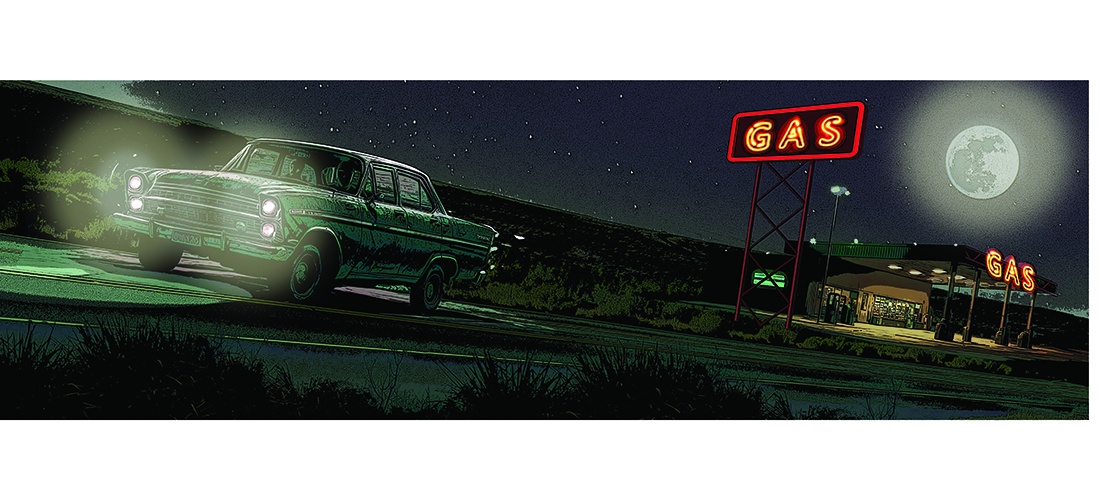

Fiction by Brendan Slocumb • Illustration by Mariano Santillan

He smelled like the cake factory: frosting, the yeasty stench of batter and butter, but more than anything else, sugar. Baked sugar, tangy and sweet, that coated the back of his tongue and the inside of his eyelashes. Leaving the factory at the end of the shift, he could feel the sugar aroma around him like a coat or a fog, always moving with him. Of course, his friends started calling him Bon Bon. He’d hated the nickname, but by now it had hung on him so long that he didn’t mind it.

He ordered another beer and checked his watch. His buddy, Tig, was late, as usual. Meet me at the bar at 6:30 and DONT BE LATE, Tig had texted him. SERIOUS!!!

Now it was 6:49, and he’d finished the first beer and ordered a second. Why Bon Bon had believed Tig that this time actually was urgent, Bon Bon didn’t know. He’d shown up in his work clothes without changing back into his street clothes, the King Arthur Brand cake flour misting up from his pant legs every time he shifted on the bar stool.

“You makin’ me hungry, buddy,” Alan, the bartender, told him for the third time. “What do you think of carrot cake? You a big fan?”

“I figured you for a chocolate cake man,” Bon Bon said. “That was your wife in the shop the other day, wasn’t it? She bought the 14-inch and the 18-inch. Double chocolate.”

“Wife loves them,” Alan said, buffing the bar and looking away. His A-shirt, with dozens of stains on it — bourbons, whiskeys, wines — barely covered his paunch. Seemed like Alan loved those chocolate cakes, too.

Bon Bon nodded politely, tried to squeeze out a smile and looked again at the door.

“You must get sick of cakes,” Alan said. “All them sweets. That vanilla confetti cake is my favorite.”

“Never touch the stuff,” Bon Bon said. “I only eat salty stuff. You got more of these?” He pushed the empty dish that had contained pretzels and peanuts towards Alan. The first few months at the factory, Bon Bon had eaten so many pastries that he became nauseated by the sight of anything with sugar in it.

He looked at the clock. It was 6:54. If Tig didn’t show by 7, Bon Bon was out of there. Home, out of the sugar-stenched clothes and into the shower. He imagined hot water sluicing over him, the powdered sugar circling the drain and disappearing. He fumbled in his pocket for his wallet, looking for a ten, when a familiar voice said behind him, “You stink like the inside of a fat woman’s purse, you know that?”

Tig. Of course. “What?” Bon Bon asked him. “What does the inside of someone’s purse smell like? And where were you?”

“They keep cake in them,” Tig said. “The ladies.”

