A seasoned hiker shares five favorite trails

By David Claude Bailey

As a travel writer and former airline-magazine editor, I’ve visited a mountain or two — Mount Olympus, the seat of Zeus in Greece, the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon, Mammoth Mountain in California, the Grand Tetons, and Yellowstone. But all mountains are not created equal. Without getting New Age woo-woo on you, on some of them I get a feeling that transcends the five senses, an eerie, almost spiritual sense of connection.

I felt it first at Delphi, the ancient precinct that was home of the Delphic oracle. I felt it again among the ancient ruins near Ayacucho in Peru. And I feel it every time I go to the Uwharries, a Piedmont mountain range near Asheboro, where the peaks have been worn down from a whopping 20,000 feet to a mere 1,100.

How did that happen? More than 500 million years is one answer. When you tread the trails along Big Island Creek, you are walking on ground that belonged to the ancient landmass of Gondwana, a megacontinent that was once part of modern-day South America and Africa. Somewhere between 460 and 430 million years ago, part of Gondwana broke off and merged into ancient North America, piling up the Uwharrie mountains. Books and websites insist the Uwharries are the oldest mountains in North America, but that’s by no means the case. “The Rocky Mountains are between about 70 and 35 million years old,” says Kevin Stewart, a UNC Chapel Hill professor in the department of Earth, marine and environmental sciences. “Ancient mountains in the northern midwest stretch back to 2.5 billion years,” he says. And you want really old? Some mountains in South Africa are 6.3 billion years old.

