A groovy roll in the hay with some guys and dolls on the outskirts of town

This is not the story of a place, but a snapshot from a bygone era, when a madcap company of young, stage-hungry performers were tossed into a singing and dancing whirlwind of entertainment that blossomed into lifelong friendships and happily-ever-after romances.

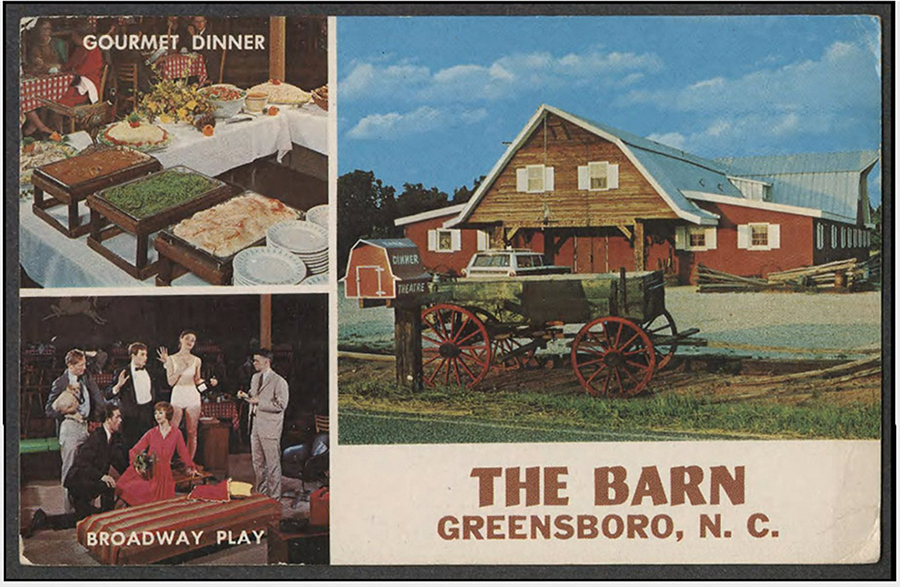

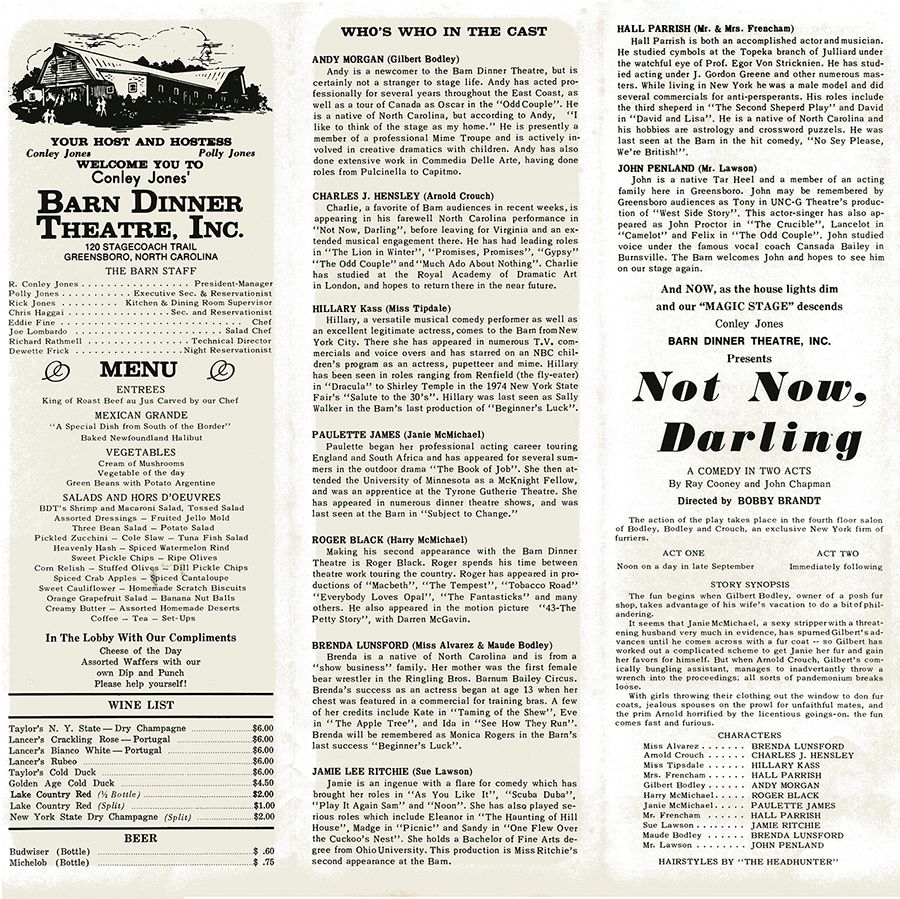

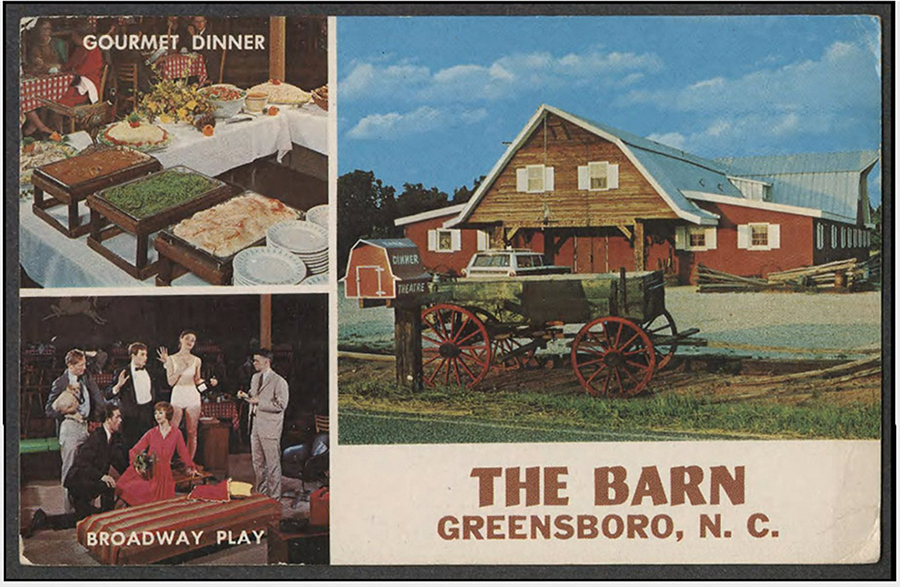

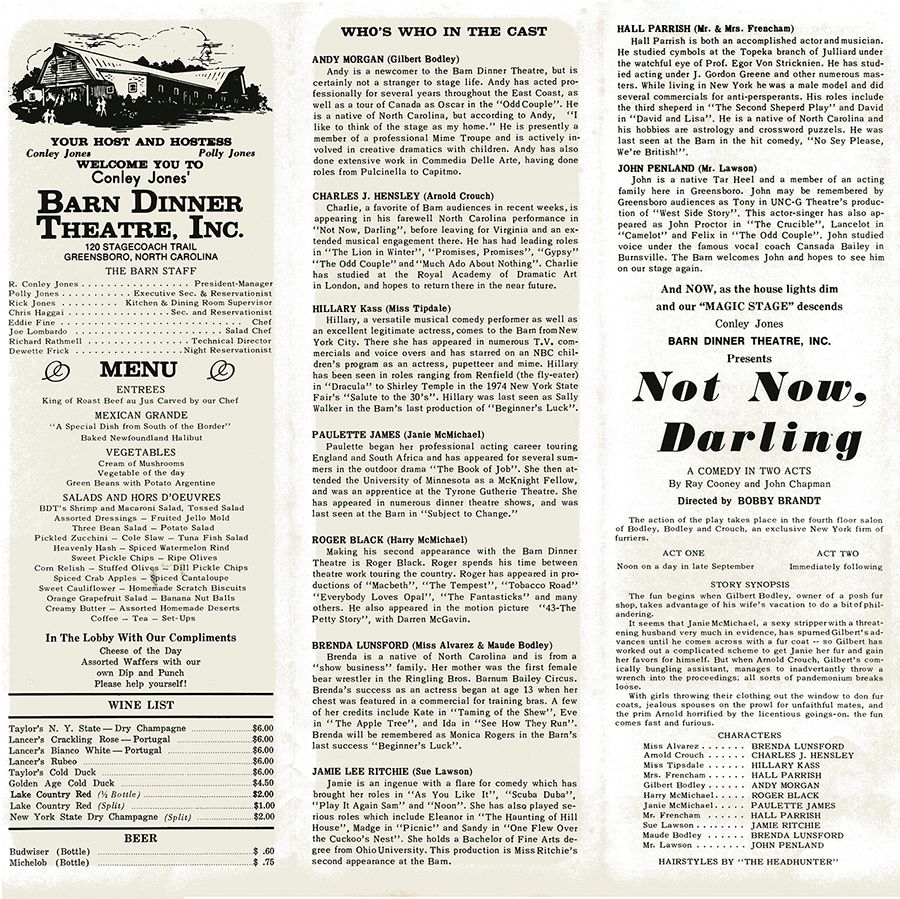

The Barn Dinner Theatre on Stage Coach Trail, the oldest continuously running dinner theater in America, has treated our community to remarkable performances for almost 60 years now, providing an outlet for creative expression by artists who have inspired generations of actors and directors.

