Greensboro’s Jeanaissance

Greensboro’s Jeanaissance

One legacy at a time, denim is on the rise again

By Billy Ingram • Photographs by Mark Wagoner

It was a solemn promise Evan Morrison made to his grandmother on her deathbed that would lead to one of the most improbable outcomes imaginable. He’d just returned from grad school in the City of Light and was looking after her. “She asked that I stay here and make Greensboro a better place,” he recalls. Morrison had no way of knowing then that his pathway forward would result in the return of denim manufacturing to our city. Ensconced in his office atop the historic White Oak Mill, he tells me, “We’ve had so many retirees come here just pouring tears, knowing that this still is happening.”

Denim isn’t just in our jeans. It’s in Greensboro’s — and Evan Morrison’s — genes. Growing up in the Gate City, he attended Buttons and Bows day care in a converted mill house where the walls were adorned in navy and gold, the colors of Cone Mills. His mother worked at Moses Cone Hospital and an aunt was a pattern maker at Blue Bell.

What led to Greensboro becoming the denim capital of the world? The path was forged in the 1890s when two brothers with an entrepreneurial spirit moved to the city and built, first, Proximity Manufacturing Company to produce denim, and then, 15 years later, White Oak Mill, the largest denim mill in the world and the largest cotton mill in the southern United States.

Life was unimaginably rugged in the latter part of the 19th century, which found Americans in need of clothing that could hold up against the elements and rigors of farming. Recognizing that largely untapped market, Baltimore wholesale grocers Moses and Ceasar Cone relocated to Greensboro in 1895 to take advantage of that opportunity. A year later, Cone’s Proximity Cotton Mill, so named because of its adjacency to growing fields and cotton gins, began weaving denim for work clothes. Over the next decade, Cone added two more Greensboro plants, Revolution Cotton Mills and White Oak, producing flannels and denim 24/7.

In a loft above Coe Brothers Grocery on South Elm Street, Hudson Overall Company was formed in 1904. Business was so brisk, the outfit opened a much larger denim factory a block away on South Elm and Lee Street (now Gate City Boulevard) in 1919. Renamed Blue Bell, it became the world’s largest overall manufacturer. Over time, it bought up various regional brands, including Casey Jones Overall and that company’s nascent, largely unrealized Western line, Wranglers. Blue Bell hired Ben Lichtenstein, aka Rodeo Ben, a famous tailor to professional cowboys, movie and bluegrass stars, to design what they called Blue Bell’s Wranglers brand. Introduced to the public in 1947, the name was later shortened to Wrangler.

Organized, it’s been said, by disgruntled Blue Bell employees in the 1930s, Greensboro Overall Company began operations on Carolina Street, manufacturing less expensive Blue Gem coveralls. Both companies’ products were made from Cone fabric. Blue Gem’s label with the radiant gemstone states proudly, “Made of CONE deeptone® DENIM.”

By the 1940s, Cone Mills was number one in the world for denim production, world leader for indigo consumption and world output leader in denim fabric. Levi Strauss & Co. in San Francisco was becoming increasingly dependent on Cone for its 501 line of blue jeans that had become an unlikely fashion statement almost overnight.

At White Oak during the peak years, 3,000 looms were aligned in rows down a cavernous corridor stretching outward so far that if you were positioned at the end of the line, bent down to floor level, and looked forward, the curvature of the earth would only allow you to see where the floor and ceiling converged.

Already in possession of the Lee brand, VF Corporation acquired Greensboro Overall Company and Blue Bell in the 1980s. The Blue Bell label was scuttled while the company focused on Wrangler. VF’s strategy? If their products couldn’t beat the number one jeans manufacturer, Levi’s, having both the number two and three spots would result in more combined sales. It worked and, by the time VF relocated its headquarters to Greensboro in 1998, it had become the world’s largest publicly traded apparel company.

As Evan Morrison pondered the future following his grandmother’s passing in 2013, “I knew I wanted to work in denim. That’s what our city’s known for.” At that time, there were only eight denim mills operating in America. Locally, Cone’s White Oak Mill was running full tilt with several months lead time. “Made in the USA was a major selling point then,” Morrison recalls. “I thought, ‘Well, there’s no brand in Greensboro making jeans or denim products out of cloth woven in Greensboro. So if we start a business like that, we could be the only one of our kind in the Western Hemisphere.’”

Morrison partnered with William and Tinker Clayton to create Hudson’s Hill in 2013 to market clothing and accessories made from Cone denim. Things were going well until, in 2017, Cone announced that their only active mill, White Oak, was ceasing operations, despite producing 1 million yards a year with 46 weaving looms running nonstop. With that closing, a 122-year legacy of denim manufacturing in Greensboro came to an abrupt end with no reasonable expectation that it would ever return.

