Sazerac September 2023

Sazerac September 2023

Unsolicited Advice

Every fall since the inception of Pinterest, it happens. Free, pretty printable, “Fall Bucket Lists” in pastels, oranges and sage greens take over the internet. And we think to ourselves, “Yes! This season, I will learn to knit, pick a bushel of apples, make a pie from said apples, preserve colorful leaves and do all the autumnal sort of things!” And then the winter arrives and all you have to show for it is one sad, empty PSL cup with your name spelled wrong. Forget that! We’ve made some updates that’ll have you knocking out this list faster than you can say apple spice cake.

- Bake pumpkin bread. OH: Who has time for that? Buy it at the grocery store and burn that pumpkin spice candle you got last fall. All the vibes with none of the stress.

- Make and sip warm apple cider. OH: Pass us a refreshing hard apple cider, please and thank you.

- Build a scarecrow. OH: Why? What did those crows ever do to you? Instead, make a — really scary — scarehuman and keep those nosy neighbors at bay.

- Go leaf-peeping. OH: Is there a tree outside your window? Look at it. Congratulations, you’ve peeped leaves. Check one off!

- Have a bonfire. OH: Got kindling? May we suggest that fall bucket list printout? Or past issue of OH? Consider it adaptive reuse.

Just One Thing

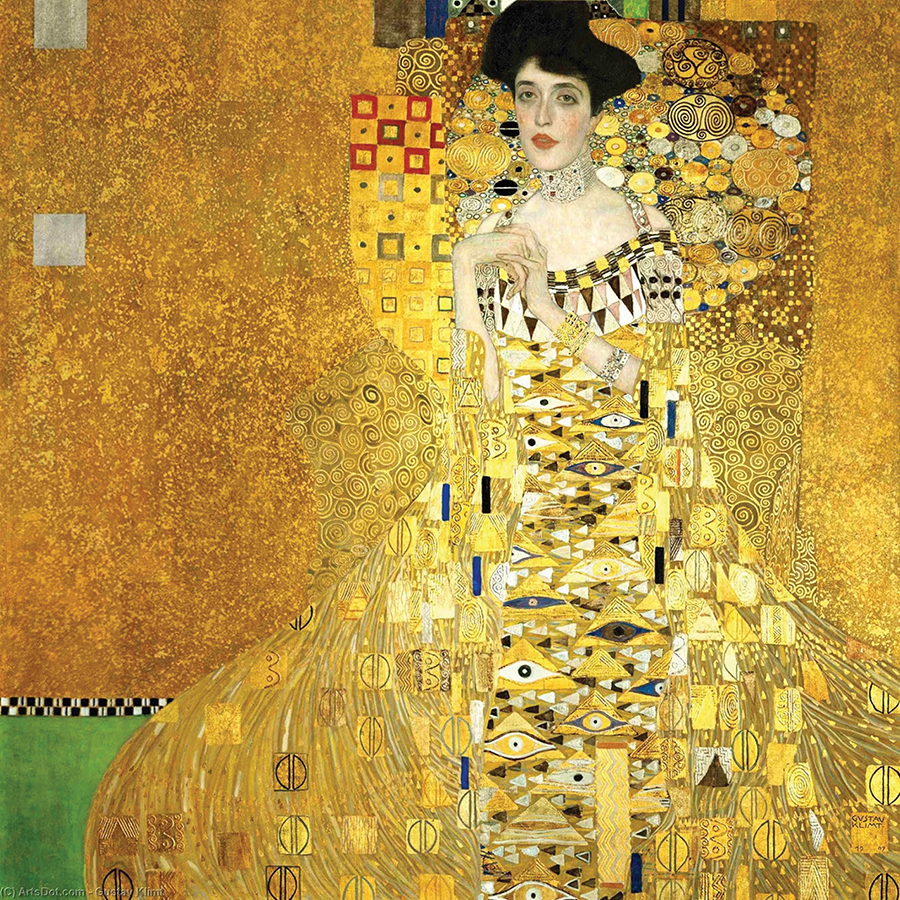

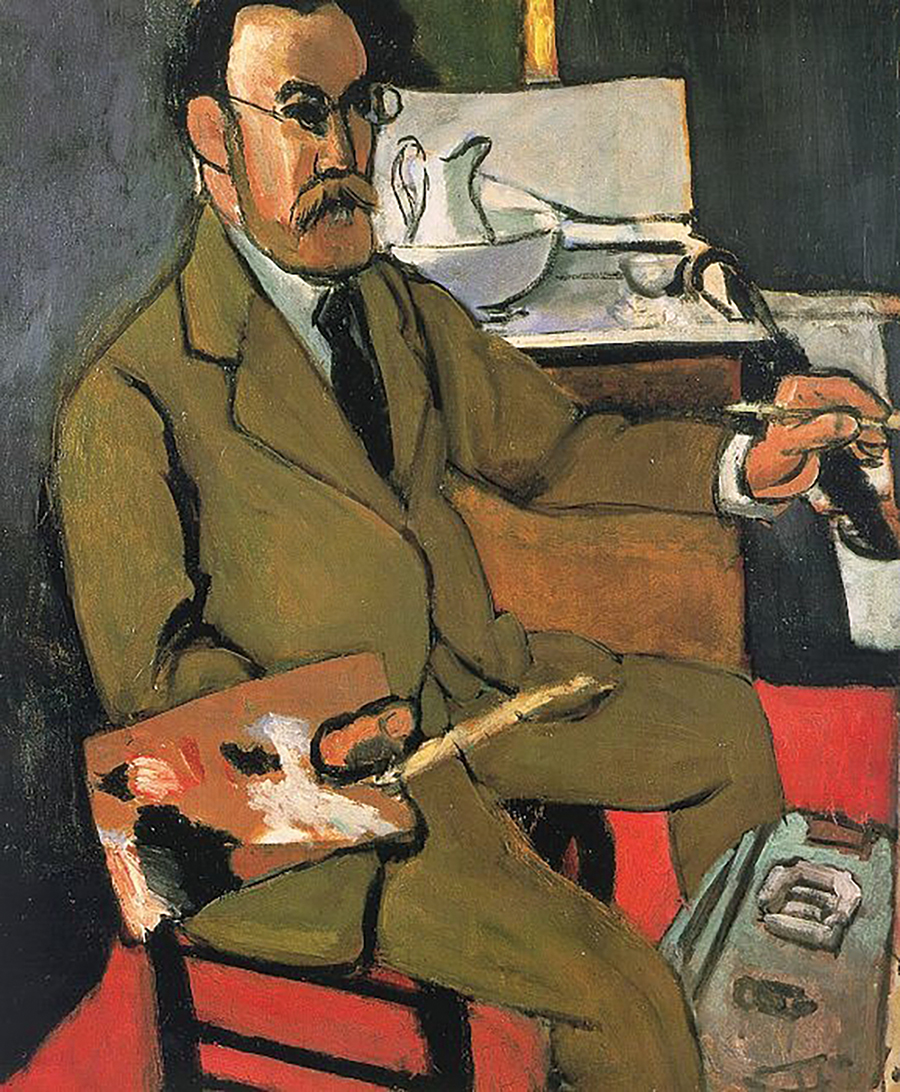

Coinciding with the N.C. Folk Festival, local artist Greg Hausler, owner of Wonky Star Studios, hosts a solo show at Greensboro’s Project Space, right next to Cincy’s Downtown, on September 5–9. “Color, Cloth & Chaos” features over 30 of Hausler’s works, which are far from traditional. In fact, Hauser suggests his style is a mashup of Marcel Duchamp, Jackson Pollock and Claude Monet with a little street art sprinkled in. “My paintings incorporate repurposed clothing