The very first Barn Dinner Theatre was established in Roanoke, Va., in 1964 by Howard Wolfe, followed quickly that same year by The Barn in Greensboro. Within a short span, 27 Barn Dinner Theatres spread out across the country, concentrated mostly in the South. Wolfe’s insurance underwriter, Conley Jones Sr., took notice of how phenomenally successful this “play with your food” dinnertainment concept was. Conley, who died in 2015, ultimately purchased The Barn in Greensboro.

Productions were cast and produced by J. G. Greene in New York City, then directed in Roanoke before making their way to Greensboro, on to Atlanta, down to Marietta in Florida, and out to the other Barns. As soon as one show moved on, another was positioned to hit the ground running.

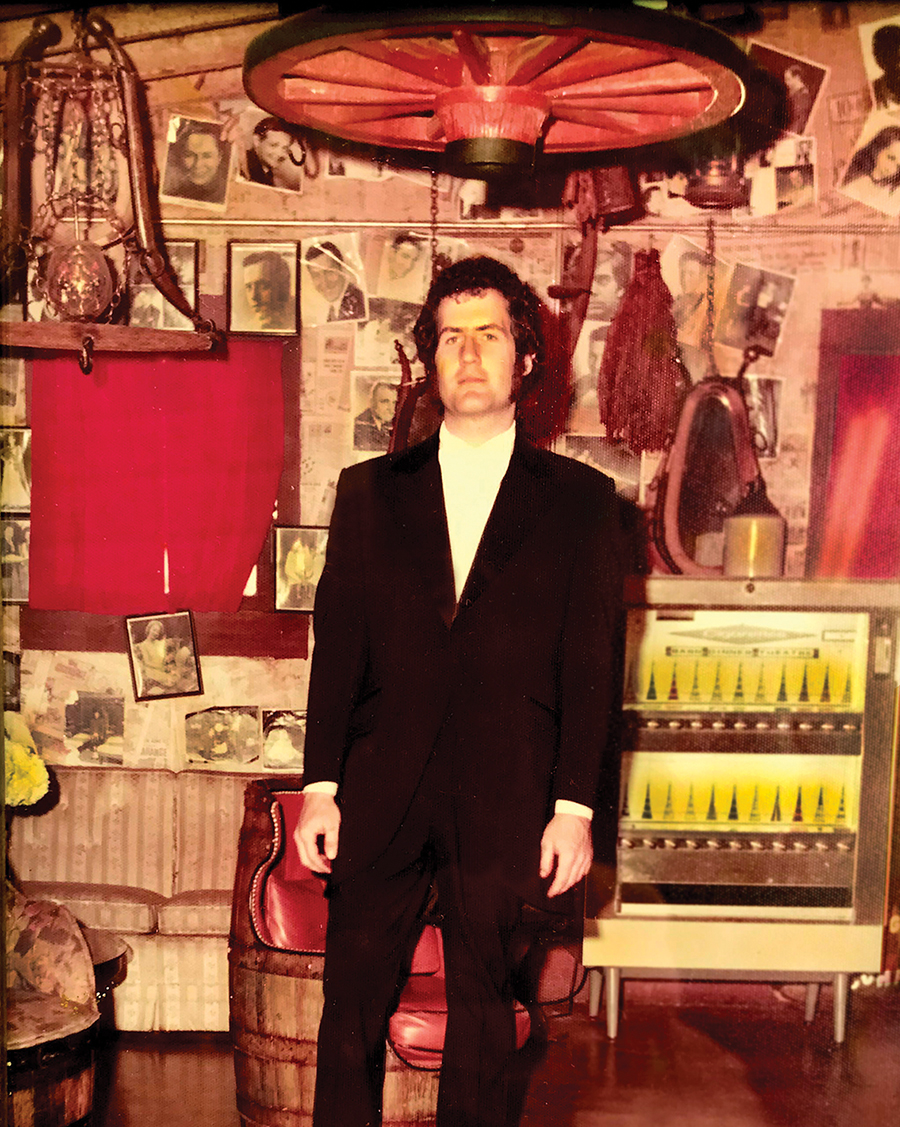

Advertisements touted the fact that “New York actors” were staging Broadway quality shows. Performers were guaranteed a six-month run with dinner and a free room on the premises. Stars who came through town in the 1960s included a young Fannie Flagg, Robert Blake and Mickey Rooney, but most of the working actors were unknowns.

After an all-you-can-eat buffet, the “Magic Stage” with actors and props in place descended from above via hydraulic motors. Within a minute the show was underway.

“I got called in by [UNCG theater department head] Herman Middleton,” actor Bobby Bodford says of his introduction to The Barn in 1969. “He said that the Barn Dinner Theatre had lost an actor and was looking for a young male that could learn lines quickly. This was early afternoon and I had to go on that night.”

Bodford was told by Conley Jones that his salary would be $50 a week plus tips, “And I said, ‘Tips for what?’ And he said, ‘You’ll wait tables up until about 20 minutes before the show.’” This was the era of brown bagging, and, in North Carolina, no alcoholic drinks were served. Customers brought their own booze and ordered whatever they wanted to mix it with.

At the end of each performance the actors would line up near the exit where customers had to walk past them. “I didn’t want to do it,” Bodford recalls. “The New York actors told me, ‘No, you definitely want to do this. You watch, they’ll shake your hand and remember you waited on them, run back to the table and put down a few bucks.’” One summer Bodford bought a motor home just from his gratuities. Not long after, professional waiters were hired and actors started making more than $50 a week.

Around 1969, some of the theater owners in the chain decided it would be more cost effective to hire their own actors and produce plays themselves. “They would refuse to pay the franchise fees,” Bodford says. Eventually a court ruled that theater owners could do as they please, even use The Barn name. “Once they figured that out, theaters started cropping up everywhere,” Bodford says. The Barn Dinner Theatre here switched over to locally produced productions as well. Still, almost every night the house was sold out.

Barry Bell was studying drama at UNCG when he first became associated with The Barn. “We weren’t supposed to work out there or do theater anywhere but school, but I did anyway,” he says. “The first couple of shows I did there were in 1969, so I missed Robert De Niro by two years.”

Did De Niro actually appear at The Barn? “My cousin, Michael Lilly, was wardrobe on Raging Bull,” Bell says. “De Niro told him, yeah, he was there. As the lead in a play called Tchin-Tchin, this was one of the budding actor’s first paid gigs, receiving $80 a week for a performance described as, “heart-warming” and “a delightful escape into romantic comedy.” De Niro was quoted as saying he enjoyed his experience in Greensboro, but Conley Jones circulated a rumor that the 23-year-old actor was fired because he refused to wait tables.

“Somebody was supposed to direct a show and didn’t come down,” Bobby Bodford says about transitioning from actor to director. “It was one of those things like, well, somebody’s gotta do it. Once I started directing, I really didn’t want to act anymore.” Not having to hang around for the monthlong run of the play, “I could open up a show here, then go to Tennessee and open a show there. I really enjoyed that more.”