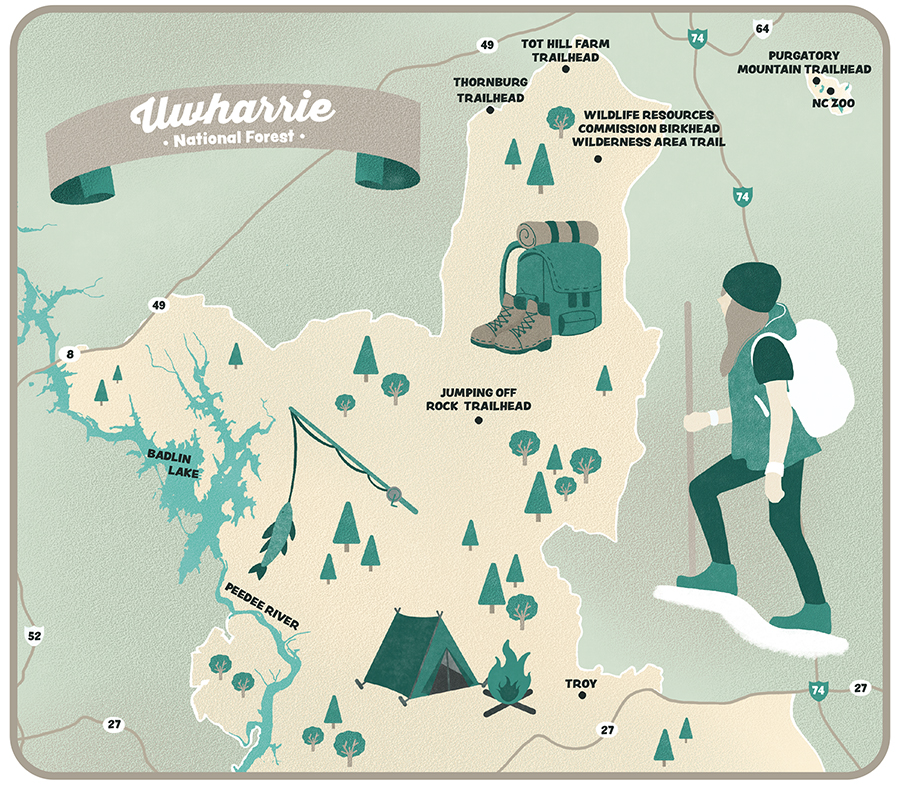

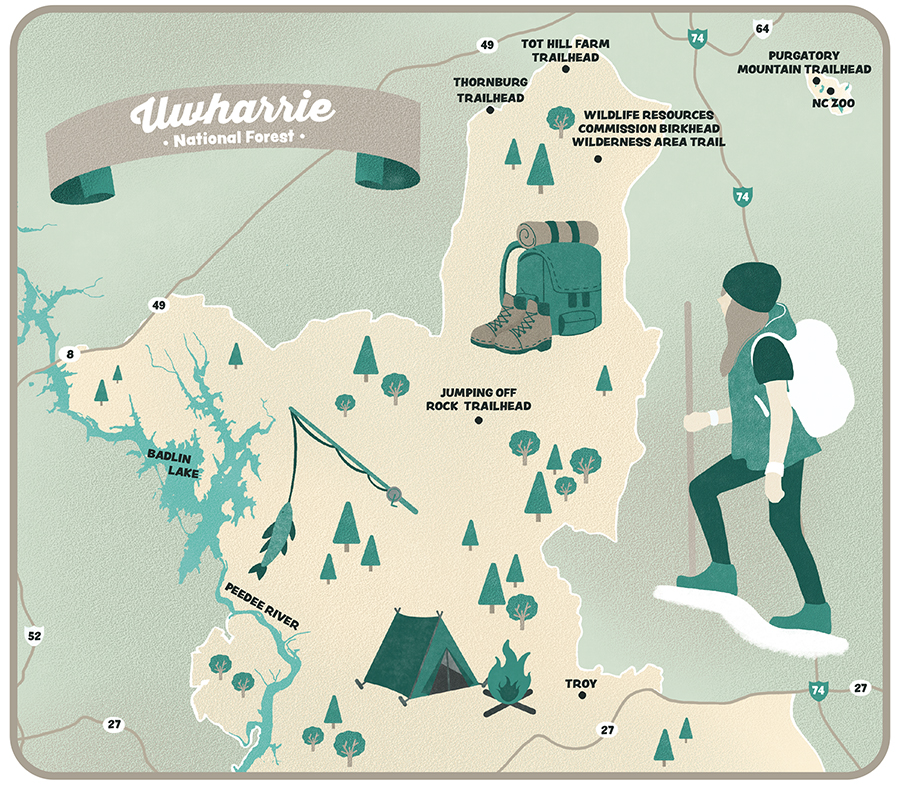

In more recent years, the Uwharries have been the scene of gold mining, timbering, farming, bootlegging and, now, recreation, especially in 2023, N.C.’s official Year of the Trail. Running from south to north, the Uwharrie Trail is the longest single-track footpath in central North Carolina at 40 miles in length. Numerous other trails snake through the 52,000-acre National Forest, established in 1961.

What I’ve attempted to convey here is a thumbnail, a personality portrait, if you will, of five of my favorite trails, paired with a number of unique hiking partners. This is not a hiking guide. Excellent guides to individual trails are available from websites such as alltrails.com and gaiagps.com. Don Childrey’s comprehensive Uwharries Lake Region Trail Guide covers more than 215 miles of trails in the area. I urge you to consult a guide or map before setting out. And happy trails.

Jumping Off Mountain Trailhead

Length | Two hikes are available from

the trailhead, an 8-mile out-and-back and a 3.9-mile out-and-back.

Difficulty | Both hikes are challenging with significant elevation gain.

Dontʼt Miss | The sign in the parking lot that outlines a number of other nearby hikes.

Good to Know | The actual Jumping Off Rock, if you want to see it, is west, just a hop, skip and a jump up Flint Hill Road on the left.

Address | 2015 A Flint Hill Rd., Troy

“Keep on the sunny side, always on the sunny side, keep on the sunny side of life,” the Carter family warbles, and it’s not bad advice. If a sunny walk in the woods is what you want, get yourself to the Jumping Off Rock Trailhead. Cross Flint Hill Road and hike up about a half-mile to the overnight camp cabin. There, you can enjoy a stunning, 360-degree view of the Uwharrie Mountains and have a picnic while reading the camp log. Keep going and you’ll bag an exhilarating 8-mile out-and-back hike to King Mountain, the highest point on the Uwharrie Trail.