that adds texture, depth and history to the canvas,” says Hausler. Look for everything from undergarments to socks and jeans. Push Play, which traveled to Belgrade, Serbia, for the 2022 Biannele Art Salon, features “a frozen heart that’s being reset.” To create it, Hausler used one of his old flannel shirts — peer closely and you will see the buttons — and a work glove, which has become the hand that’s about to press play. Of this piece, Hausler says that the heart represents “the place where all the inspiration has to go for it to come to fruition.” For more information, visit wonkystarstudios.com.

Sage Gardener

Okra is the Rodney Dangerfield of vegetables. Whenever I post about it on Facebook, some of my “friends” seem to think I’m urging them to partake of sizzling serpents au gratin. But no less an authority than Jessica Harris, author of High on the Hog, says it is “perhaps the best known and least understood” of Southern vegetables. I encourage you to read Harris’ account of how okra made its journey from Africa on slave ships to Southern “Big House” kitchens, where Black cooks introduced it into dishes such as turkey-neck soup. Since then, it’s become a chic addition in some of America’s hottest boîtes. Whether stewed in fiery New Orleans Creole gumbo or simply dredged in corn meal and fried, Southerners have been wolfing down okra for centuries. And why not? It is among the most heat- and drought-tolerant vegetables on the planet, even thriving in our Tar Heel red clay. Cultivated in the Middle East and India for millennia, the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians knew all about okra. The first mention of it in the New World was in 1619. Thomas Jefferson suggested snapping it from the plant rather than snipping it. My wife, Anne, cooks it to perfection, butter-frying the tiniest, just-picked pods in an a blistering-hot cast-iron pan.