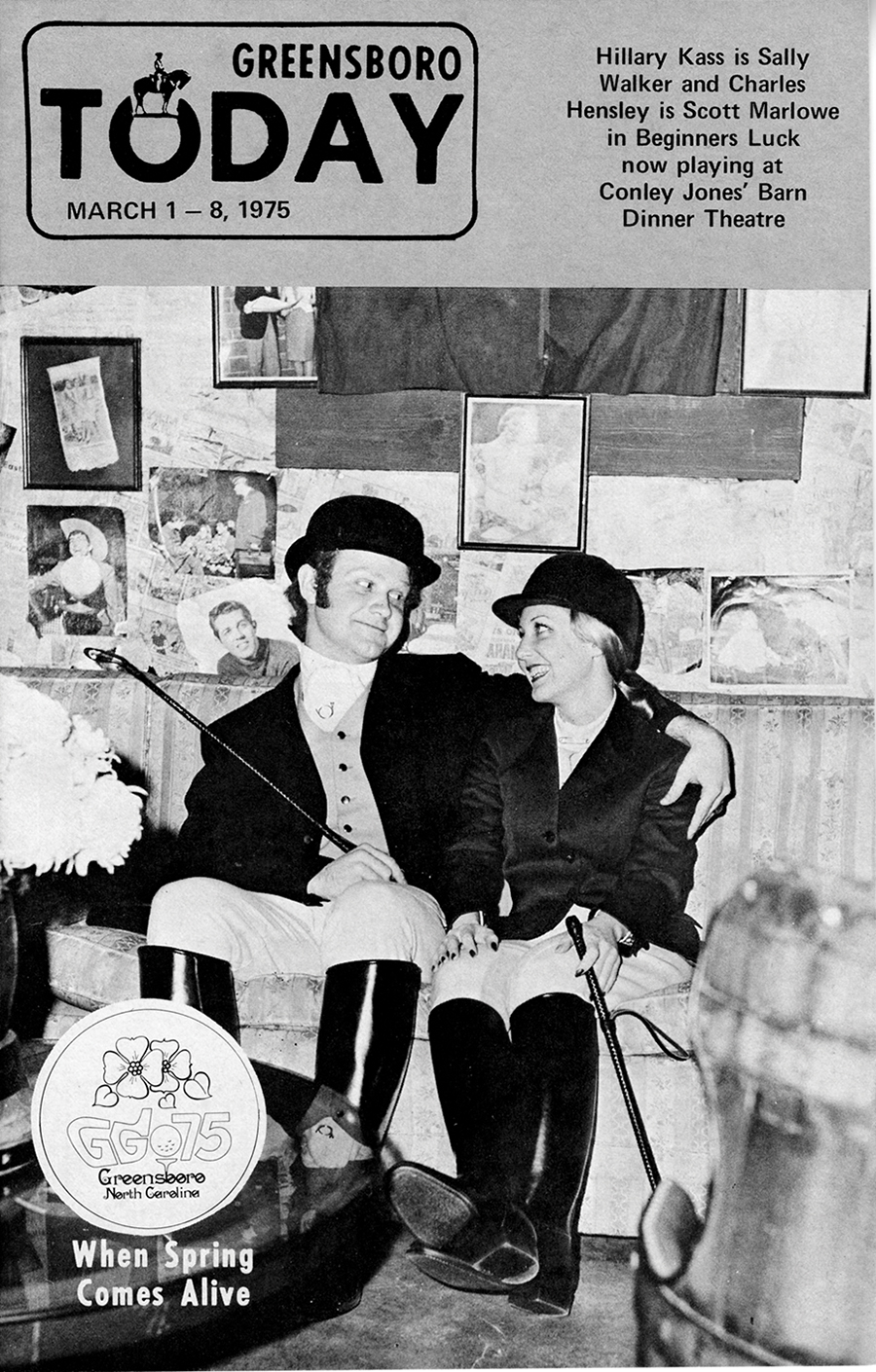

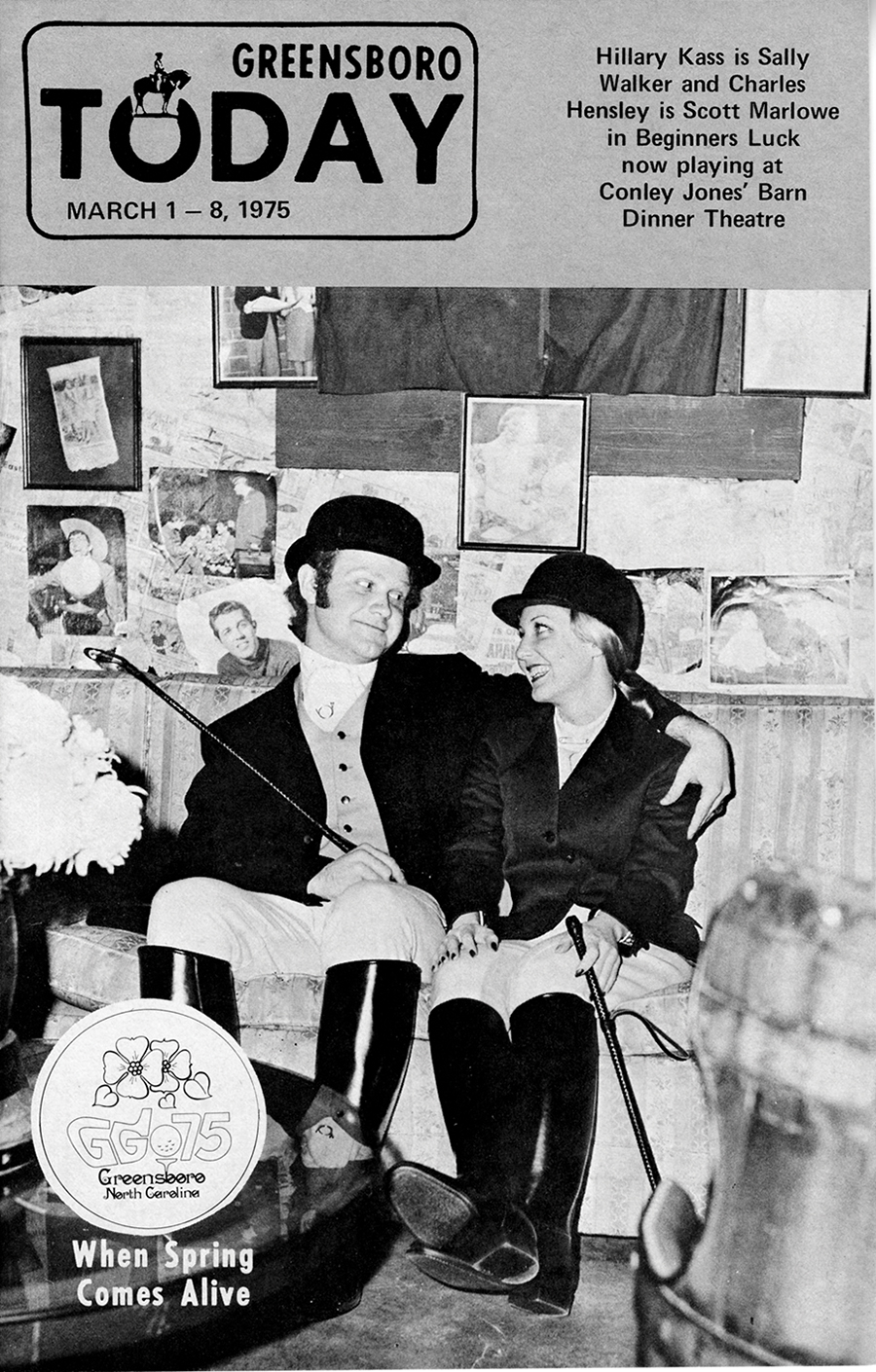

James (Jimmy) Fisher was in graduate studies at UNCG in 1974 when Bodford cast him in one of his shows. “It was a play called Beginner’s Luck,” Fisher recalls. “The first play I directed was called Spinoff. Neither of them are great dramatic works. They were the kind of sitcom things that were very typical in those days.”

“It’s a funny thing about the theater,” Fisher says. “Because you really do build relationships very, very quickly — relationships that you remember the rest of your life. And sometimes you never see those people again, you know?” Bodford was directing Fisher in a production of Annie Get Your Gun starring an actress from New York, Dana Warner. “After a considerable effort on my part,” Fisher says, “she finally went out with me. And we’ve been married for almost 46 years.”

Katina Vassiliou Madison had been appearing in productions at Page High School and with Livestock Players in the early ’70s. As an undergrad at UNCG she made her debut at The Barn. “I jumped at the opportunity,” Madison tells me. “You rehearsed all day for two weeks and then boom, you had to be ready to perform two matinees and performances every night. Your energy had to always stay up.” Madison accepted a day-time position in the reservation office. When not onstage, she served wine and beer in the lobby. “I’d be stage manager, whatever job they had open,” she says. When an actor’s zipper ripped open on stage it fell on Madison to stitch it up: “I had to get down on my hands and knees to sew up his fly in the lobby,” she says. “You can imagine how funny that looked. I can vividly remember thinking, ‘Please God, don’t let anybody go to the restroom at this moment.’” Naturally there were mishaps and mischief galore this is the theater after all.

“A rat fell out of the vent one time into somebody’s plate,” Bodford recalls. “Conley came over and said, ‘I am not gonna charge you for that. You got something extra special for free.’ Seriously, and then he just left.”

