HOT DOG!

Our intrepid reporter goes for a whirl in the Wienermobile

It was the perfect evening for a winter festival.

The air was pleasantly chilly — or perhaps I should say chili — and spiked with the smell of fried dough and the bump of live music.

Revelers lined up to try their luck aboard a mechanical, bucking Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer. In another particularly American display of affection for the holiday, children in padded red suits and headgear tried to knock each other down in spirited rounds of Sumo Santa.

Yes, it really was shaping up to be an ideal Festival of Lights as my husband and I threaded our way down Greensboro’s Elm Street, when what to my wondering eyes should appear but curvilinear gleams of orange and yellow.

“Wait, is that . . . ?”

“What?”

“Oh, my God.”

“What?”

“It is!”

“What are you looking at?”

“It’s the Wienermobile!” I said, breaking into a trot.

I stopped in front of a bubble-shaped windshield, giddy at the fact that I was in the presence of an American icon.

I can’t say for sure when the Wienermobile first entered my consciousness. As a child of the ’60s and ’70s, I’m sure I saw it on TV, in holiday parades and Oscar Mayer commercials.

I have a vague memory of our family car passing a huge rolling wiener on Interstate 75, but I could be confusing that with a colorful tanker. Or it could be the result of wishful thinking and an excellent jingle.

Oh, I wish I were an Oscar Mayer wiener,

That is what I truly want to be—ee—ee,

‘Cause if I were an Oscar Mayer wiener,

Everyone would be in love with me.

Obviously, all these years later, seasoned by life’s experiences, I believe . . . that’s still true.

Everyone loves a hot dog, even a mostly plant-based foodie like myself. Wave a Carolina dog — slaw, chili, onions, extra mustard — in front of me, and I cannot be responsible for what happens next.

And now? There I was, standing next to the Wienermobile, all 27 feet of it, parked curbside with its gull-wing door lifted so that gawkers could marvel at the luxurious interior, which included six bucket seats upholstered in bright red and yellow, as well as a squiggle of yellow painted on the floor.

In Wienermobile culture, red equals ketchup. Yellow, mustard. That’s why the keepers of the wiener, two young dynamos named Keagan Schlosser and Chad Colgrove, were dressed in red and yellow pullovers. They invited the crowd to stick their heads inside the Wienermobile, pose for pictures and take home individually packaged, red plastic Wiener Whistles.

I asked Keagan if I could, for journalistic reasons, arrange for a ride in the Wienermobile during their stay. She said that would be “bun-derful.” Two days later — after the Festival of Lights and the Christmas parade — I climbed aboard for a Sunday morning spin.

Keagan asked where I wanted to go.

In a perfect world, we would have picked up my 90-year-old mom from church, the Wienermobile’s jingle-horn tootling just as the postlude faded.

My mom would have been slightly — OK, a lot — aghast, but also flattered. Ultimately, I thought, she’d cave to peer pressure from church pals who would want a ride, too.

As it turned out, my mom stayed at home with a mild illness that morning. Damn it.

My second choice was the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park because it, too, represented a significant piece of American history. Plus loads of people walk there on Sunday mornings. Off we went, as Keagan and Chad, both 23, shared how they became regional wiener drivers.

A native of Carbondale, Illinois, Keagan — who is no relation to the Greensboro Schlossers, sorry, guys — was about to graduate from the University of Wisconsin last spring with a degree in journalism. She’d interned at a local TV station. But the news biz was too serious, she felt, so she started looking into Hotdogger jobs, one-year gigs offered to recent college graduates by Madison-based Oscar Mayer.

Her journalism professors encouraged her to go for it. I repeat: Her journalism professors urged her to shun the Fourth Estate in order to pilot a giant fiberglass wiener around the country for a year.

I could not argue with their advice.

Chad, on the other hand, had known about the Wienermobile from the time he was a tyke in Boise, Idaho. Every year since he was 6, his family would sniff out nearby Wienermobile appearances and snap a picture of Chad grinning beside the seven-ton sausage.

As a teen, Chad rolled his eyes at this tradition, but his mom insisted, saying, “You never know. You might want to drive it one day.”

Naturally, Chad submitted all of those pictures with his job application, and he was chosen as one of 12 Hotdoggers from among 2,000 applicants.

“My mom literally started crying,” he said.

“I think my family was a little more confused,” said Keagan, explaining that they’d been pulling for graduate school, but they softened when she told them that it was harder to get into Hot Dog High than to be accepted at Harvard University.

