Birdwatch

BIRDWATCH

Thrush in the Brush

The subtle beauty of the hermit thrush

By Susan Campbell

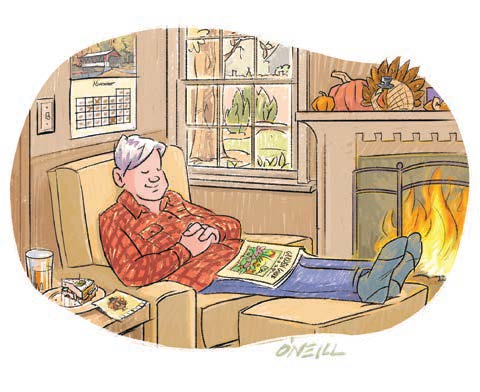

As the temperature and leaves drop, many birds return to their wintering haunts here in the Piedmont of North Carolina. After spending the breeding season up north, seedeaters such as finches and sparrows reappear in gardens across the area. But we have several species that are easily overlooked due to their cryptic coloration and secretive behavior. One of these is the hermit thrush. As its name implies, it tends to be solitary most of the year and also tends to lurk in the undergrowth.

However, this thrush is one of subtle beauty. The males and females are identical. They’re about 6 inches in length with an olive-brown back and a reddish tail. The hermit has brown breast spots, a trait shared by all of the thrush species (including juvenile American robins and Eastern bluebirds, who are familiar members of this group). At close range, it may be possible to see this bird’s white throat, pale bill and pink legs. Extended observation will no doubt reveal the hermit thrush’s distinctive behavior of raising its tail and then slowly dropping it when it comes to a stop.

Since one is far more likely to hear an individual than to see one, recognizing the hermit thrush’s call is important. It gives a quiet “chuck” note frequently as it moves along the forest floor. These birds can be found not only along creeks, at places like Weymouth Woods and Haw River State Park, but along roadsides, the edges of golf courses and scrubby borders of farms throughout the region. It is not unusual for birders to count 40 or 50 individuals on local Audubon Christmas Bird Counts. However, they feed on fruits and insects so are not readily attracted to bird feeders. Over the years, I’ve had a few that managed to find my peanut butter-suet feeder, competing with the nuthatches and woodpeckers for the sweet, protein-rich treat. This tends to be after the dogwoods, beautyberry, pyracantha and the like have been stripped of their berries.

During the summer months, hermit thrushes can be found at elevation in New England and up to the coniferous forests of eastern Canada. A few pairs can even be found near the top of Mount Mitchell here in North Carolina (given the elevation) during May and June. The males have a beautiful flute-like song that gives them away in spite of their camouflage. They nest either on the ground or low in pines or spruces, and mainly feed their young caterpillars and other slow-moving insects.

As with so many migrant species, these thrushes are as faithful to their wintering areas as their breeding spot. I have had several very familiar individuals over the years along James Creek. Keep in mind that if a hermit thrush finds good habitat, he or she may return year after year. With a bit of thick cover, water not far off, and berries and bugs around, there is a good chance many of us will be hosting these handsome birds over the coming months — whether we know it or not.