“Brenda Lilly was playing a Cockney maid,” says Mina Penland recalling an onstage prank. “An actor named Randy Ball packed his suitcase with bricks and she’s supposed to go off the stage with it but she couldn’t lift it. So she ad-libbed for 10 minutes and the audience loved it.”

“In Last of the Red Hot Lovers, there’s a scene where Barry Bell’s character has to roll a joint,” Bodford recalls. “Barry said, ‘I’ve been told if you take Lipton tea and roll it up, it kind of has the same smell.” After a few performances smoking that tea, “We’re sitting in the green room when two detectives come in and want to go through our props because somebody said they’re smoking marijuana on the stage at The Barn Dinner Theater.”

It’s a distinct, irreplicable, zen-like experience when everything clicks, audiences and actors become like one, momentarily inhabiting a world entirely unto themselves. After the final bow, it takes hours to decompress from a peculiar form of exhilarating exhaustion. “We had lots of wild parties running around in the field behind the Barn, butt-naked, drunk . . . ” Bodford says. “That’s something you probably shouldn’t write.” Oops!

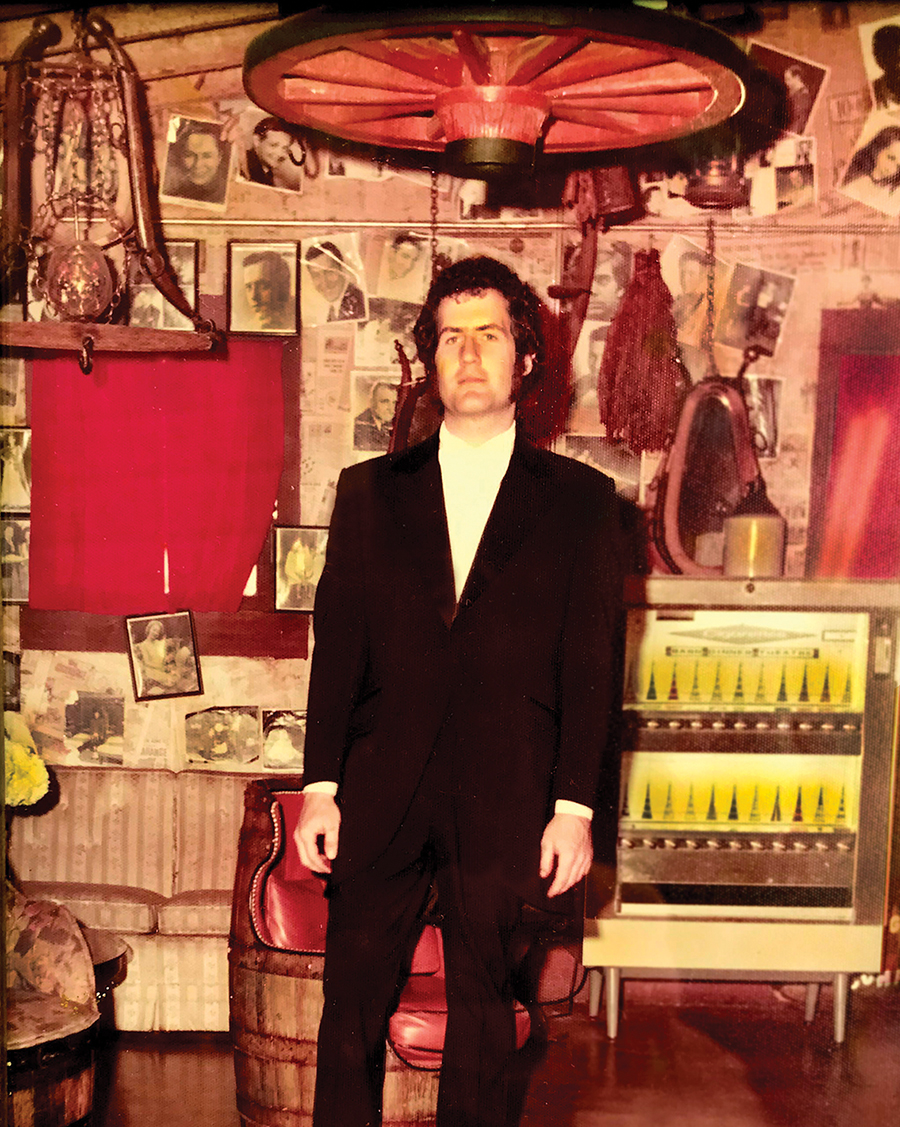

Conley Jones was, by all accounts, a colorful character who wore pistols in a holster on his hips, parading around like the caricature of a Southern sheriff — the sort of person who had people continually thinking, “I can’t believe you just said that out loud.” He considered actors a necessary evil. “He didn’t understand that we were the reason he was there,” Bodford says. With “no love for theater and no knowledge of how it worked,” Jones would refer to the players as “them goddamn actors.”

The performers’ quarters upstairs could house around eight people. An intercom system allowed them to monitor the show going on downstairs. “This big actor named Steve accidentally walked into Conley’s office one night and he was listening into our rooms,” Bodford recalls. “Steve was so upset the next morning he got a screwdriver and disabled every single one of them. And Conley never said a word about it.”

Barry Bell returned from working in New York to run The Barn from 1981 until 1992. “I did Fiddler on the Roof three times,” he says. “Fiddler and Oklahoma were licenses to print money. We normally ran straight plays about four-and-a-half weeks and musicals about six. I think Oklahoma ran like 16 weeks.”

The most difficult aspect of Bell’s tenure was dealing with The Barn’s owner, who could, at times, engage in shady practices. “Conley Jones finally got caught and burnt by the IRS,” Bell recalls. “I got a check for almost $7,000 and the waiters were getting checks for 3,500 bucks.” On the other hand, Bell says, “If a show sold really well, Conley would come up to me the next morning and say ‘Thank you Barry, thank you a lot,’ and stick $600 in my pocket.”

Barry Bell insists the buffet was good for what it was. “They always had that huge steamship round of beef. And the giant halibut, some of them 150, 160 pounds that were five feet long. A lot of people loved that fish, but, to this day, I can’t eat halibut or roast beef.”

Lorrie Lindberg, who was in grad school at UNCG in the early ’80s when she began working at The Barn, recalls “I did A Couple of White Chicks Sitting Around Talking and Cat On a Hot Tin Roof.” Lindberg worked at a few out-of-town venues after she graduated. “When I came back to Greensboro, I had been told by tons of people that I needed to meet Barry Bell, but we never were in The Barn at the same time.” Bell would be in New York when Lindberg was at The Barn or vice versa. “Everybody that had told us that we needed to meet each other were all standing in the lobby at The Barn because I was dropping off a friend of mine who was doing The Mousetrap. They were all in that show that Barry was directing. So they all saw us meet in the lobby at the Barn.” That was 1983, “We started living together maybe a week after that and we’ve been together ever since.”

As one of several Barners who moved to Los Angeles to pursue a career, Bobby Bodford eventually found himself working as Angela Lansbury’s costumer on Murder She Wrote. “She liked what I did and she liked working with me,” he says of the legendary actress. “But she was always saying, ‘Go back to the theater.’” Bodford had fallen in love on the courthouse steps of the Back to the Future set and was now married. “I never understood why the heck I was in Los Angeles.” Wanting children but having no desire to raise them in the City of Anything but Angels, in 1992, “We decided we were going to move back to Greensboro and Angela was delighted to hear it.”

Barry Bell severed his ties with the theater in 1992. That’s when, on the road to Greensboro, Bobby Bodford received a most unexpected phone call. “Conley Jones heard that I’m coming back and he says, ‘I’ve got people here that say you would never direct another play for me.’ I went, ‘Oh, no, I will! I don’t have a job,” he recalls. It felt something like home and Bodford spent the rest of the ’90s as The Barn’s creative director. “It was more sophisticated than it had been previously. It was a big deal. I think even then it was six or eight bucks for dinner and a show.”

Lots of young actors who cut their teeth at The Barn went on to bigger things. “Beth Leavel, who just won a Tony a couple of years ago, worked at The Barn a bunch,” Bell says. Lillias White achieved stardom after wowing audiences in Barn presentations of Love Machine and The Color Purple. Nominated twice for a Tony Award, White brought it home in 1997 for Best Featured Actress in a Musical. Winning both an Obie and Drama Desk Awards for her musicality, she’s well-known to youngsters as the voice Calliope in the Disney flick Hercules.