Among the things Keagan and Chad learned in weenie school:

*The original Wienermobile was created in 1936, in Chicago, by Oscar Mayer’s nephew Carl. The open-cockpit novelty car gave out samples. After a fleet of Wienermobiles was deployed in 1988, they stopped dispensing free hot dogs.

*There are six Wienermobiles cruising America’s “hot dog highways,” stopping for gatherings such as car shows, sporting events, parades, festivals, as well as promotional appearances at stores that sell Oscar Mayer products. (Track the Wienermobiles at https://khcmobiletour.com/wienermobile)

*Built on GMC cab-forward truck chassis, Wienermobiles are powered by 8-cylinder gas engines. They get roughly the same gas mileage as a large SUV. The bodies are fabricated 40 miles from Greensboro at a Pfafftown company called Spevco Inc.

*Jay Leno drove the Wienermobile for a 2017 episode of Jay Leno’s Garage. Actor Tim Allen blew a Weiner Whistle in the 1994 movie, The Santa Clause. Bible-thumping Ned Flanders, of all people, drove the Wienermobile in a 2019 episode of The Simpsons. Inexplicably, Jerry Seinfeld has not asked to borrow the Wienermobile for Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee.

*The best place to wash a Wienermobile is a fire station. “We ask them if we can use their scrubby brushes and water to clean our wiener,” says Keagan. So far, they have not been refused. “Firemen love the Wienermobile,” she adds.

You could argue that a Harvard degree would better prepare a young person to serve the world than a hitch in the Wienermobile, but after tooling around the military park with Keagan and Chad, I’m not so sure.

You’ve never seen such immediate and whole-hearted smiles, followed by cell-phone fumbling and picture taking.

By the older guy in the San Francisco 49ers sweatshirt.

And the supercool driver of the Tesla stopped at the crosswalk.

And the young guy with the topknot. And the middle-aged couple walking two big white fill-in-the-blank-a-doodles.

And by 11-year-old Layla Jordan and her mom, Mojgan, who quickly waved her daughter into a photo beside the Wienermobile when we stopped at a light.

Keagan and Chad popped the hatch, jumped out and handed Layla a plastic Wiener Whistle.

“Your brother is going to be so jealous,” Mojgan said.

They handed mom another whistle and invited Layla to pose for a picture with them.

“Say ‘Cheeeeeeesy Wieeeeener!’” they coaxed.

Back inside the Wienermobile, Chad and Keagan mused about what would come next for them. Chad hopes to land a corporate wiener job with Oscar Mayer. Keagan, who has successfully driven the Wienermobile around Manhattan several times — and therefore feels, justifiably, that she can do anything — dreams of a big-city job with one of the marketing firms that contracts with Oscar Mayer.

“We’re relishing this while we can,” said Chad with a face as straight as a foot-long. OH

Applications are now open to become the next hotdogger. For more information, visit oscarmayer.com/wienermobile.

Maria Johnson is a contributing editor of O.Henry. Contact her at

ohenrymaria@gmail.com.