However, as A.P., Sara, Ezra and Maybelle admit in the very same song, “There is a dark and a troubled side of life.” And maybe that’s just the sort of thing that appeals to you. If so, don’t cross that road. Trek right up in the shadow of the appropriately named Dark Mountain, as recommended in An Afternoon Hike into the Past, penned by the late Joe Moffitt, a trapper’s son who grew up in the Uhwarries during the Great Depression. That will put you on a trail trod by murderers, moonshiners, and the odd haint or two. Which is what we did.

Mind you, the switchbacks up Dark Mountain are challenging. Gaining 400 feet of elevation in less than a mile, twice, hikers not quite as old and in the way as we are pass us. After about three-quarters of a mile, you reach the ridge line. Follow the white blazes on the Uwharrie Trail and you’ll enjoy a glorious 3.9-mile out-and-back jaunt.

But we’ve come to see Paint Rock, which we look for along a deserted road to the left. “They all look kind of painted,” says Lin Marie, pointing to dark spots and orangish-brown splatters that are clearly lichen. A naturalist who worked for a nature museum and a state park, Lin knows a thing or two about plants and fungal identification. As we’re poking around, she briefs us on how fungal substrates allow fungi to respond to changing availability of resources. And how she’d just read a book on the way “mother trees” communicate with their offspring.

Lin is our resident polymath. If she doesn’t know it, she’ll look it up on the spot.

But back to Paint Rock. Moffitt, the legendary Uwharrie Trail-blazer, insists in his book that there’s a rock in the woods that still “bleeds” from where a giant man ran his sword through a diminutive Civil War deserter. As far as we can tell, there are numerous Paint Rocks. And maybe that fits Moffitt’s narrative: Three Civil War deserters were murdered near Dark Mountain in 1865. Bootleggers also killed two revenuers at nearby Licker Spring. And all of this in the environs of Jumping Off Rock Trailhead, named after another story that did not end well, as you might guess.

As we come across some of the largest boulders in the forest — larger than dumpsters and the Nifty Rocks near Badin Lake — Lin, who helped Ohio State monitor butterflies for 15 years, is on the lookout. Lin, by the way, raises moths, which she adores. Honeybees not so much. “Alien invaders,” she calls them, just like earthworms. “Look it up,” she says, as we stare at her in disbelief.

We don’t find the cave where a bootlegger and his family once hid out. Nor do we see the ghost of the sacred white deer slain by Indian braves, nor any of the other ghosts Moffitt wrote about inhabiting the area. But as Moffitt observed, wandering around these shady hills is a bit unnerving: “I always seemed to feel as if someone is watching me.”

Better to get back in the sun and remember what the Carters sang about the sunny side: “It will help us every day, it will brighten all the way, if we’ll keep on the sunny side of life.”

Thornburg Trailhead

Length | 3.4 miles out and back, with side trails.

Difficulty | Moderately challenging with a fair amount of elevation gain.

Dontʼt Miss | The rocks strategically paced across the creek near the bridge.

Good to Know | As Wilder noted, it can be quite muddy.

Address | 3977 Lassiter Mill Rd., Asheboro

Getting Wilder out of his car seat when he’s raring to go is a little like untangling an octopus from a ball of yarn. So as soon as Cassie, his mom, finally gets his feet on the ground, he rips off across the farmyard like the Road Runner pursued by Wile E. Coyote.

“STOP!” the 4-year-old shouts all at once, holding up his hands as if to stop a train in its tracks. “I love birds,” he proclaims at the top of his voice, scaring away every song sparrow, robin, purple finch and chickadee within 100 yards. And as soon as he sees the circa 1850, two-story, apple-green Lewis-Thornburg farmhouse, surrounded by scraggly boxwoods, he also announces, “I love farmhouses.” Charging full throttle onto the porch, he’s fascinated by the screen door with its self-closing wheeze and whine, followed by a shuddering slam — for a solid minute.

The National Register of Historic Places’ listing says not to miss the rambling farmhouse’s wide, heart-pine floorboards, the square balusters and moulded handrails on the staircase, the narrow, distinctive beadboard on the walls and ceiling. Wilder, though, is entranced by the mix of soot, feathers and leaves that have spilled out of the chimney onto the circa 1940s linoleum.