When Conley Jones passed away in 2015, Ric Gutierrez had been manager and producer at The Barn for two decades. Barry Bell and Lorrie Lindberg moved to Richmond, where they both taught at Virginia Commonwealth University. He has since retired. Bobby Bodford still directs theater productions in the area. “My wife Nicole became a member of our theatre family the minute my friends met her. I’m no longer Bobby — it’s Bobby and Nicole,” he says.

“I ended up teaching in Indiana for 29 years,” James Fisher says of his post-Barn days. “My wife, Dana, and I talked all the time about retiring in Greensboro. UNCG was looking for a department head and got in touch with me about the possibility of applying.” Fisher served as head of the theater department at UNCG from 2007 until he retired in 2019, winning multiple awards for excellence and authoring several books.

“It’s all interwoven,” Fisher says upon reflection. “Barry Bell, Billy Wagner, Bill Rollerson, Jan Powell, Charlie Hensley, Michael and Brenda Lilly, on and on. These are people who have come in and out of our lives over what is now getting close to 50 years. We always talk about getting together and doing one more show. I doubt it’ll ever happen, but it’s fun to think about.” OH

An abundance of thanks to Barn alumnus Charlie Hensley who provided connections to these esteemed performers and educators, allowing this humble scribbler to witness from the wings a magical moment of theater history.

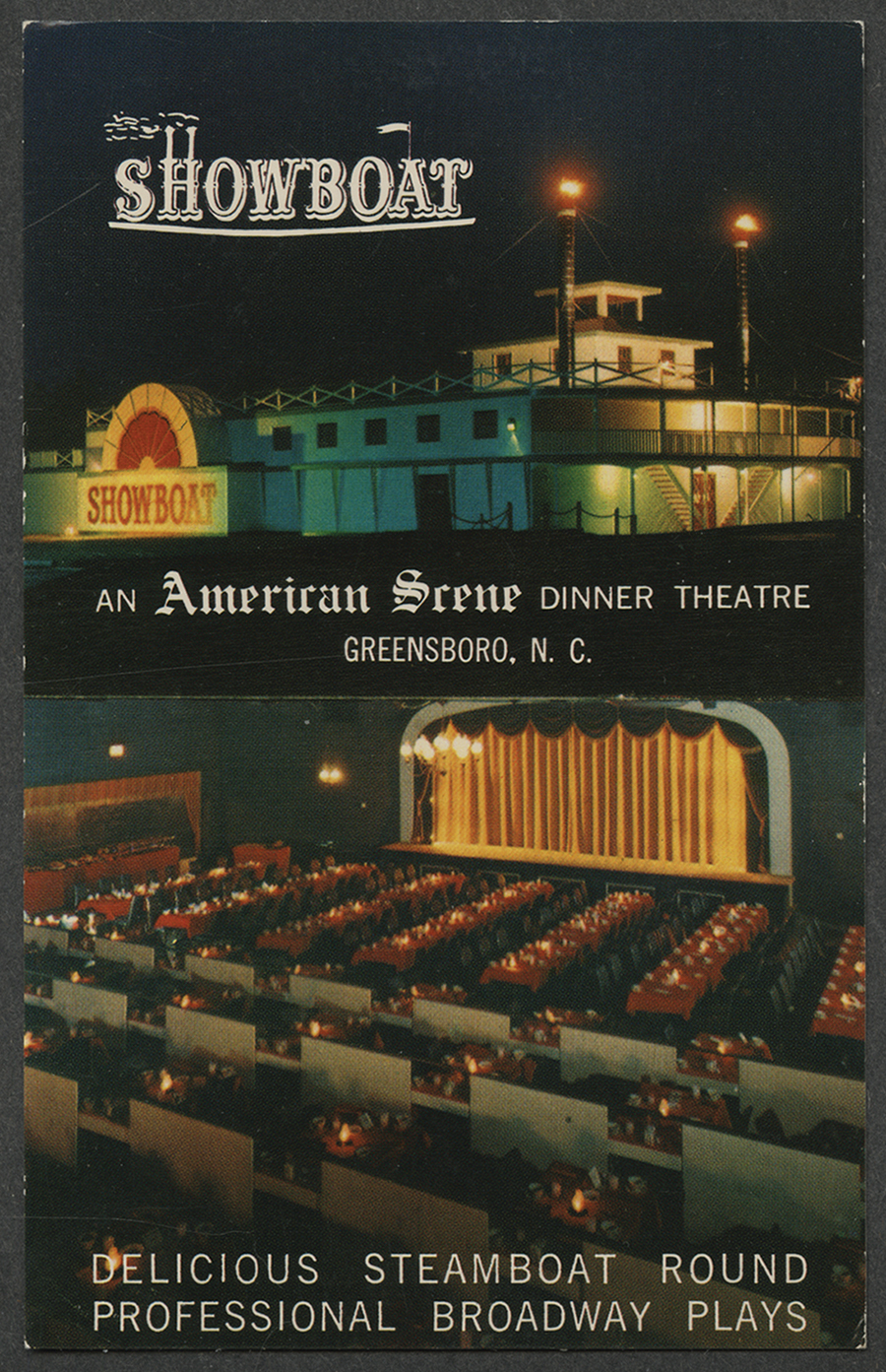

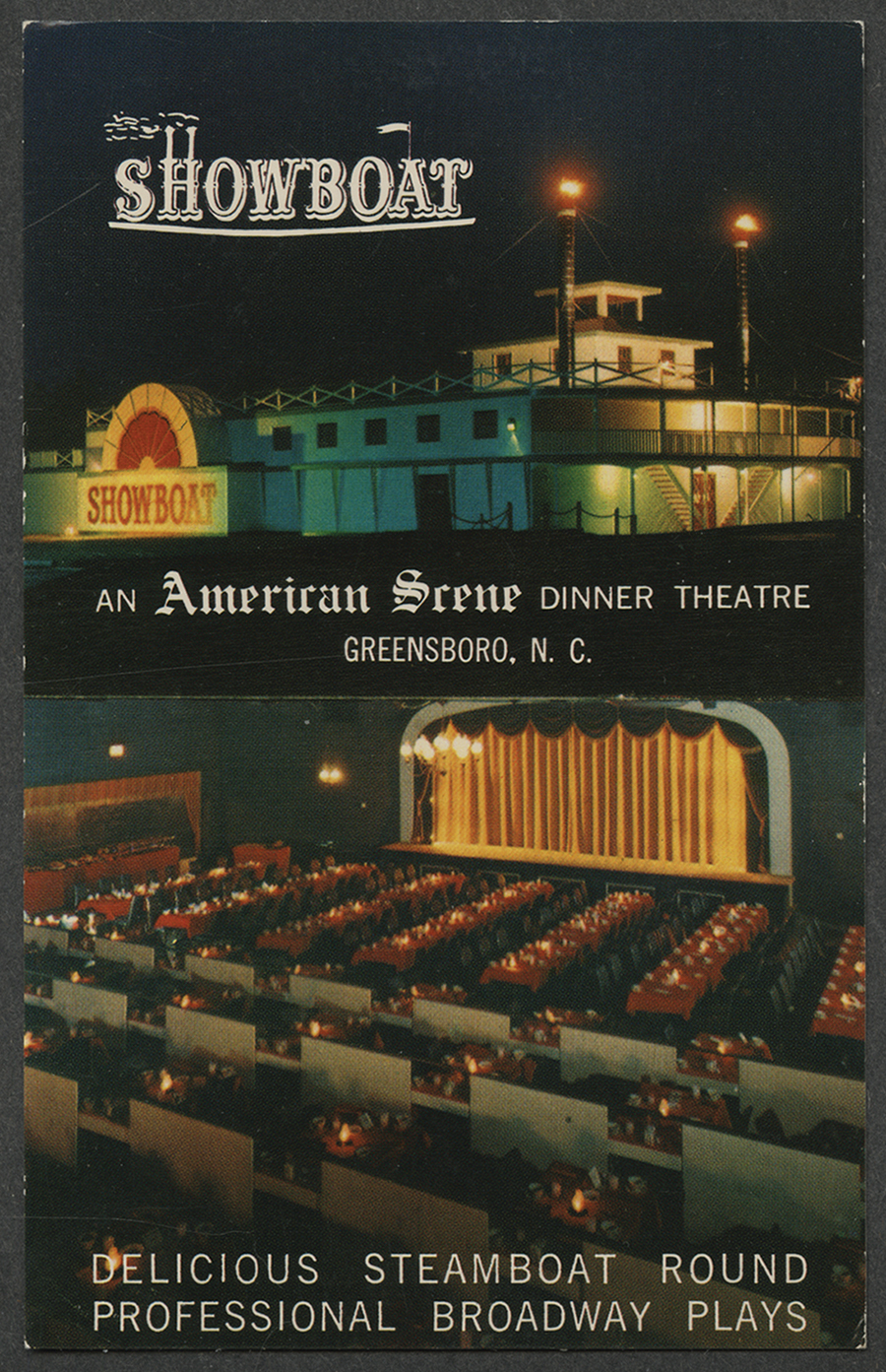

Showboat Dinner Theater

In 1965, Showboat Dinner Theater, An American Scene Dinner Theatre, opened off N.C. Highway 68 on Gallimore Dairy Road in a building resembling a New Orleans riverboat. Patrons crossed a bridge over a man-made lagoon to traverse from the parking lot to the theater. Just about every night, Conley Jones would corral an employee to drive him over to the Showboat to count the cars in the parking lot.