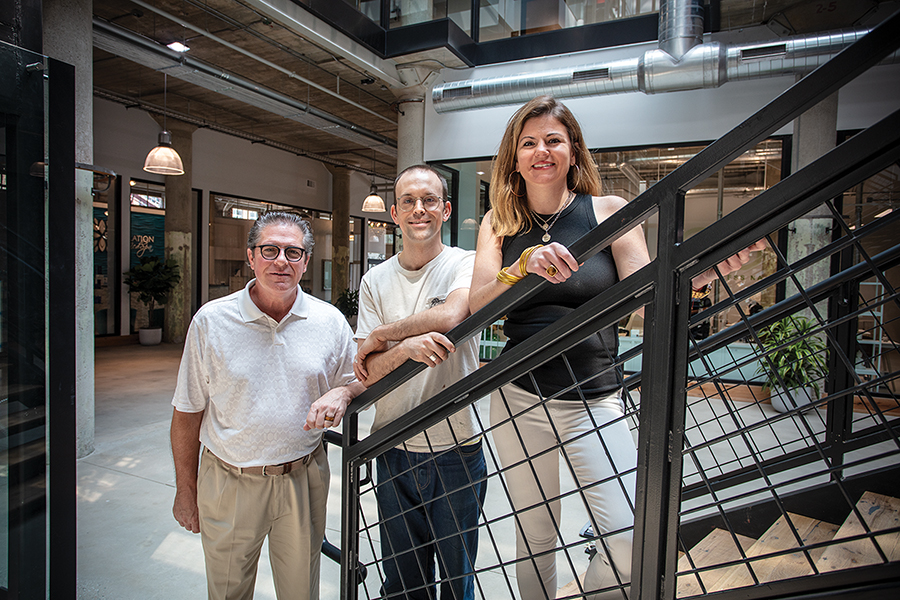

L to R: Evan Morrison, Chip Hardeman, Bud Strickland, Debbie Lindsey and Greg Redelico, representing Proximity Manufacturing Company, a weaving business producing selvage denim woven on Draper shuttle looms at White Oak Mill. Morrison is director of operations; Hardeman is general manager; Strickland is on the board of advisors; Lindsey is a weaver; and Redelico is superintendent.

“It was like, ‘Oh my God, what are we gonna do?’” Hudson’s Hill’s business model had just imploded. “I cold-called and met with the new owner of the property, Will Dellinger, who owns JW Demolition.” Morrison posited that Cone denim’s methodology was the equivalent to Coca-Cola’s secret recipe. “This is the house that made Levi’s, Blue Bell, Lee, OshKosh and Carhartt famous — when a pair of blue jeans became iconically American. People immigrating to the U.S. have a vivid memory of their first pair of jeans. It was a symbol of a better life.”

In 2019, with an agreement in place to lease a portion of the White Oak Mill, Evan Morrison and a group of business professionals across the state formed a nonprofit called the White Oak Legacy Foundation, or W.O.L.F. Morrison approached Cone Denim, asking if they could take possession of the remaining two looms at White Oak with a promise that somehow they’d figure out a way to put them to good use. “We drew up a deed of gift that basically says they’ll give them to us through the nonprofit.” When Cone donated those last remaining looms, Morrison points out, “Essentially, they gifted them to the city. So the people of Greensboro now own our history. W.O.L.F. is the nonprofit that cares for it.”

Original founders of Denim 101 Jill Amidon Strickland and Bud Strickland, shown here, helped W.O.L.F. relaunch an education program in 2021 through volunteering. The rebooted Denim 101 has become so popular that every course has a waitlist. When the couple first launched the program several decades ago while working for Cone Mills at White Oak, Bud worked in product development and Jill worked in quality assurance.

An abundance of Cone Mills veterans in the area possessing a decades-long understanding of supply chains and contacts helped W.O.L.F. map out a workable business plan. “So we started renovating these looms in December of 2019 and, by March of 2020, we were ready to fire them up,” Morrison recalls of the initial run. “We wove our first couple of inches and then, of course, all the plastic parts that had dry rotted broke. So it took another month to find all those parts and rehab the machines to get them back up and running.” By May, those looms were weaving five days a week, “but they don’t weave very fast.” For Morrison, that presented a challenge. “I have an M.B.A., and an entrepreneurial spirit. So let’s figure out how to do as much as we can with what little we’ve got.” Know how to spot a true entrepreneur? “I do all the machine fixing and all of the rebuilding myself,” Morrison says.