“Nobody keeps cake in their purse,” Bon Bon told him. “That’s the dumbest thing I ever heard you say.” And he’d heard Tig say plenty of stupid things over the years.

“Come on, let’s go.” Tig was already heading toward the door.

“Go where?” Bon Bon said. “Why did you want to meet here? Now we’re leaving? What’s going on?” Bon Bon grabbed a handful of the peanut-pretzel snack from the newly replenished dish, thanked Alan with a wave and trotted to keep up with Tig, who was already outside

By the time Bon Bon caught up with Tig, he was almost to his car, a beat-up dark green Chevy Malibu, whose passenger door had gotten side-swiped years ago and was missing the side mirror and most of the chrome trim. Tig was what Bon Bon’s mother referred to as “a character.” Overalls, sleeveless shirt, dirt-and-oil-coated John Deere trucker cap, Reebok tennis shoes so faded and stained with oil and dirt that their color would forever be a mystery.

“Get in,” Tig said.

“Where are we going? When will we be back? I can’t just leave my car — ”

“GET IN,” Tig said, almost an order this time.

Bon Bon never knew why he got in the car that night. Maybe because he’d done other stupid things with Tig in the past and this was just par for the course. You wouldn’t believe what Tig just did, Bon Bon imagined texting his friends later tonight. It would be fodder for conversation for days to come.

The car stunk of cigarette smoke and chaw. A spit cup sloshed in the dashboard console. Bon Bon shoved McDonald’s wrappers, Entenmann’s boxes, Dunkin’ bags and miscellaneous trash off the seat, and got in. Before he could even buckle his seat belt, Tig spun the tires and headed out of the parking lot toward the highway.

“What’s this about?” Bon Bon repeated, swallowing the last of the pretzels.

Tig smiled. Drove for a minute, enjoying the power. Then, dramatically, he said, “I’m about to make us rich.”

“No,” Bon Bon said.

“Yep.”

“OK,” Bon Bon said. “Let me out. Turn around. Stop this piece-of-crap and let me out. I told you before. I’m not getting involved in any of your messed-up money-making — ”

“It’s guaranteed cash and you’re already in it,” Tig said without missing a beat.

“Stop the car. I mean it.”

“Too late. You’re going to thank me in about 12 hours.”

“What the hell are you talking about? Twelve hours? What did you do? What are we doing?”

“I just made you 23K. I get 27K, you get 23K.”

“For what?” Bon Bon asked. Frustration and fury boiled in his gut the way it often did when he had to deal with Tig. “You just handing me 23K for sitting here?”

“For coming with me, yeah,” Tig said, darting a glance at him. Bon Bon couldn’t decipher it. “All you gotta do is drive when I get sleepy.” The highway spooled out before them, the endless ripple of white lines bisecting the night. Few cars were out this late, and all seemed to be going in the other direction.

“Hell no. I don’t know what kind of craziness you’re getting into, but I’m out. I gotta work in the morning. Turn around. Take me back to my car.”

Tig laughed. “Bro, they won’t miss you at that cookie house. Besides, in 12 hours, you’ll have enough money to quit that job and do something that doesn’t leave you smelling like a giant cupcake. Lose that dumbass nickname. Grown man named Bon Bon. I’m doing you a favor.”

“Screw you. Dammit, I knew I should have just gone home.”

The car banked around a wide curve, then through a series of up-and-down humps in the road. If you drove fast enough, it was like riding a roller coaster. For an instant, you could lose your stomach as you crested the rise.

On the descent, a thump came from the trunk.

“What was that?” Bon Bon looked in the back seat, stacked neatly with big square boxes: Macbook Air, read several. UN3481, read others, with the logos of a battery and a flame. They were all laptop computers. The back-seat floor was the usual sea of fast-food wrappers, napkins and trash. Nothing moved.

The thump came again, as if whatever was back there shifted back to its original position.

“What’s going on?” Bon Bon asked. He couldn’t hide the note of nervousness now in his voice. “What’s in the back seat? Is that stuff stolen? You raid an Apple Store or something?” He tried to imagine how many laptops would be worth $50,000. There’d have to be at least twenty-five, maybe more.

“Nothing. Don’t worry about it.” The car was going faster now, well over 80 mph.

“I knew it. I freakin’ knew it. What did you do? I’m not dealing in stolen goods, Tig. Stop the car.”