So what’s not to like? “Okra is often spurned because of the gluey, even slimy texture it can present,” one food writer opines. C’mon. Let’s get it out there: Okra can be gooey, gloppy, gloopy, gummy and my favorite description, mucilaginous. But that’s only if you don’t have a clue about what you’re doing. Pick it small. And one British writer advises to treat it like the Mogwai in Gremlins films: “If you want it to stay cute, don’t get it wet.” Pat or brush it to remove dirt, just as you do with mushrooms. Cook it whole; frying it helps. “One way to de-slime okra is to cook it with an acidic food, such as tomatoes,” suggests one cook. And it’s good for you, lowering cholesterol and blood sugar levels, boosting your immune response and improving your gut health. Unless it doesn’t: “Okra contains fructans,” cautions another online source, saying okra can cause diarrhea, gas, cramping, bloating and a lingering onset of death — or maybe that was something else. Maybe my Northern friends are right; after all, okra is in the same family as cotton, hibiscus, musk mallow and even the notorious durian. But as you’re reading this, I very well might be whipping flour into a pan of smoking oil to make a roux à la Paul Prudhomme for some shrimp gumbo Ya-Ya.

And running through my mind will be a jingle from humorist Roy Blount: “You can have your strip pokra/ Give me a nice girl and a dish of okra.” — David Claude Bailey

Happy Trails

Just completed and opened by the Piedmont Land Conservancy in May, the main Caraway Forks Trail at Caraway Creek Preserve wanders through massive oaks and towering hickories to a historical artifact, a massive stone “check” dam dating back to the 19th century. Rather than forming an impoundment, check dams were built by farmers to slow down the flow of creeks and rivers during floods for silt retention and to protect their crops. Caraway Creek actually runs right under the dam to snake its way through shady bluffs and beetling ravines. Visit piedmontland.org.

Calling All O.Henry Essayists

Several years ago, readers responded enthusiastically to a contest challenging them to write an essay entitled “My Life in a Thousand Words.” Last year, we revived our challenge with a theme of “The Year That Changed Everything.” And this year, in honor of our namesake, who was known as one of America’s most popular — and highest-paid during his time — short story writers, we’re thrilled to announce that the 2023 O.Henry Essay Contest is all about “The Kindness of Strangers.”

We’ve all had a moment in our lives when someone we didn’t know stopped without hesitation to lend a hand.

When our family was new to a small, rural Maryland town, my daughter, Emmy, 4 at the time, took a dance class in a home basement studio up a bit on South Mountain, where we rarely saw human life, but did see bears. Unbeknownst to me, I’d accidentally left the overhead interior light on in my car when I parked, which became all too obvious when we left class at 8 p.m. on a cold, starlit October night. My husband, Chris, was out of town and there was no one I knew to call. I didn’t have any friends yet. A father of a fellow dancer saw my distress and drove us home. That was 12 years ago.

And now, we want to hear your story — whether you were on the receiving or giving end of that helping hand.

Of course, there are some rules:

- Submit no more than 1,000 words in conventional printed form. Essays over 1,000 will be shredded and used in our office hamster’s cage.

- Deadline to enter is December 24, 2023.

- Top three winners will be contacted via email and will be printed in a spring 2024 issue.

- Email entries to cassie@ohenrymag.com

We can’t wait to hear the clickety-clack of keyboards across the Triad as you write your stories — stories that are sure to remind us of all the goodness that exists in the world.

— By Cassie Bustamante, editor

Growing Goodwill

Survey four of the Triad’s youngest residents and one of them will tell you they face food insecurity. Share the Harvest board president Linda Anderson, a retired educator, does her best to improve that grim statistic. Sometimes, she says, it’s as simple as grabbing a hoe or driving a truck.

“There are times during the growing season when our gardens are overflowing with vegetables and we don’t know what to do with the excess. This is when Share the Harvest can help both the gardener and the individuals in need,” says Anderson.

Anderson says donations have grown since 2012 from a few community and church gardens donating food to local nonprofits into an expanding program benefitting organizations, collecting and distributing food to the needy via various programs offering meals and food pantries. For its 10 core volunteers, the need has motivated them to collect, coordinate and distribute donations from groceries, restaurants, gardens, farmers markets and even N.C. State A&T University’s farm.

From May through October, the growing season, they collect, aggregate, then store fresh products at a central collection site for distribution.

“In the beginning, the first year, we had 1,200 pounds of veggies. Last year it was 15,241 pounds received.” See sharetheharvestguilfordcounty.org for more information. — By Cynthia Adams

Muscadine season is here at last.

Muscadine season is here at last.