L to R: Nick Piornack, Evan Morrison, Karen Little, representing Revolution Mill, located in NE Greensboro, formerly the world’s largest flannel and corduroy mill and part of the Cone Mills family of textile mills, now historically renovated and owned by Self-Help. Since 2013, it has hosted a collection of textile exhibits, ephemeral objects and historical equipment that has helped showcase its history throughout its mixed-use campus. Nick serves as general manager, Evan oversees special projects, while Karen serves as property manager at Revolution Mill.

W.O.L.F. has four defining pillars: Make, Remember, Learn and Create. Working looms represent the “Make” portion of W.O.L.F. “Remember” is being manifested as an American Denim Museum downstairs at White Oak on the heels of Morrison’s previous historical installations at various locations over the last decade. Cruise around town and you’ll spy statues of pairs of blue jeans put in place when Evan Morrison first coined the moniker, Jeansboro, now synonymous with our city.

“The ‘Learn’ side is Denim 101,” Morrison explains. “There used to be a big event here called The Denim School. Designers would come for a couple of days and learn, from bale-to-fabric-to finishing, how things actually got made.” By chance, his across-the-street neighbors, Bud and Jill Amidon Strickland, founded that program in the ’80s. “I asked them to come back on and help us. We’ve put on six sold-out programs and everybody from Gap to Levi’s, Lee, Wrangler, Cone Denim, Cotton Incorporated, with students from N.C. State, A&T, UNCG all attending.”

The “Create” aspect means staying on the cutting edge, just as Cone Mills was recognized worldwide for modernizations. “The first air-conditioned plants,” Morrison points out. “First to develop ‘S’ jeans, which is like a recovery denim that has stretch but doesn’t stretch out. First to weave denim with the new, natural indigo being grown in the United States. So many firsts.”

That spirit of innovation lives on at White Oak. The first pair of jeans in the Western Hemisphere woven on shuttle looms with hemp as a component was recently developed there. “Last year, we wove some of the first ever bio-based, plant-based indigo,” Morrison notes. “It doesn’t use any chemicals, just natural elements.”

To attain a custom shade of denim for a more distinctive look, 20,000 linear yards of yarn has to be ordered. “We can only handle about 4,000,” Morrison says. In order to act big but stay small he came up with the idea of “weft out.” In a typical pair of jeans, “the blue that goes through the loom is called the warp and it gets filled with what’s called weft.” Generally, that weft is white, creating the lighter hue you see inside your jeans. “I thought, ‘What if we just flip the fabric backwards?’ So we started Weft Out, which is our trademark, using filling yarn to create a custom color.”

Morrison unfolds a bolt of a fabric revealing an astonishing effect — vibrant hues of turquoise, gold and orange, with indigo playing a supporting role on the back side. “This is something that we sell to really high end fashion companies for $3,000 [per pair of] jeans. It does take a lot more time.”

A little closer to home than $3,000 jeans, one hopes, is the aforementioned Hudson’s Hill, where Evan Morrison began this journey ten years ago, a stylish storefront situated next door to where Hudson Overall/Blue Bell was established well over a century ago. Stocked exclusively with products made in America, with a hefty percentage produced right here in North Carolina, I liken it to shopping at the Ralph Lauren store in Beverly Hills, albeit more compact.

Inside Hudson’s Hill, hip haberdasher J.R. Hudgins points out a line of jeans not likely found outside of New York or Los Angeles, saying, “Tellason is like an entry level gold standard for the shop right now, affordable for an America made pair of jeans.” A grouping of classically styled jackets catches my eye. “These are from a company called Mr. Freedom,” Hudgins says. “I love them because he’s a French designer who has a very Western aesthetic but with a European cut, higher cut arm holes, much trimmer body, not as boxy.” There are, of course, store-branded jeans and jackets constructed from found dead stock: “Fabric Cone Mills or another local producer stopped making and we found enough to make some pants or jackets out of it,” he explains. “Once these sell, that’s it.”

L to R: William Clayton, Tinker Clayton, Evan Morrison and John Hudgins, representing Hudson’s Hill: The Last Great American-Made General Store, located in downtown Greensboro on S. Elm Street. The Claytons (father and son) and Morrison are co-owners, while Hudgins serves as store manager.

E-commerce aside, Hudson’s Hill’s local customer base is augmented by visitors here on business from larger cities and abroad. “That’s the clientele for a lot of the higher ticket items,” Hudgins says. “Yes, if our store was in Brooklyn, we’d probably be a lot more successful. But we couldn’t do things the way we do if we weren’t here in Greensboro.”

Headquartered on Green Valley Road, Cone Denim still operates factories in Mexico and China, and — as you read this — it’s relocating its headquarters to Revolution Mill. The circle of life and all that. And still innovating with Flash Finish technology and Mission Zero Waste to be more eco-efficient.