Tig groped in the driver side door. Bon Bon thought at first that Tig was looking for his wallet or maybe a soda bottle. But after a moment Tig retrieved a small triangular object that seemed to absorb the dim lights from the dashboard before it resolved itself into a gun. It glittered as if alive. Tig gripped the handle and then the muzzle was pointing, impossibly, at Bon Bon himself.

“T, what the . . . ”

“Just shut up,” Tig said. “I’m doing you a favor. Nobody is getting hurt. We walk away with more money than either of us has ever seen.”

Bon Bon had only seen Tig this erratic once before. It ended with Carl Simmons walking with a permanent limp and Tig spending three years in prison for aggravated assault. Bon Bon stared at the dark muzzle of the gun. His mouth had gone dry, the pretzel crumbs turned to gooey dust on his tongue. He wiped his hands on his pants and could feel the flour and sugar coating his palms. He wanted to scream. Instead he took a deep breath, looked out the window into the dark, trying to ignore the feel of the gun staring at him. “OK man, just tell me where you got all these computers from. And what we’re going to do with them.”

“The less you know the better,” Tig told him. “Get some rest. You’ll take over in six hours. We gotta make the drop by 8 a.m.”

Bon Bon had heard that Tig had gotten into some shady business while he was in prison. This whole scenario was making more sense. Tig, and now Bon Bon, were driving stolen electronics over state lines. He wondered if $23,000 was worth getting caught. If the police pulled them over —

Tig turned on the radio with an aggressive punch of his forefinger. Kellie Pickler’s “Red High Heels” deafened them. Bon Bon turned down the volume.

Over the next two hours, Bon Bon sat in silence, thinking. Tig couldn’t be reasoned with, that was pretty clear. Bon Bon could wait till Tig fell asleep and turn the car around, but what would happen when Tig woke up? Bon Bon glanced down at the gun again, resting lazily on Tig’s thigh, and looked out the window. He could grab his phone and try putting it on mute and dialing 911, but the phone’s light would turn on and Tig would see it for sure. Bon Bon’s palms felt chalky from the mixture of sweat and cake flour dust. The damp, sugary smell from his trousers made him want to retch.

“Hey,” he said when lights from the next exit glimmered on the horizon. Signs for gas, food, lodging. “I didn’t get dinner when I was sitting there waiting for you, and I’m starving. Do we need gas?” He pretended to stretch and stifle a yawn.

Tig kept his eyes on the road, but his grip tightened for an instant on the gun, then relaxed again. “OK,” he said after a minute. “I am, too. All right. I’ll pump the gas and you get us some food.” Tig took the exit too fast, the car almost on the berm before he overcorrected. Again came the thump from the trunk. “And don’t try anything, man. I’d hate to kill you, you hear me?”

The gas station was a half-mile down the road, its fluorescent lights bright and disorienting. No cars were parked at the pumps. A single beat-up Honda sat tucked against the building. Bon Bon had been hoping for a late-night police cruiser, an RV, anything.

After the car had come to a halt, Bon Bon got out, making sure his movements were slow and casual. He could run in, tell the attendant to call the cops, who could be here in minutes. He glanced over at Tig, who was staring hard at him. He looked away, pulled open the glass door. He could feel Tig’s eyes on him, even in the snack aisle.

He picked up several bags of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, hot chili and roasted lime Takis, jalapeño Kettle potato chips, and honey barbecue and hot mustard pretzels. Then went to the refrigerators on the wall and pulled out four bottles of Pepsi.

At the cash register, Tig’s gaze brushed his shoulders as Bon Bon paid and the clerk stuffed everything in a plastic sack. Again and again, he contemplated saying something but then imagined Tig leveling the gun at them, the bullets spider-webbing the glass.

The door behind them jingled, and Bon Bon jumped. “You almost done, man?” Tig called in.

“Yeah,” Bon Bon said. The clerk put a handful of change on the counter, and Bon Bon swiped it into his palm. “You owe me 18 bucks,” he told Tig as he brushed past him out the door, out into the cool night and the waiting car.

“Oh you’ll get that and more soon, buddy.” Bon Bon could hear the relief in Tig’s voice. “You feel like driving now?”

“Yeah, I can take over,” Bon Bon said. “You eat up. Did you check on the trunk? On whatever fell over back there?”

“Don’t worry about it. It’s fine,” Tig said.

Bon Bon pulled out of the parking lot as Tig tore open the purple bag of Takis, stuffing a handful into his mouth. “Damn these are good. You want some?”

Bon Bon shook his head. “In a sec.” He took a sip of Pepsi.