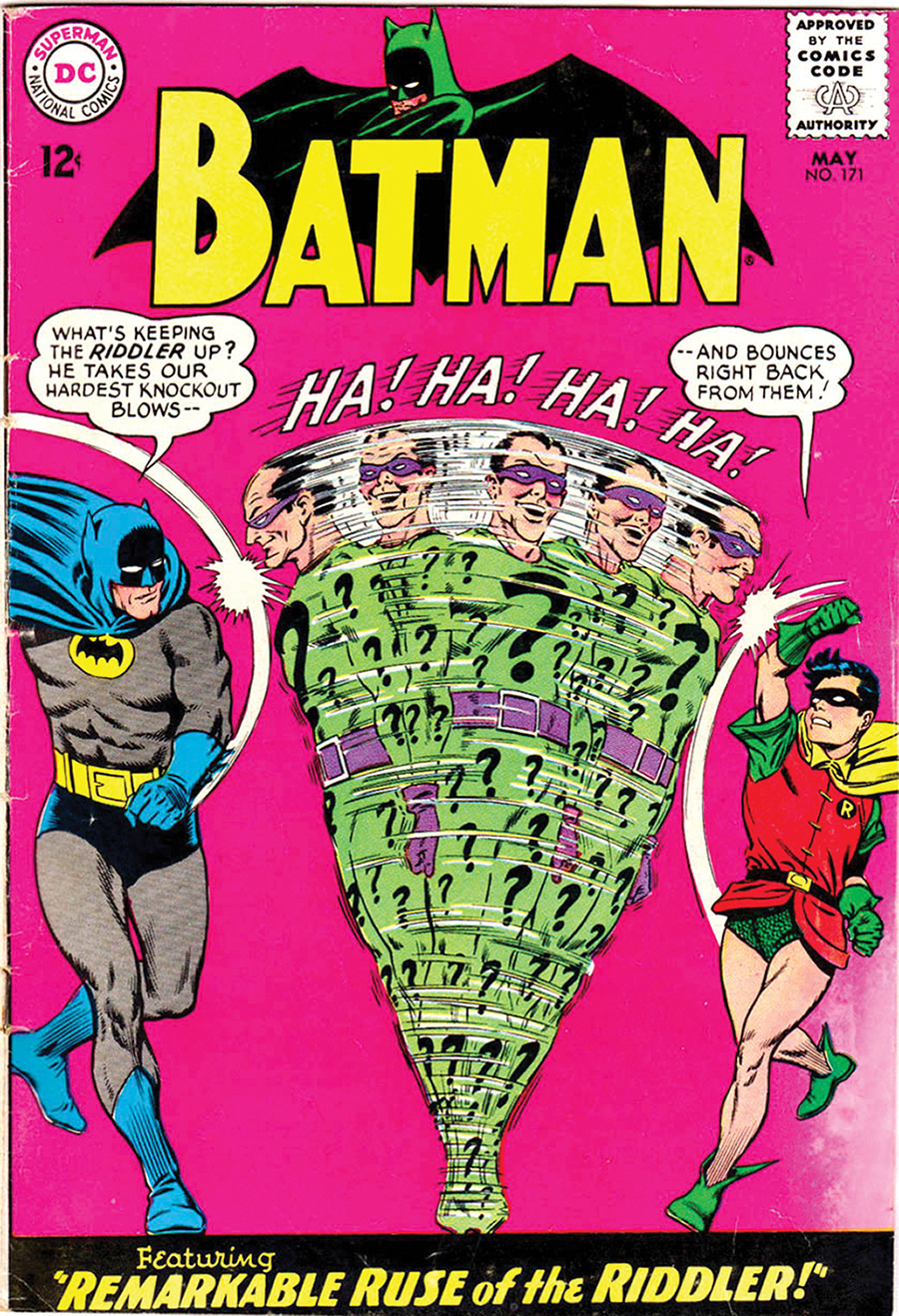

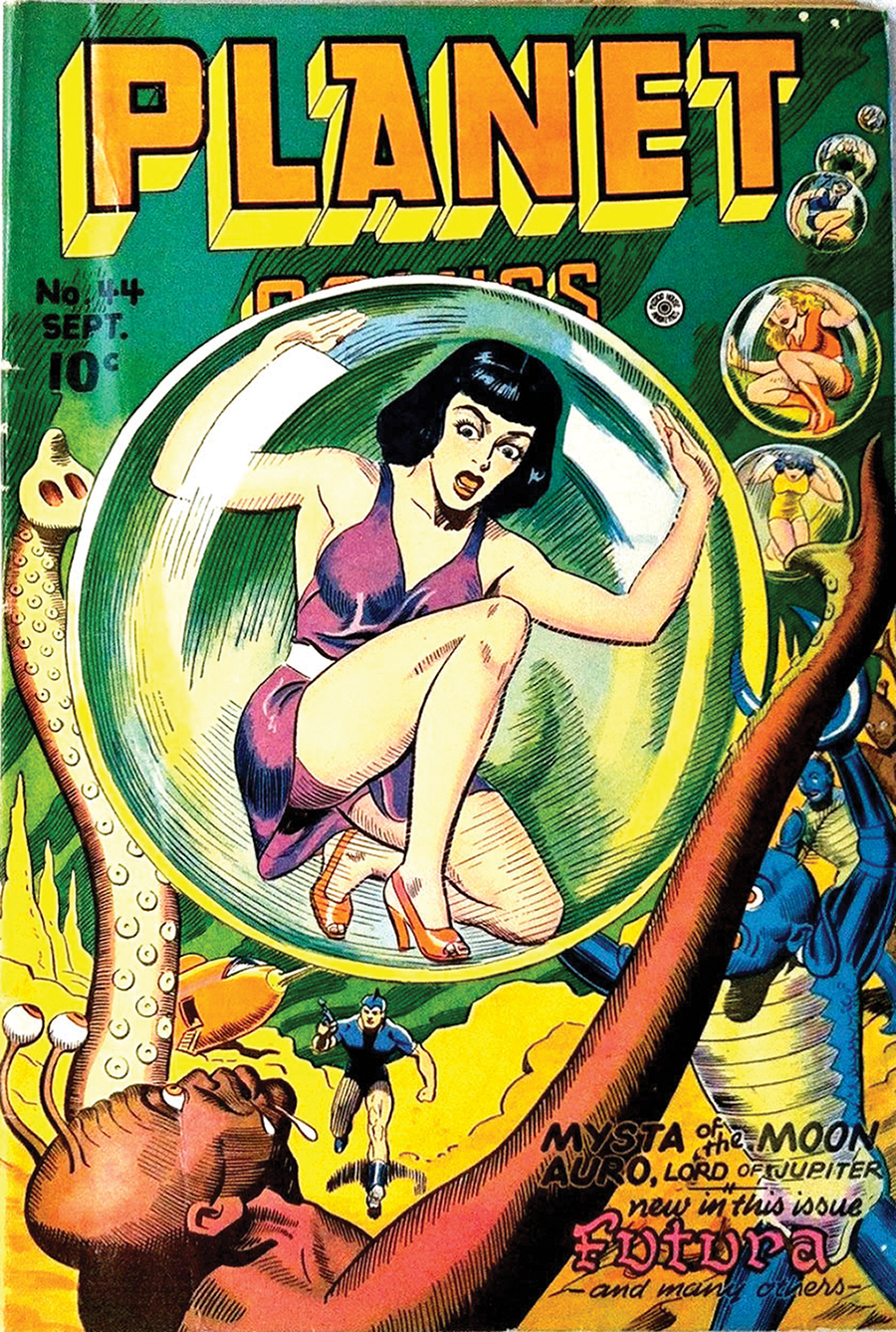

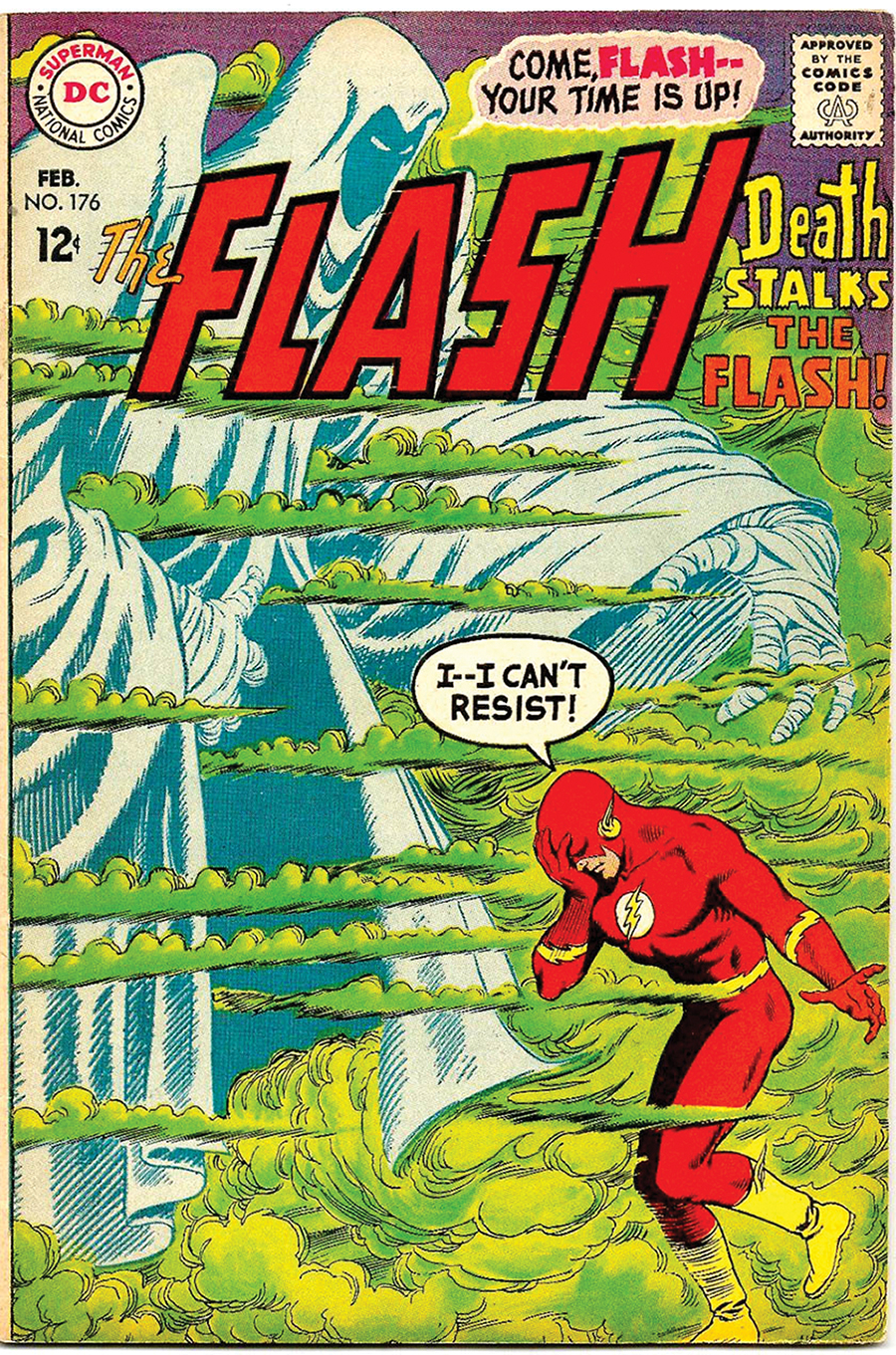

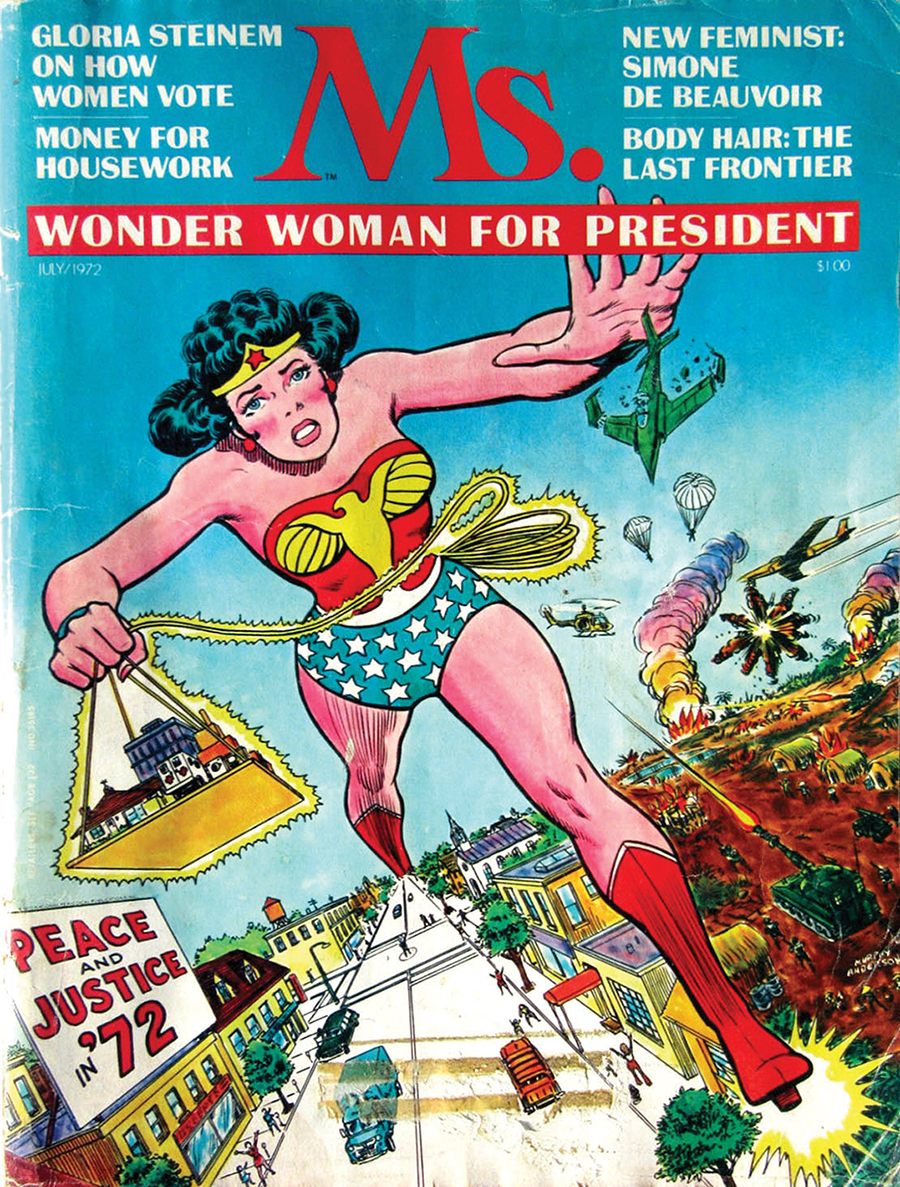