“The Showboat used, if I’m not mistaken, union Equity actors,” Barry Bell notes. “And Conley, at The Barn, didn’t. He didn’t even pay the actors to rehearse the new play.” There’s a legendary story about what happened when Actor’s Equity came down from New York to organize a protest. “If you look at the front of The Barn, there are two windows up in the peak,” Bell says. “Conley’s desk was right there by that window and he threw M-80 fireworks out the window at them.” One of the trade papers sported a headline that read something like, “North Carolina Theater Producer Fires on Equity Protestors.”

Around 1969, budding actress Mina Penland was in rehearsals for I Do, I Do, directed by Bobby Bodford at the Showboat Dinner Theatre, which had opened four years earlier. That production never made it before an audience due to someone in management absconding with the funds, leading to the theatre closing. She ended up doing plays at The Barn and her brother Dodie Penland became the Barn’s stage manager, who greeted the audience as it arrived.

Showboat went under after just a few years and became Jung’s Galley, the new location for Jung’s Chinese restaurant, formerly located in a Tudor inspired mansion on Church Street, close to Summit Avenue. In 1977, the site became Bill Griffin’s Boondocks nightclub for a time. OH

Wednesday Night Blues Jam at Ritchy’s Uptown Restaurant and Bar is fast becoming the place to be. Hosted by Shiela Klinefelter, an accomplished bass player and vocalist with Shiela’s Traveling Circus, and Chuck Cotton, it’s a great night of raucous melodies sure to get your feet moving.

Wednesday Night Blues Jam at Ritchy’s Uptown Restaurant and Bar is fast becoming the place to be. Hosted by Shiela Klinefelter, an accomplished bass player and vocalist with Shiela’s Traveling Circus, and Chuck Cotton, it’s a great night of raucous melodies sure to get your feet moving.