“These things are spicy,” Tig said, playing on the word spicy. “Whooo-eee.” He cracked open his Pepsi and drained half of the bottle. Bon Bon took a sip of his.

Tig didn’t tell him where they were going, just directed him once to turn south, toward the highway running to the coast. Tig broke into the potato chips and Bon Bon munched on pretzels. They passed city after city, and a rest stop in three miles.

“I’m thirsty,” Tig said when he was halfway through the Honey Barbecue Pretzels. “These pretzels are making me thirsty.”

“Seinfeld,” Bon Bon told him without looking over. He checked the rearview mirror. The boxes sat primly on the backseat, giving away nothing.

“What?”

“Seinfeld,” Bon Bon said. “That was a running joke on Seinfeld.” The rest area illuminated the road. “Remember, George said it about 200 times during that show?” They passed the entrance, kept going.

“I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about. You got more to drink?” Tig said.

“There ain’t no more. We drank it all.”

“That ain’t funny,” Tig said. “I’m seriously thirsty. We gotta stop.”

“OK,” Bon Bon told him. “Next place we see. I need to take a piss, too,” he added.

They passed a sign. “Next Rest Area: 28 Miles.”

“Damn,” Bon Bon said. “Another half-hour.”

“We can make it,” Tig said, staring out at the darkness. But after another 10 minutes he said, “I really gotta go.”

“So do I,” Bon Bon said. “Bad. I’m going to pull over.”

He eased the Chevy onto the shoulder, put on his flashers. “What the hell you think you doin’?” Tig said, spraying pretzel crumbs onto Bon Bon’s shirt.

“What? You want me to piss myself in the driver’s seat? I didn’t shower after work because somebody wanted me to meet them at 6:30. So now I smell like cupcakes and if I piss myself I’ll smell a lot worse. That is not a good combination. So you’ve got a choice. Either stop yapping in my face and let me pee, or you can drive the rest of the way in a wet seat.”

He hoped Tig would be too preoccupied to suggest that he pee in the Pepsi bottle. Tig was.

“Whatever. Don’t do nothin’ stupid.” Tig got out of the car, slammed the door. Again the thump from the trunk, and then another.

The car’s headlights beamed into the nondescript grass as Bon Bon climbed out, went around the front of the car. As he reached the berm, he stumbled, tripped, and fell. Then got up, close now to Tig.

“Clumsy idiot,” Tig said, laughing, transferring the gun from his right hand to his left, unzipping. “Next rest stop we’re gonna get something to drink. I’m really thirsty. We got how many miles? 15 or — ”

Wham. The rock that Bon Bon had just picked up struck Tig perfectly, right on the temple. Tig dropped, soundless, so quickly that Bon Bon thought for a second that he was pretending.

But he wasn’t. A moment later he groaned, reaching for his scalp. Bon Bon lunged for the gun, grabbed it and sprinted back to the car.

In a moment, cinders flew and he was back on the highway, heart in his throat, going 70, 80, 90 miles an hour.

After a couple of miles he slowed slightly, pulse still pounding. The thump from the trunk came again. Bon Bon pulled over, popped the trunk, went around back.

Inside, a young boy lay wedged against tires and fabric, his hands and feet bound with zip ties. His eyes were bigger than any eyes Bon Bon had ever seen, with such terror and misery that Bon Bon couldn’t speak for a moment as he loosened the gag. The boy struggled away, a panicked bird.

“Hey, it’s OK,” Bon Bon said. “That piece of garbage can’t hurt you.”

He looked in the front seat for a knife, scissors, anything to cut the ties, but could find nothing. So he carried the boy to the front seat, tried to make him comfortable.

“I’m taking you to the police,” Bon Bon told him as he adjusted the seat belt. “The bad man won’t hurt you anymore, OK?” He tried to sound as calm and nonthreatening as he could.

“You smell like a cupcake,” he told Bon Bon accusingly, voice rough.

Bon Bon laughed. “Story of my life,” he said. “I get that a lot.”

The little boy eyed the bag of pretzels, tucked in between the seats. “Can I have some?”

Bon Bon reached past him for the pretzels, fed him a couple at a time.

“These are making me thirsty, “ he said.”

“Do you like Seinfeld, kid?” Bon Bon said as he pulled out his phone and dialed 911. OH

Brendan Nicholaus Slocumb is a graduate of UNC Greensboro with a degree in music education. He is the author of The Violin Conspiracy and Symphony of Secrets. He is currently working on his third novel.