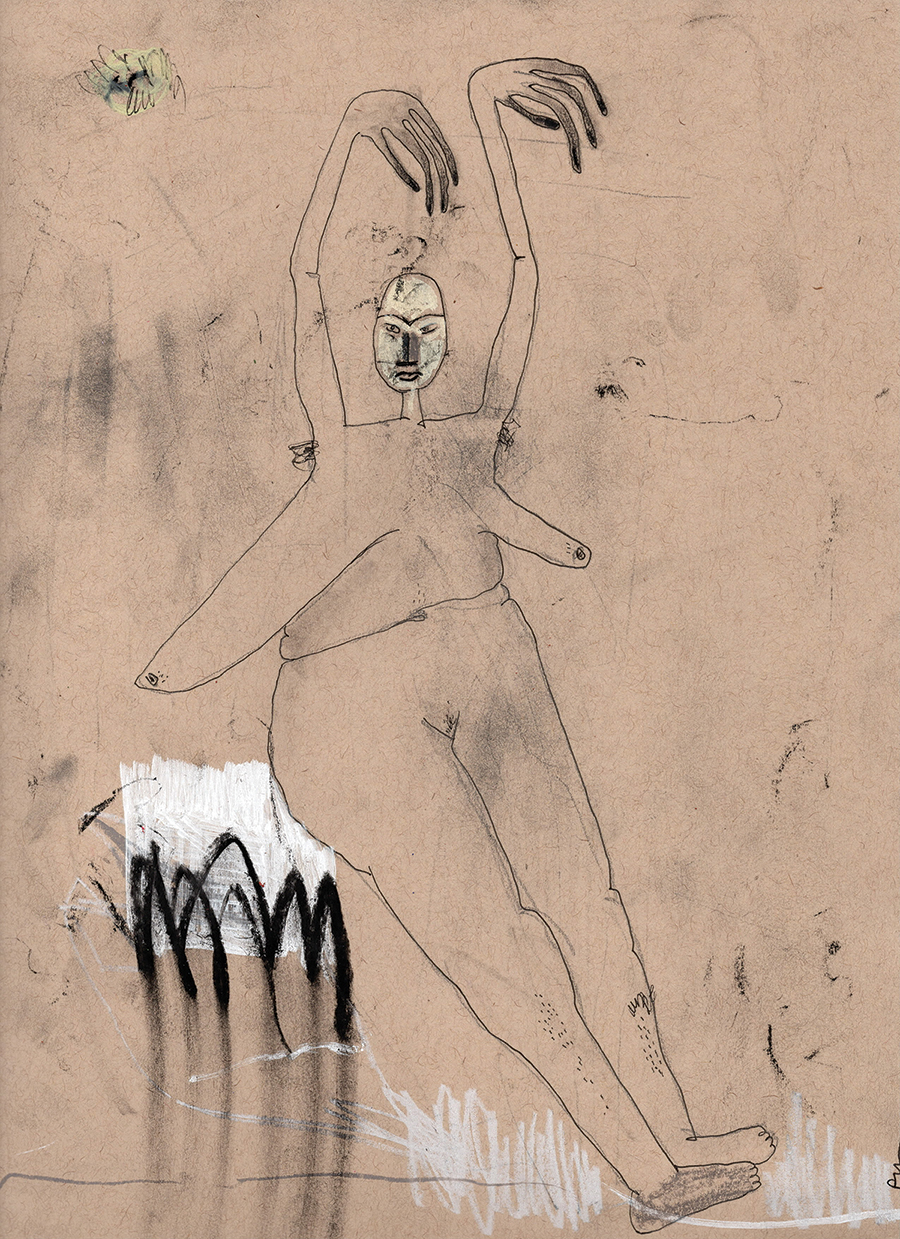

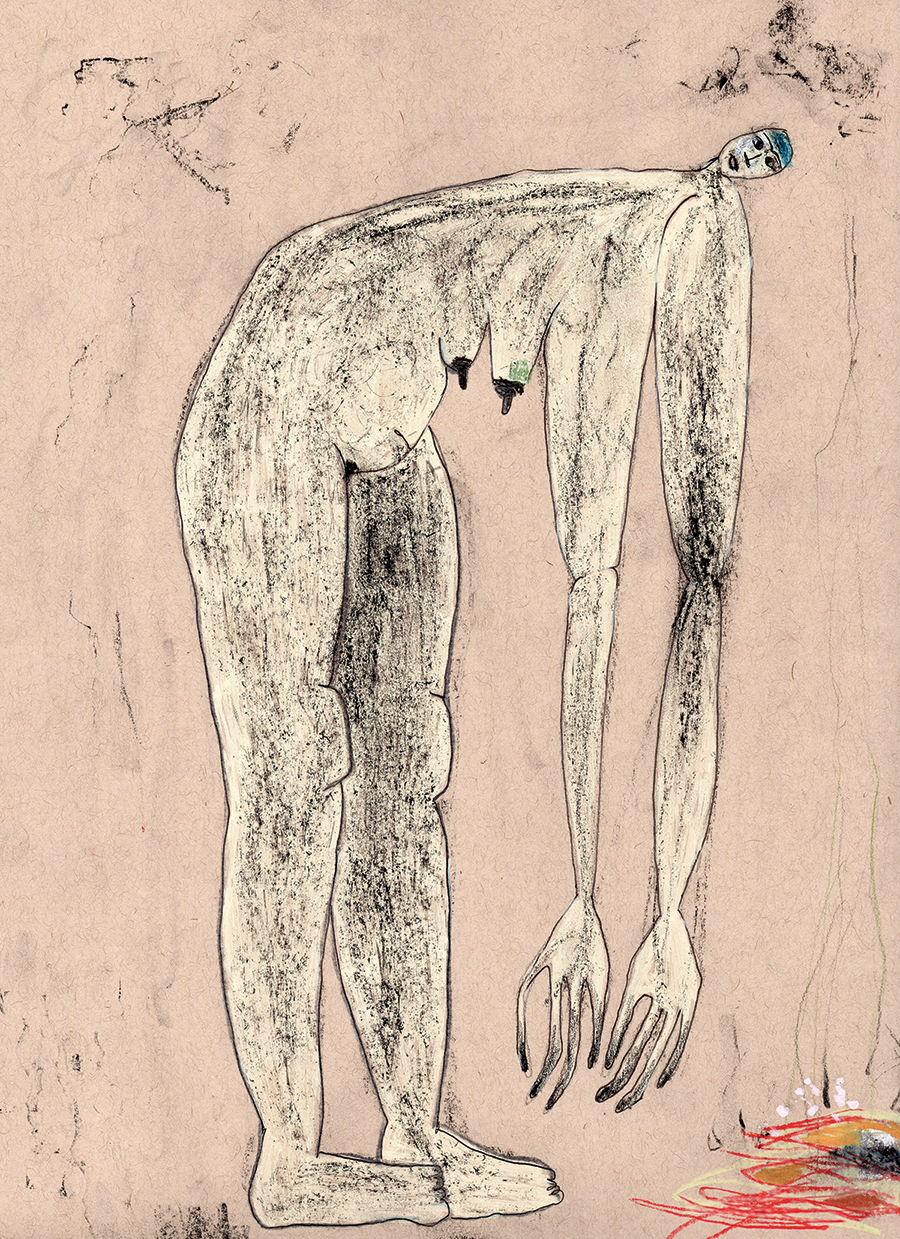

Her boutique is a commercial tribute to Greensboro creatives, featuring murals from local artists, Marley Soden and Jenna Rice, plus large paintings from Angie the Rose. The boutique also includes smaller pieces of art from Thea DeLoreto and Amber Taylor Creative, plus plants from Tiny Plant Market.

Looking for a sense of quality and heritage, Culler curates products for the shop just as she would for her home. She loves pieces she knows can be passed down through generations, much like the sideboard that once belonged to her grandparents.

“Smell and light sensory is a big thing with me,” Culler explains, pointing out why her home sanctuary is a space filled with twinkling lights, earthy hues of rust and pink, luscious green plants, family mementos, stray toys and nubby pillows, sofa and rugs. It’s here that she decompresses with a hot cup of coffee and her prayer journal after a long day down on Battleground Avenue.

Glancing around her transformed living room, she muses, “I really wanted to be that hippie, herb mom, but I’m probably more like Amazon, Target and Starbucks.”

However one chooses to describe her, like her home and business, Culler is an American original — an independent woman with a style all her own.

Pausing to reflect on the full life she and Kyle have embarked on, Culler sees their Starmount Forest ranch filled with “princesses and fairies, dance recitals and gymnastics, leotards and make up and sparkles and hair.” Even Kyle, who’s bald, gets in on the action, studying YouTube videos on braiding so that he can be “the ultimate girl dad.”

As if on cue, Charlee materializes in the hallway, dressed head-to-toe in her latest dance recital costume, a lavender top with sequins and tulle ruffles paired with shiny teal lamé tights that emulate the look of Disney’s Little Mermaid. In this sparkling and magical moment, it’s easy to see that in this house, dreams are not only created, but brought to life. OH

Cassie Bustamante is the managing editor of O.Henry magazine and a frequent shopper of Greensboro establishments — especially when there’s a coffee bar inside.