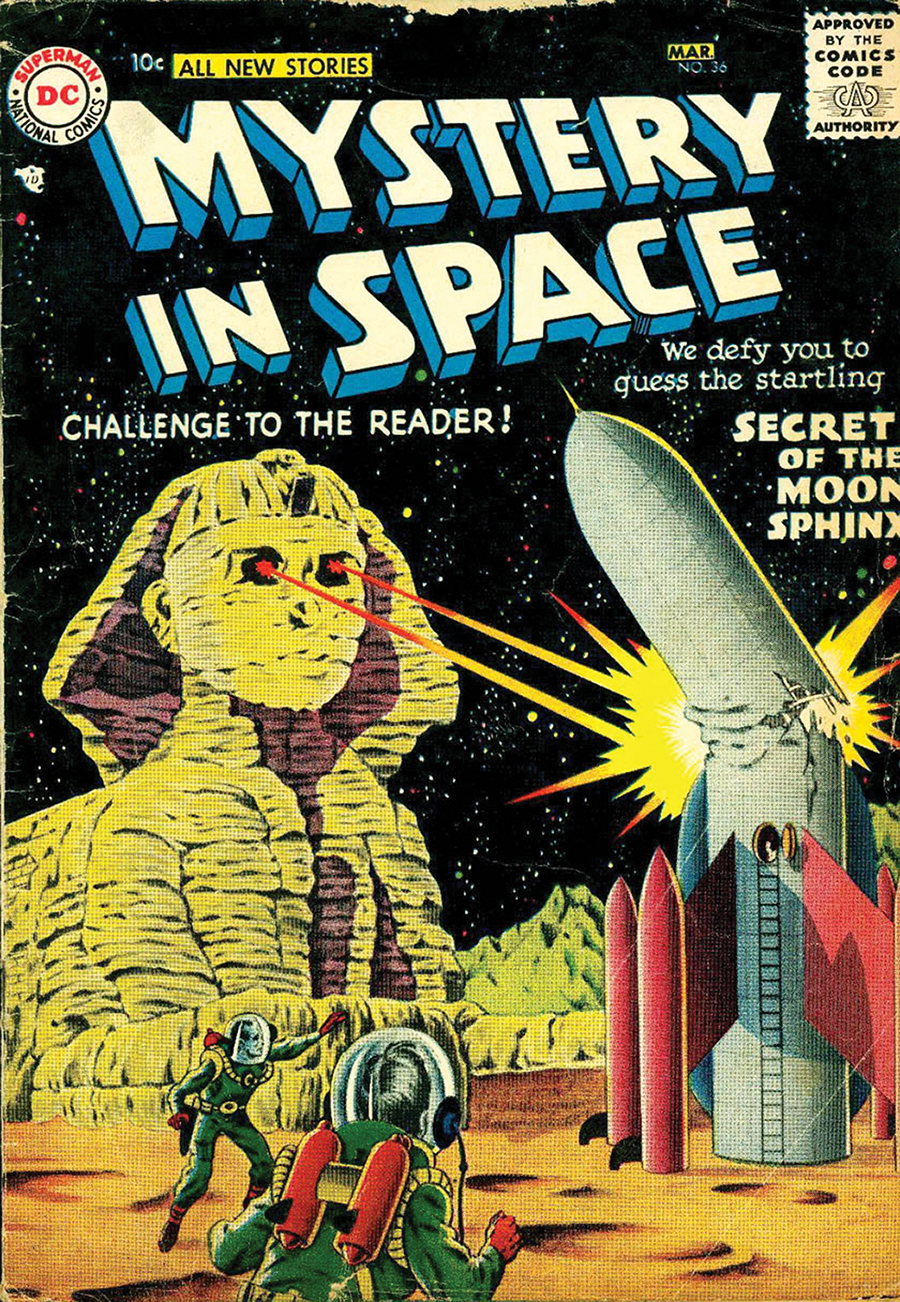

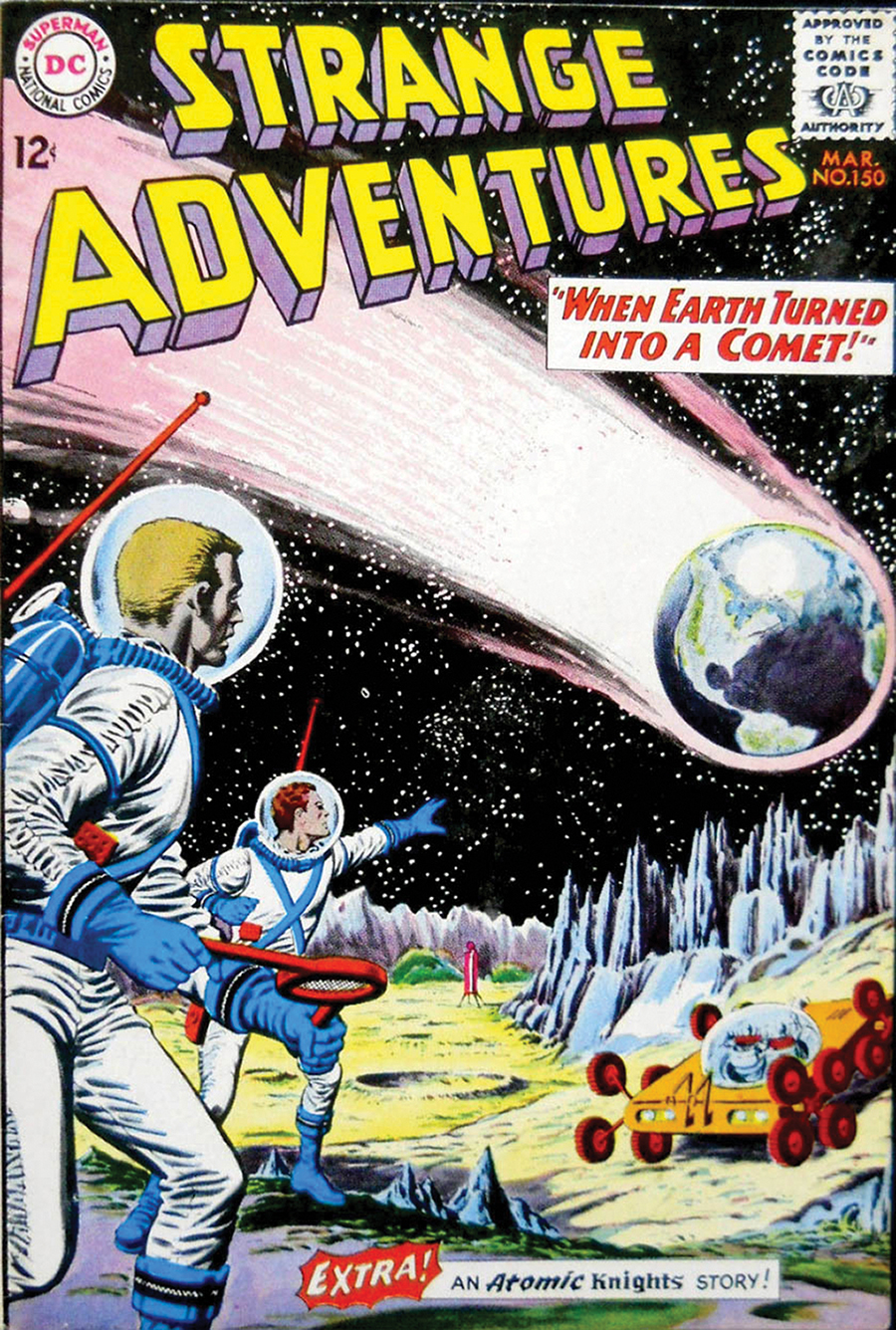

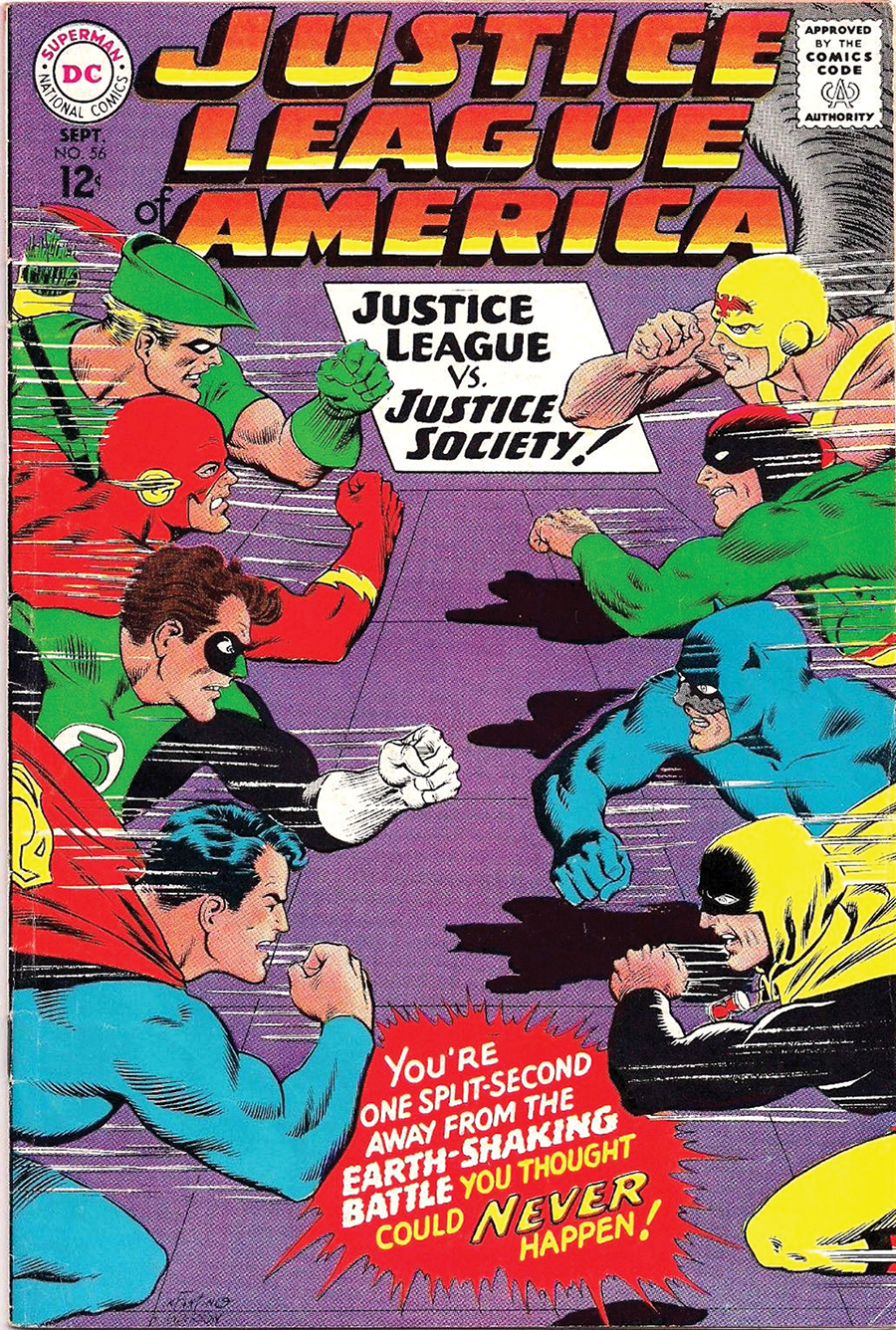

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

Perhaps you know that saffron, the complex and costly spice, comes from the red stigmas of the autumn-blooming saffron crocus (C. sativus), not the snow crocuses you see now, bursting through the frozen earth. And yet, these winter-blooming beauties offer something of even greater value: the ineffable promise of spring.

Perhaps you know that saffron, the complex and costly spice, comes from the red stigmas of the autumn-blooming saffron crocus (C. sativus), not the snow crocuses you see now, bursting through the frozen earth. And yet, these winter-blooming beauties offer something of even greater value: the ineffable promise of spring.