“I love holes in the wall,” he says of a crawl-space door left open on the second floor. Spotting a trap door overhead, I boost him up through the cutout and after peering around into the dim recesses off the attic, he says, “Spooky.” It is.

Ripping down the stairs, we’re on the back porch by the kitchen, where the well crank makes a mournful moan. Again and again and again.

“I love tractors,” Wilder says, lighting out across the yard to a brand spanking new John Deere behind the house. “Where’s the key?” he asks as he clambers up the steps and peers into a locked compartment where the shiny gear shift and steering wheel beckon.

Then it’s shed exploration time. “Well, guys, someone’s been working here,” he says, discovering a coffee can filled with screws and nails in a tool shed. On to the corn crib, smokehouse, chicken houses, dog house, pigeon boxes, tack shed, hog shelter, animal chute . . . and an outhouse! Cassie restrains the Wilder unit from going head over heels through one of the two-seater holes. “Ewwwww, yucky,” he says as it dawns on him what’s what.

Finally, we’re on the actual trail heading down toward the creek. “STOP!” he says, stooping over. “Sparkles!” Yes, the red mud is alive with tiny, shimmering mica bits. Specimens of quartz from tiny to basketball-sized are everywhere, pieces of which he stuffs into his already overloaded pockets. On a little side trail across sage brush beaten down by rabbits, possums and the previous day’s rain, we’re soon surrounded by milkweed pods, which explode into a white flurry that swirls off into the wind, seeding next year’s crop.

Back on the main trail, Wilder halts progress again: “It’s a little ocean,” he pronounces as Cassie navigates him around a mud puddle, which Wilder stirs with a stick like a pot on the stove. A bridge twisted catawampus crosses Betty McGee’s creek. “Want some help?” Mom wonders. “Nawp,” he says, clamoring perilously near the creek. Then: “I can’t. I can’t. I can’t,” he admits. Pieces of bark torn from a shedding tree quickly become boats, which race down the creek. A pair of termites are minutely examined before they, too, float downstream.

We veer off onto another game trail and snake the edge of a field, where blackberry brambles soon occasion a cry of “Ouchy, ouchy, ouchy,” but no tears. “Snack,” comes to the rescue.

“STOP! It’s a gem,” Wilder says, holding up a rare piece of rosy quartz. No room left in his pockets, he casts it aside. “This is Quartz World,” Wilder decides. And he’s absolutely right. It might just be the second most magical place on Earth.

Purgatory Trail, North Carolina Zoo

“David, the entrance to the zoo is over there,” my wife, Anne, says as I slide into the North Carolina Zoo’s totally empty Parking Lot A.

“I thought we’d take a short walk in the woods before looking at the animals,” I tell her. “You’re gonna climb a mountain today.”

“The sign says ‘Purgatory Mountain,’” my knee-challenged wife points out.

“Trust me,” I say. She’s heard that before.

“It’s a gentle stroll, suitable for people with mobility issues,” I say pointing to a sign. “Even in wheelchairs.”

“The sign says it’s wheelchair accessible for only 0.125 miles.”

And so it is — on a wide path paved with very fine gravel, that too soon segues into a little more rugged trail that winds its way up through towering pines and mature hardwoods. “You’ve hiked 1/8 mile,” says an un-milepost.

“That vulture is following us,” says Anne as its shadow swoops across the fallen leaves.

Through the trees on our right we see the seedy underbelly of the zoo, piles of rocks, dirt and debris. I, of course, want to explore, but Anne keeps me on the not-so-straight and not particularly narrow path. To our left, deep woods and massive boulders the size of baby elephants stretch to the horizon.

“Acadian fly catcher,” my resident birder says. “No, a peewee. No, eastern phoebe.”

We breeze past the sign heralding the endangered Schweinitz’s sunflower; past the sign explaining woodland seeps (small pools), which sometimes harbor the rare four-toed salamander; past the sign marking the half-mile point.

“I’m doing OK,” reports Anniel Boone.