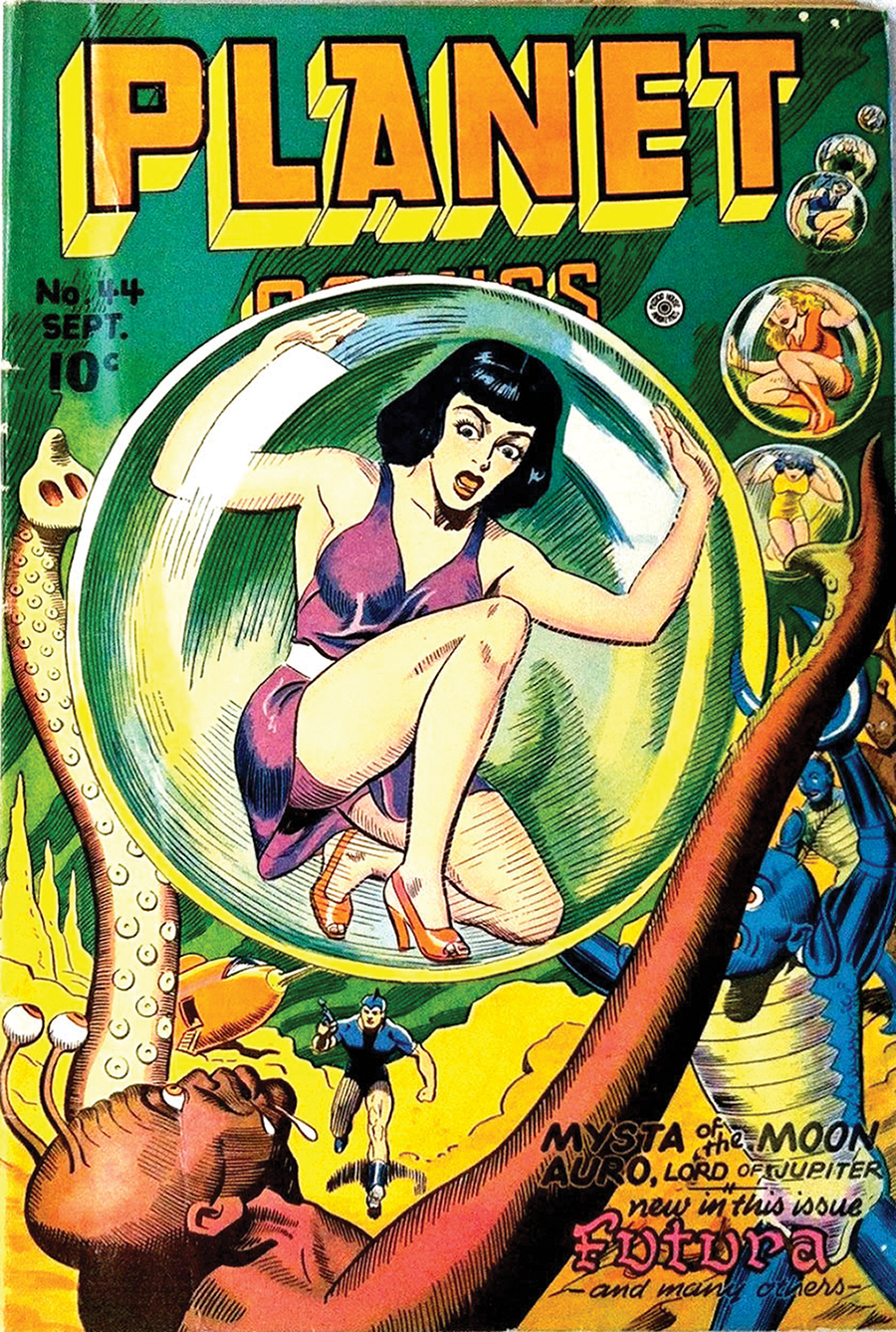

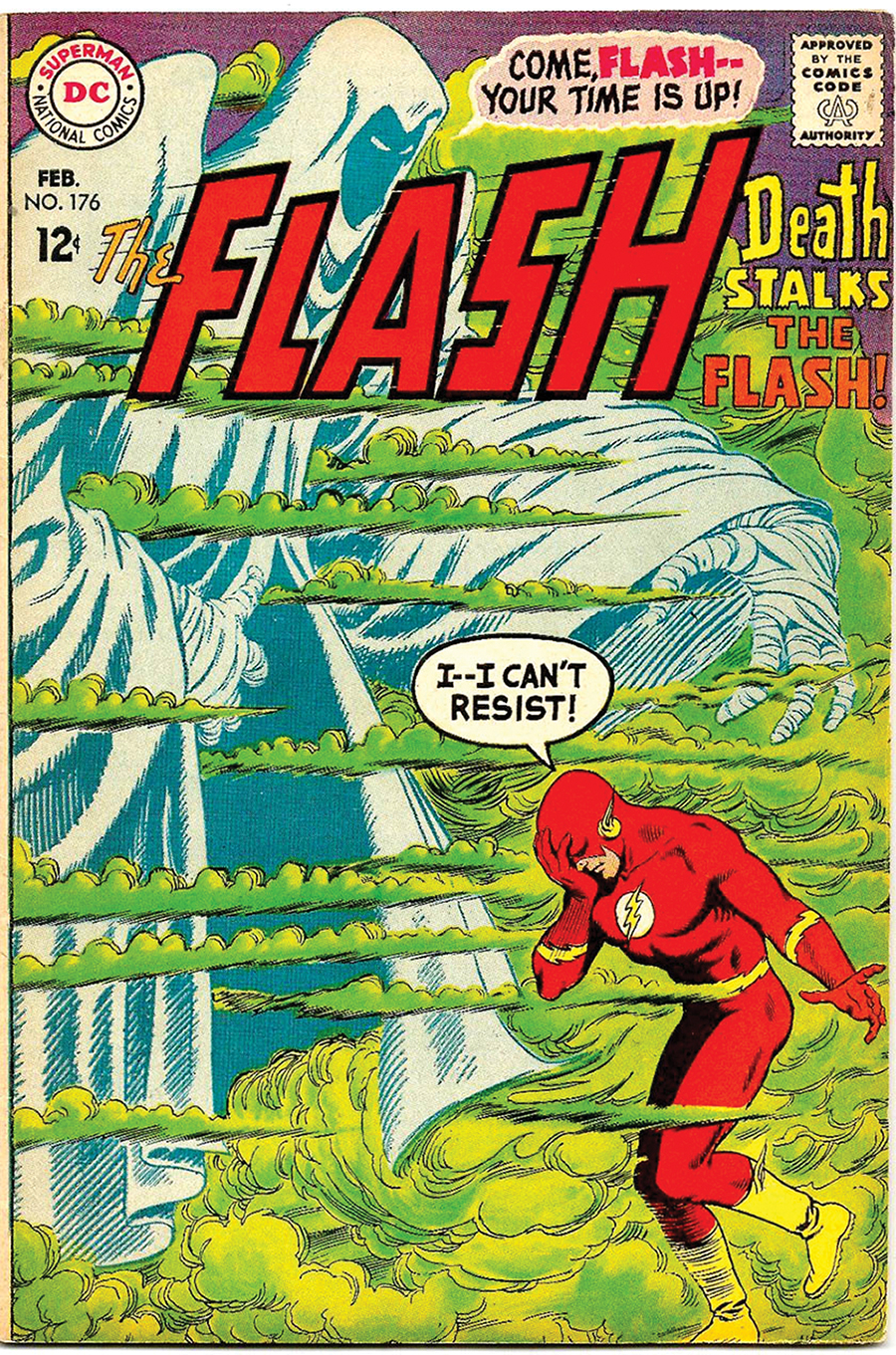

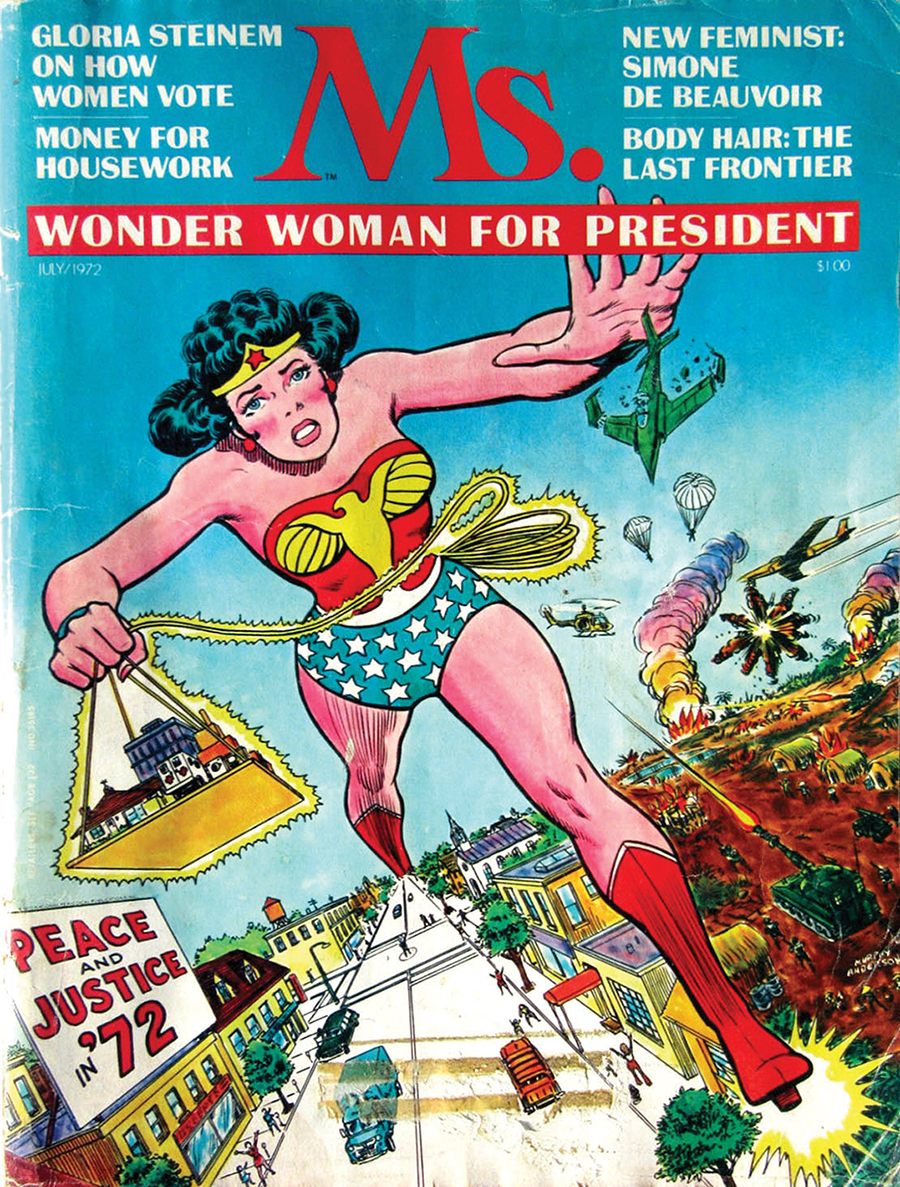

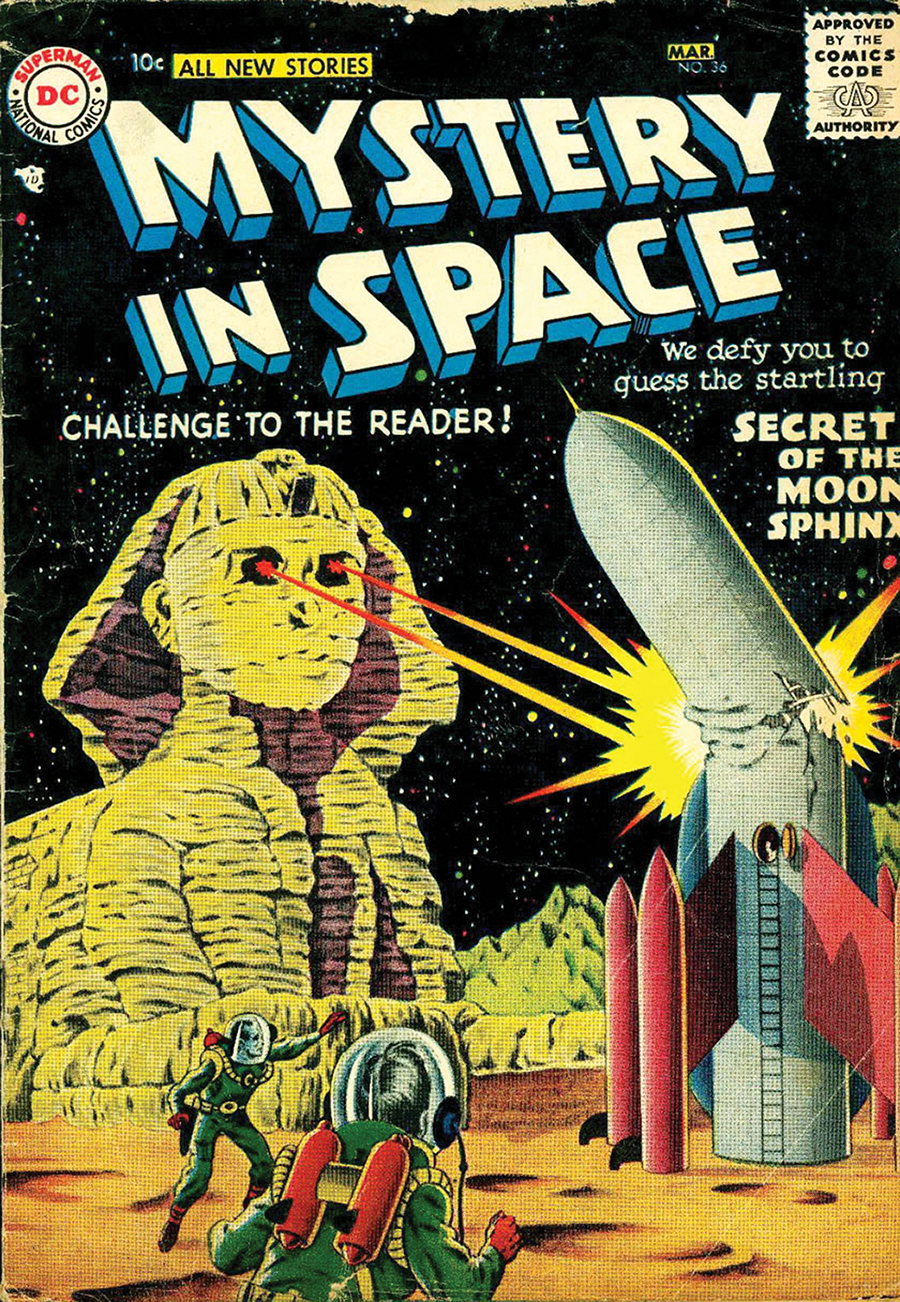

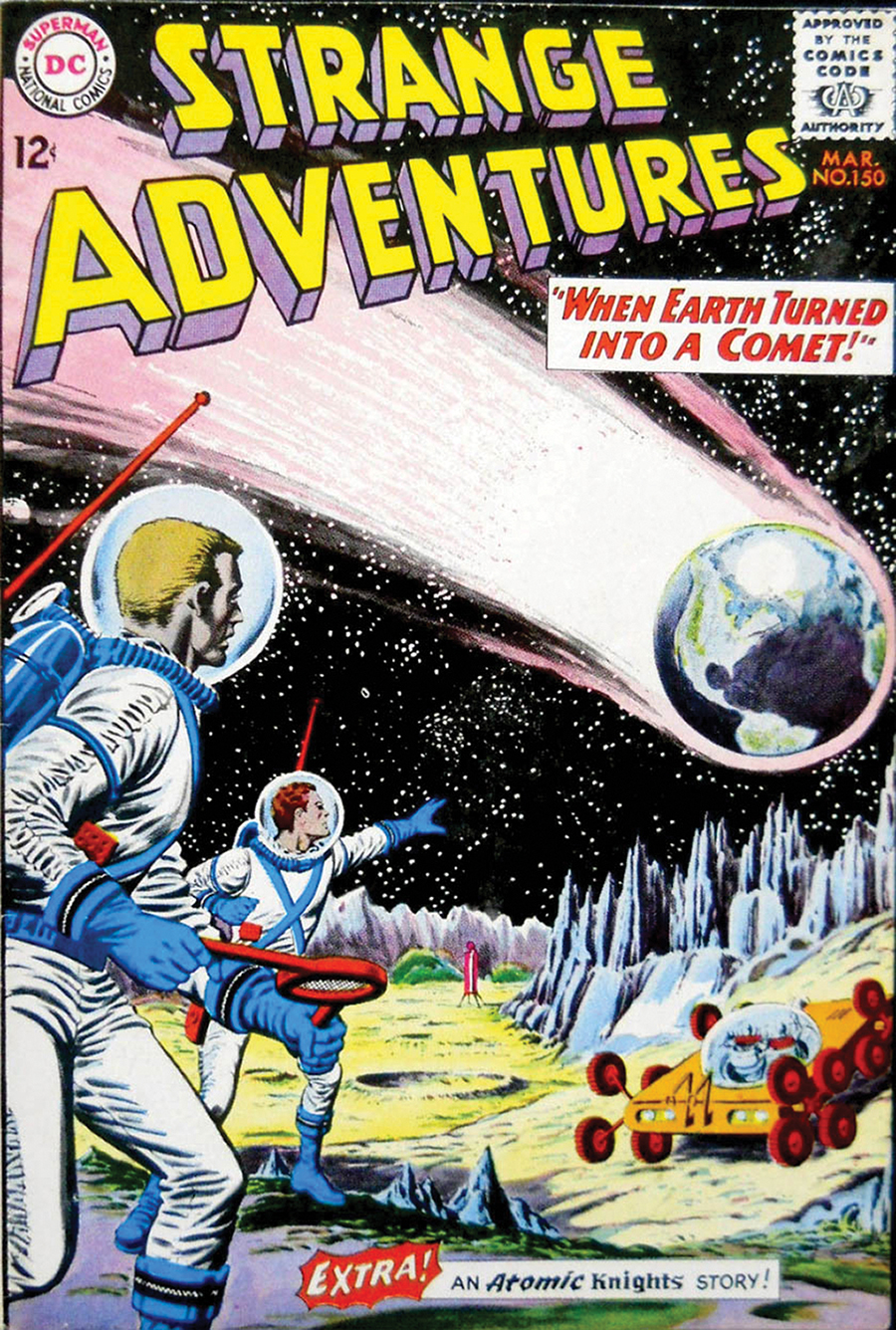

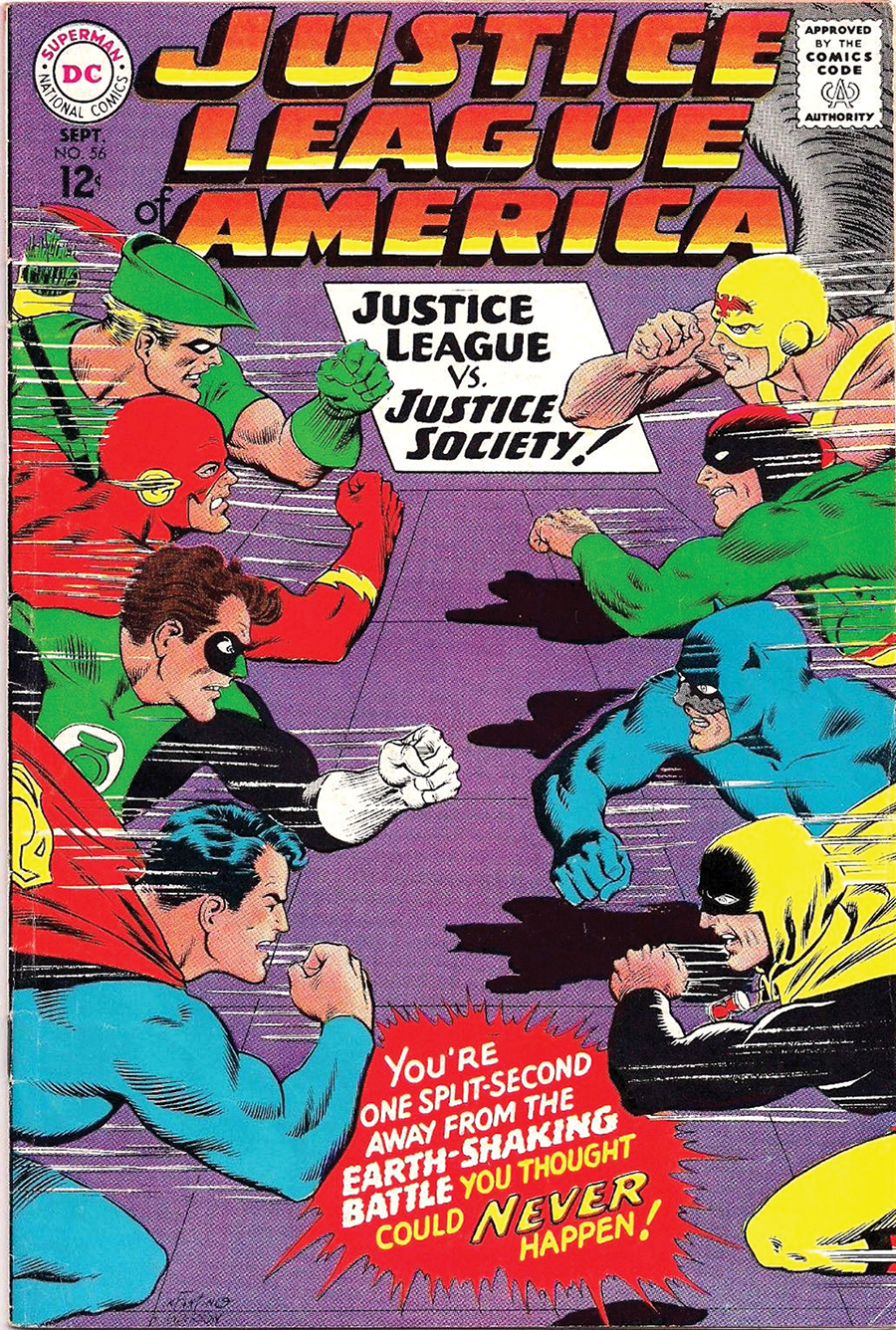

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

Wright’s not wrong. As a young comic book collector, one of my fav

Perhaps you know that saffron, the complex and costly spice, comes from the red stigmas of the autumn-blooming saffron crocus (C. sativus), not the snow crocuses you see now, bursting through the frozen earth. And yet, these winter-blooming beauties offer something of even greater value: the ineffable promise of spring.

Perhaps you know that saffron, the complex and costly spice, comes from the red stigmas of the autumn-blooming saffron crocus (C. sativus), not the snow crocuses you see now, bursting through the frozen earth. And yet, these winter-blooming beauties offer something of even greater value: the ineffable promise of spring.