Adjacent to Evan Morrison’s workspace/studio at nearby Revolution Mill, old Cone manufacturing equipment sits on display. “I might be leaving my work at the end of the day, kind of frustrated because something’s gone wrong,” he tells me, “and I’ll walk out of my office and look over and there’s a granddad [crouching down] with his grandkid telling them, ‘I used to work on these machines in this building when I was a young person.’ And that’s the tackling fuel, to quote The Waterboy.” OH

Those interested in Greensboro history might find Billy Ingram’s book, EYE on GSO, to be perfect summer reading. Available from bookstores and on Amazon.

The Legacy of Moses Cone

© Carol W. Martin/Greensboro History Museum Collection.

Just months after the employees of the combined Proximity, White Oak and Revolution Mills celebrated their fourth annual picnic in 1908, newspapers around the country proclaimed that Moses Cone, the “Denim King,” was dead at the age of 51. However, weaving and manufacturing of denim in Greensboro was still in its infancy.

Having left no last will and testament, under North Carolina law, 50 percent of Cone’s estate would have to be surrendered to the state. His brother, Ceasar, and Moses’ wife, Bertha, negotiated with state officials to park his holdings into an account, allowing Bertha to live comfortably until her death in 1947.

Moses Cone holding his niece, Isabel Cone, ca. 1907.

Photograph © Greensboro History Museum Collection

Per that aforementioned agreement, that trust was then donated, along with a sizable patch of centrally located real estate, for the construction of a hospital to be named for Moses Cone. But there was one stipulation: If the Cone name ceased to be associated with the hospital, ownership would revert to Moses’ living descendants.

That’s why, no matter how many times Cone Health may be purchased, merged or rebranded, the name Cone will always be front and center.

Big Screen Jeans

Right: Stranger Things, Left: Yellowstone

Greensboro’s own Wrangler jeans are taking a noticeable star turn on hot TV series like Yellowstone and Stranger Things. Truth to tell, if you recognize any label or logo in the scene of a television production, it’s almost certainly paid for.

Product placements are a bit more subtle today than back in the 1980s when characters would play an entire scene in front of a Pepsi machine. Or, think back upon ET’s intergalactic hunger for a relatively unknown candy, Reese’s Pieces, considered the first mega-successful product tie-in of all time after M&Ms passed on the opportunity.

Wrangler’s first product placement campaigns started back in 1947 when their rough-and-ready denim jeans were first introduced to the public, leather labels stitched on the backsides of big name rodeo stars to reach the targeted rugged individual demographic. To a certain extent, that still holds true.

Wrangler is only one of a number of Triad companies that have been purposely inserting their products into scenes and sponsoring television programs since the medium’s earliest days. With deep pockets, Big Tobacco was one of the first industries to see the potential in television. In fact, in the 1950s and ’60s, sponsors had more control over the content of TV programs than the networks did.

Walker

Walker

Headquartered in Greensboro, P. Lorillard Tobacco Company sponsored classic shows like Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour, which found Old Gold’s Dancing Cigarette Pack and The Little Matchbox tap-tap-tapping across the small screen in the early-1950s. Lorillard’s Newport logo was featured prominently on ’60s sensations like The Price is Right and Petticoat Junction.

R.J. Reynolds took an integrated sponsorship approach with seamless transitions as a primary advertiser on The Flintstones when that cartoon series debuted in 1960. “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should,” especially when Fred Flintstone and Barney Rubble would sneak around the cave to light one up while the wives continued doing all of the chores. Camels became synonymous with The Phil Silvers Show.

Reynolds’ Kent cigarettes sponsored The Dick Van Dyke Show. Cast members happily puffed away in one minute skits while Steve McQueen stepped out of character to peddle Viceroys on Wanted: Dead or Alive. Vicks VapoRub, manufactured (until 1985) by Greensboro-based company Richardson-Vicks, was another ubiquitous TV advertiser in the 1960s and ’70s.

In 1952, Greensboro’s Burlington Industries became the first textile manufacturer to advertise on television. By the 1960s and ’70s, its brash, bold, percussive spots became woven into the fabric of nighttime television, punctuating programs like The Waltons and The Mary Tyler Moore Show. When Burlington did its yearly opinion survey in 1975, 70 percent of those sampled recognized the brand from watching television.

So the next time you spy a pair of men’s Greensboro jeans on a Western-themed show like Walker or Outer Range, know that Wrangler is continuing a decades-long tradition of Triad firms influencing the television programs we watch in both large and small ways.

The Dog Days of summer are upon us, but don’t sweat it. We’ve got some ideas to help you keep your chill.

The Dog Days of summer are upon us, but don’t sweat it. We’ve got some ideas to help you keep your chill.