“Elevation 900 feet, with 150 feet of vertical ascent,” I announce after consulting my Gaia GPS app.

At the summit, where we’re congratulated for walking 5,280 feet, it’s 950 feet above sea level, only 60 feet shy of the highest point on the Uwharrie Trail. After enjoying the vista, we read all about ghosts, Indians, legendary critters, bootleggers, Confederate objectors and why the mountain was named Purgatory.

“Maybe because it’s just short of Hell’s Gate,” jests Anne, who, in the end, admits it’s a great trail and worth the climb, mobility issues or not.

“Climb every mountain, ford every stream . . .” I counter, breaking into song.

Tot Hill Farm Trailhead

Length | Our “lollipop” trek totaled 7.4 miles. If you just hiked to Camp 5 and back, it would be 6.4 miles.

Difficulty | More than moderately challenging with 607 feet of elevation gain.

Dontʼt Miss | The gold mines. You can visit them without making the loop by taking a left after 2 miles onto the Coolers Knob/Camp 3 trail. They’re about a mile down the trail.

Good to Know | There’s not a sign on the road marking the Tot Hill Trailhead. Slow down and look for it as soon as you see the golf course.

Address | 3091 Tot Hill Farm Rd., Asheboro 27205

My friend Randall’s German shepherd is a free-range critter. Unlike his urban canine counterparts, the Pia dog is untrammeled by leashes, fences or property lines. Randall lets her out whenever there’s a need . . . and Pia rings the doorbell to be let back in. German shepherds are like that, though she has yet to master the TV remote control. Pia has learned, for instance, how to roll down the rear window of Randall’s truck whenever we sit in the front seat piddling with our GPS apps.

“I’ve got her child-locked in — or maybe I should say dog-locked,” says Randall as Pia paws the rear-window button in the parking lot of the Tot Hill Farm Trailhead, the northernmost point of the Birkhead Mountain Wilderness Area.

Pia’s jet-black “eyebrows” shoot up and down in consternation. She twists her head quizzically to one side as if to say, “Did we come here just to sit around?”

We did not. We came to roam free, just like Pia and the couple of kids we turn back into as soon as we hit the trail. Our playground is the 52,000-plus-acre Uwharrie National Forest that stretches into Montgomery, Randolph and Davidson Counties.

Note that I said National Forest, not park. Under National Forest rules, Pia can run free. As can we. Cross-country trekking is allowed, as is horseback riding, ATV riding, camping, panning for gold, hunting and fishing — all, of course, with some reasonable restrictions. (You must “control” your pets.) While National Parks emphasize preservation of pristine areas, National Forests are managed for many purposes, including cattle grazing, mining and lumbering — permits required.

Our inner child kicks in as we cross Talbotts Branch. We pass the stone remains of a dam and watch Pia sniff dismissively at some coyote scat. At about a mile into the walk, we rest while Pia fetches.

At the tippy top of Coolers Knob our GPS says we’ve clocked 333 feet of vertical ascent in 1.2 miles. We pant. Pia pants. We keep booking it, heading for Camp 5, one of a number of campsites established by Joe Moffitt. In 1972, he started his Uwharrie Trail Project, backed literally by troops of Boy Scouts. Now, 40-some miles of trails later, Pia examines the camp for any scraps of Beanie-Weenies. At the 3-mile mark, we hang a left and take the Camp 3 Trail, which is marked as the Coolers Knob Mountain Trail on some maps. This initiates a loop that will take us back to Coolers Knob. Serious hikers call this a lollipop trek because of its shape on the map. Whatever you call it, it’s one of the most magical hikes in the Uwharries. We descend to the inviting Camp 3 site, checking out an enclosed spring, where we would never drink the water without purifying it first, especially after Pia drinks out of it. Decades peel away and we’re soon frolicking knee-deep in a maze, aptly named fern valley. At 3.9 miles, we cross a cascading brook. A gentle waterfall is punctuated with islands of wildflowers.

At four miles, we come to a series of open-pit gold mines, each of which Pia explores extensively. These are the remains of a gold mining era that began in 1799 when a 12-year-old found a 17-pound nugget of gold in a creek near Charlotte. Farmers riddled their land with open pits and shafts like the ones that surround us. At one time, as many as 600 mines dotted the nine counties surrounding Montgomery County. Randall, Pia and I once panned the Uwharrie’s streams for gold (www.ohenrymag.com/the-pleasures-of-life-dept-15/).

We did not strike it rich. And that’s OK. The riches of the Uwharries are less tangible — its lush vegetation and wildlife, its wilderness, and its storied past. Pia knows all about what, to her, is most precious in the Uwharries: running without a leash, uninhibited by paths and private property. Although I hike for exercise and adventure, I’m always looking for something else — for the child who once roamed free without a care. And for the ties that bind us to the land and to those who inhabited it millennia before we did. Whether it’s the plane crash site a mile from where we are, or the Moonshine Run Trail, or the hike to Bingham’s Graveyard, the treasures of the Uwharrie Mountains always beckon.

Wildlife Resources Commission Birkhead Wilderness Area Trail

Length | 4 miles, more or less, depending on when you want to turn around. It’s not a loop trail.

Difficulty | Easy-peasy. Fairly flat and wide.

Dontʼt Miss | The graveyard if you can find it. And be careful not to venture out of the Wilderness Area. It borders private property.

Good to Know | The entrance is easy to miss. Slow down!

Address | 3800 High Pines Road, Asheboro

“I smell onions,” Randall says.

“My cheese-and-raw-onion sandwich,” Joe replies between munches.

“At least Bailey’s not eating kippered herring. Move downwind,” suggests Randall.

For me, half of the joy of hiking comes from what my daddy called picking at your friends.

“Where’s this slave graveyard,” Joe wonders as we blaze our way through an explosion of hollies, their red berries punctuating dotting the understory of dogwoods and sourwoods.

Randall, who lives in the Uwharries, leads us, again and again, down one remote, wild and off-the-beaten path after another. And that’s exactly what we encounter at the clumsily-named Wildlife Resources Commission Birkhead Wilderness Area Trail. (Let’s just call it the WRCBWAT.) It’s connected to — and about 2.5 miles southeast of — the heavily-trod Tot Hill Farm Trailhead.

By contrast, the WRCBWAT is practically untrammeled.

“This looks more like an old road than a trail,” Joe observes.

“It is, in fact, a former road,” says Randall.

For onion-eating history buffs like Joe, hiking in the Uwharries is like walking back into the pages of a leafy anthology. On our 4-mile trek, we encounter, among other artifacts, a series of abandoned but open gold mines (very common in the Uwharries), the stone remnants of a chimney, vestiges of several homesteads (aka junk piles), the aforementioned graveyard and the ghost of a housing development.

It turns out that the trail we’re on had been graded decades ago by a developer for a 40-unit tract, but was rescued by the Three Rivers Land Trust. That enabled the folks at N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission to buy a prime piece of forest adjacent to the 52,000-acre-plus Uwharrie National Forest, which became the 6,000-acre Birkhead Mountain Wildnerness Area.

Our path surely overlaps the trail of pioneers who’d settled in the area as early as the 1760s, having traveled down the Occaneechi Path (aka Great Trading Path). At least 12,000 years ago, the Catawba Indians hunted in the very woods around us, now designated as N.C. game lands. (Always wear orange in the Uwharries during hunting season.)

“That’s it,” I say, pointing to a flat area. Standing erect in two rows are more than a dozen rough-hewn markers, some larger than others, all without inscriptions. “Maybe tenant farmers. Maybe slaves. Who knows?” I say. “And, yes, I do know ‘enslaved’ is now preferred among politically-correct speakers.”

“Children’s graves,” Randall speculates of the rocks that are the size of serving platters.

“King of the hill,” Joe suggests, pointing to one stone much larger than the rest.

We fall silent, gazing at the markers of those who once lived and loved and worked and played where we now stand.

“You’re never alone in the woods,” I say.

David Claude Bailey is grateful to former Greensboro News & Record columnist Jerry Bledsoe for writing about the Uwharries way back when.

F

F